WASHINGTON: The newly minted Commander of Space Command, Gen. John Raymond will oversee development of the geographic command’s first official ‘war plan’ for space. And where does space begin? It’s now defined by the Unified Command Plan as an “area of responsibility (AOR)” 100 kilometers above sea level to, well, infinity.

The new war plan, which must be approved by Defense Secretary Mark Esper, will be followed by updates to joint and service doctrine for space and counterspace operations, current and former military space officials say. (Yes, we just mentioned doctrine and there is more to come.)

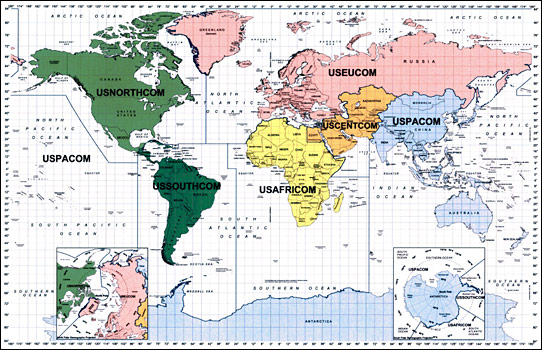

Up to now, space warfighting plans put together by Strategic Command (STRATCOM) under Gen. John Hyten– including Olympic Defender, the ops plan shared with allies — have had a not-quite-official status, according to a former Pentagon official. That’s because STRATCOM is a so-called ‘functional’ combatant command, with a support mission. The new and improved SPACECOM, as Raymond and other Air Force brass have been eager to point out, is now a ‘geographic’ command with responsibility for fighting anywhere above 100 kilometers.

“So just as we have recognized land, air, sea and cyber as vital warfighting domains, we will now treat space as an independent region overseen by a new unified, geographic combatant command,” President Donald Trump said at an Aug. 29 Rose Garden ceremony standing up SPACECOM.

What’s in a Name? Geographic vs Functional Combatant Commands

That distinction has garnered relatively little attention (it’s awfully wonky after all), but is actually important — as well as new. The previous iteration of SPACECOM (that lived from 1985 to 2002) was, like STRATCOM, a functional command that existed to provide support (both technical and qualified personnel) to those commands that actually lead battles — i.e. the geographic commands such as European Command (EUCOM) headquartered in Stuttgart, Germany.

“By creating a geographic rather than a functional command, you provide the commander with authority in his AOR that outweighs all the other COCOM’s authority in that AOR,” explained a former senior DoD official.

It also, as Lt. Gen. Joseph Guastella suggested in a Sept. 9 speech at the Mitchell Institute, means that SPACECOM can now lead a fight and be supported by the other commands.

“Specifically, with the May 2019 revision of the Unified Command Plan, the President assigned U.S. Space Command with the responsibilities of a Geographic Combatant Command with an area of responsibility (AOR) of 100 km above the Earth’s surface,” Lt. Col. Christina Hoggett, SPACECOM spokesperson, explained in an email. “This is acknowledgement of the fact that space is a physical, warfighting domain and that the Commander of U.S. Space Command will be responsible for ensuring freedom of action, protection and defense in that domain, just as terrestrial Geographic Combatant Commands, such as U.S. Indo-Pacific Command,” she said.

Besides SPACECOM, there are six more geographic combatant commands: EUCOM, Indo-Pacific Command, Central Command, Northern Command, Southern Command and Africa Command. There are four functional commands: STRATCOM, Cyber Command, Special Operations Command, and Transportation Command.

Of course, Raymond is unlikely to ask his staff to start over with a blank piece of paper, insiders say. Instead, he will probably tweak the plans and procedures already laid out by STRATCOM. Several sources said that, for example, Olympic Defender is expected to be revamped. Among other non-trivial decisions will be what responsibilities and authorities can be delegated to sub-commands, and/or to battlefield commanders.

But a new warfighting plan will be needed to sort out the relationships between SPACECOM and the combatant commands, said Brian Weeden, director of program planning at the Secure World Foundation and a former Air Force official with a space pedigree.

One big question, he said, “is the whole supporting command vs. supported command issue: in what situations will USSPACECOM be providing forces and support to other COCOMs, and in what situations will other COCOMs be providing forces and support to USSPACECOM?”

Weeden gave an example of a situation where SPACECOM would likely be “calling the shots on a course of action.” For example, if the US receives intelligence that Russia is prepping a strike against a US satellite, does SPACECOM task a drone or a B-21 bomber to take it out before it launches? Or, Weeden said, does Raymond choose instead to simply “maneuver the targeted satellite out of the way?” In that scenario, he explained, SPACECOM “would be the one calling the shots on the course of action and EUCOM would be supporting it with in-theater intel assets or strike packages.”

Rules of interaction also will need to be specified with regard to SPACECOM’s relationship to the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) during conflict, when NRO satellite operators will take orders from SPACECOM. Raymond mentioned the landmark NRO-SPACECOM agreement when speaking with reporters on Aug. 29, but he would not elaborate on the terms other than saying that NRO operations day-to-day would not be affected; instead, he said, the shift would happen during “higher states of conflict.”

A few more details dribbled out in the joint NRO-SPACECOM press release issued Friday about this year’s Schriever space wargame. “Recently we’ve reached an agreement with the NRO that, when a threat is imminent, (emphasis ours) the NRO will execute direction from U.S. Space Command to take protective and defensive actions to safeguard their space assets,” Raymond was quoted in the release.

“The ultimate purpose of this new agreement is to achieve unified action across the continuum of conflict,” the press release added. “Although this agreement does not constitute a formal command relationship nor does it transfer satellite control authority, it signifies the strong partnership between the NRO and U.S. Space Command.”

