WASHINGTON: To meet Chinese and Russian threats, the Air Force needs to increase and modernize its combat air power, including more use of advanced, long-range drones and force multipliers such as its nascent battle management, command and control (BMC2) system for multi-domain operations, according to the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA).

In a study released today, “Five Priorities For The Air Force’s Future Combat Air Force,” CSBA charts a course for the service to recover by 2035 from its current conundrum: an aging fleet with diminished force capacity and capabilities, trapped in a budget that continues to force choices between fleet sustainment and modernization.

The new study builds off an earlier CSBA report, mandated by Congress in the 2018 National Defense Authorization Act, on the Air Force’s future ability to meet the goals of the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS) to ensure that the US military is able to take on peer power conflict. But CSBA now is arguing that the Air Force needs to build up a mixed manned/unmanned aircraft fleet and supporting infrastructure that can take on conflict with not just one peer power, but two at almost the same time.

While the study acknowledges that more money and people will be required, it does not offer cost estimates.

When pressed about the price tag, Mark Gunzinger, one of the study’s three authors, noted that the 2018 report of the congressionally mandated National Defense Strategy Commission recommended an overall increase in the DoD budget of 3 to 5 percent annually — about an $8 billion per annum increase for the Air Force.

The chances of that happening, he told me, “are slim.” However, he insisted that there is no way the service can meet 21st century threats without increased resources.

“The easy trades are gone. The hard trades are gone,” Gunziner told the audience at CSBA’s headquarters, noting that the Air Force cannot “retire” its way out of the current fleet challenges.

The Problem: Smaller Numbers of Older Aircraft

The study explains that both the service’s fighter and bomber fleets are becoming unsustainable due to a long history of budget cuts that CSBA suggests have been overly harsh in comparison to those borne by the Army and the Navy.

“Although the budgets and forces of all the Services were reduced, the Air Force absorbed the largest cuts as a percentage of its total obligational authority (TOA) from FY 1989 to the end of FY 2001,” the study asserts. Air Force TOA in its ‘blue’ budget decreased by 31.6 percent over this timeframe, compared to a 28.2 percent decrease for the Navy and 29.2 percent for the Army, it finds. The ‘blue budget,’ the study explains, “excludes pass-through funding for intelligence community programs, special operations forces programs, health care, and other funding requirements over which the Air Force has little control.”

In particular, the report finds, Air Force procurement funds were decimated during this time period. “This decrease includes a 52 percent drop in the Air Force’s total blue procurement budget,” it says.

Since then, the Air Force procurement budget has fluctuated, but sits at historically low levels today. For example, the study notes that the 2020 budget request included funds for 48 F-35As, a decrease from the 56 F-35As appropriated in each of the two previous fiscal years .

The upshot of the overall trend toward smaller procurement budgets, the study says, has been a much reduced fighter fleet facing increasingly lower readiness.

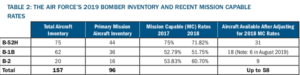

The bomber fleet has suffered in parallel. “The shortfall in the Air Force’s bomber force capacity has continued to grow over the last two decades, driven in part by force structure cuts, issues with force readiness, and a lack of modernization investment,” the study says.

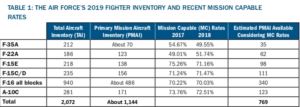

Based on readiness rates in 2018, the last year included in the study, CSBA estimates the service currently has about 769 primary mission fighters ready for action, and “up to” 58 bombers ready to take off. This is out of a total inventory of 2,072 fighters and 157 bombers. (The readiness numbers for the fighter fleet may be slightly higher now due to an increased readiness rate for the F-35 in 2019.)

CSBA says the average age of Air Force fighters has “reached an unprecedented high of about 28 years,” and the average age of the bombers hovers at around 45 years. As often has been bemoaned by Will Roper, the service’s top buyer, this has led to increased costs and personnel resources to maintain the fleet.

A Way Ahead: Modernization, New Capabilities

CSBA sets out five priorities:

Size the Combat Air Force (CAF) to simultaneously prevent China and Russia from succeeding in major acts of aggression.

The study boldly asserts that the Air Force’s aircraft fleet should be “sized and shaped” to reduce “the risk that a second great power aggressor could take advantage of a major U.S. military response to a conflict in another theater.” In particular, it argues, increasing the CAF’s “long-range penetrating strike capacity would help deny operational sanctuaries to China, Russia, and other aggressors.”

Procure more advanced stealth aircraft and fund survivability improvements for some CAF platforms.

“Next-generation stealth is the price of entry” for tomorrow’s warfare, Gunzinger said.

CSBA says that over the next two decades