New Space Doctrine Needed

Current doctrine covering space operations also will have to change to characterize space as a warfighting domain, and reflect new chains of command. For those readers not quite as wonky as we (sadly) are, doctrine is aimed at guiding military forces in how to carry out policy and strategy decisions. It includes, for example, defining terms and concepts. The armed services have their own doctrine, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff staff put together joint doctrine that guides how the services work together and attempts to standardize terminology.

The latest version of the DoD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms defines joint doctrine as follows: “Joint doctrine enhances the operational effectiveness of the Armed Forces by providing official advice and standardized terminology on topics relevant to the employment of military forces. Although joint doctrine is neither policy nor strategy, it serves to make United States policy and strategy effective in the application of US military power.”

The central doctrinal document for space is Joint Doctrine 3-14, Space Operations, last updated in 2018. Perhaps one its most important functions is defining the types of space operations that can be undertaken and in what circumstances. For example, it explains the term “space control” as follows:

Space control employs OSC [offensive space control] and defensive space control (DSC) operations to ensure freedom of action in space and, when directed, defeat efforts to interfere with or attack US or allied space systems. Space control plans and capabilities use a broad range of response options to provide continued, sustainable use of space. Space control contributes to space deterrence by employing a variety of measures to assure the use of space, attribute enemy attacks, and consistent with the right to self-defense, target threat space capabilities.

The Air Force, which is the primary service involved in space activities, also has space doctrine, including an entire annex dedicated to counterspace actions called Counterspace Operations Doctrine. That document, among other things, also seeks to differentiate between offensive counterspace and defensive counterspace actions. It defines offensive operations as comprising the so-called 5Ds: deceive, disrupt, deny, degrade, and destroy the enemy’s space operations. Defense counterspace operations, on the other hand, “protect friendly space capabilities from attack, interference, and unintentional hazards, in order to preserveUS and friendly ability to exploit space for military advantage.”

One of the doctrinal changes to be made in the wake of SPACECOM’s creation will be to define not just passive defense operations, but also so-called ‘active defense’ ops, one source involved in the SPACECOM transition told me. What is meant by that ‘active defense’ in the space arena has long been, well, vague.

As Weeden noted: “It’s hard to tell if they really mean active defense (like reactive armor on tanks) or whether that’s just a euphemism for offense.”

The SPACECOM source tried to explain it this way: “Think of a cop defending civilians from an active shooter by using the bullets in their handgun,” quickly noting, however, that “it shouldn’t be assumed that an active defense capability will be destructive or irreversible when employed.” In addition, the source said, “unlike the active shooter, the cop doesn’t go on patrol with a goal of shooting his gun, or people for that matter.”

A number of senior Air Force officials, including Chief of Staff David Goldfein and former Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson have been signaling for a while now that the US military would be putting a stronger emphasis on offensive capabilities and operations — including unveiling new weapons.

When asked about this rhetorical shift, an Air Force spokesperson responded via email with the service’s typical boilerplate:

“The National Strategy for Space reaffirms that any harmful interference with or attack upon critical components of our space architecture will be met with a deliberate response at a time, place, manner, and domain of our choosing. The United States is strengthening options to deter potential adversaries from extending conflict into space and, if deterrence fails, to counter threats used by adversaries for hostile purposes.”

“US officials have been hinting for a while now, since the end of the Obama Administration, that the US has capabilities in space no one knows about which, if revealed, could serve as a deterrent,” Weeden said. “That may be some sort of super-secret offensive space capability that’s already deployed. But I think it’s more likely a latent capability that the US could operationalize on very short notice, like the recent test of a Tomahawk beyond INF treaty limits.” (The Intermediate Nuclear Forces treaty, from which the Trump Administration recently withdrew, limited the deployment of nuclear and conventional ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges of 500 to 5,500km.)

“That’s stuff I can’t talk about,” said one former Pentagon official, “but I will tell you there is a lot of talk that is seriously under represented in reality.”

The Edge of Space

Finally, one last wonky word regarding the ‘100km and above’ definition of space in SPACECOM’s AOR. Trump Administration officials involved are taking great pains to insist that this definition of space is simply aimed at delineating between SPACECOM’s AOR and those of the other geographical commands, which all are responsible for air domain operations in their region. It specifically is not meant to convey anything at all about the US position, officials say, in the long-running international scientific, and legal, debate about where airspace ends and space-space, so to speak, begins.

There is no internationally agreed legal definition of the boundary between air and space, despite more than 50 years of effort by the Legal Subcommittee of the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) in Vienna. Politically, the question is a hot button because under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty space belongs to everyone; whereas nations can claim sovereignty over airspace. This raises questions about whether nations have to get the approval to, for example, operate extremely high-flying drones or aerostats over their territory.

The lack of legal agreement is in part because there is no scientific agreement about the exact altitude where space begins, known to physicists as the Kármán line, after the Hungarian scientist Theodore von Kármán who first attempted to define where the atmosphere becomes too thin to support normal flight. Currently, the international organization charged with setting astronautical and aeronautical standards, the Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI), defines the Kármán line as 100km (62 miles) above sea level.

However, according to Harvard-Smithsonian astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell, there is a strong scientific argument for setting the line at 80km (50 miles, because satellites simply cannot operate below that altitude. If they dip below that level, they cannot continue to orbit but plummet down through the Earth’s atmosphere to a fiery death. McDowell will be presenting his work at recalculating the Kármán line (based on his review of von Kármán’s original math) at the October meeting of the International Astronomical Congress (IAC) here.

Further, he said, the SPACECOM use of 100km is a bit odd because currently, the Air Force gives out astronaut wings to pilots who fly above 80km. NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) use the same 80 km definition of space for their daily work.

So, a space law expert said, the 100km boundary is unlikely to be something the US pushes in other fora.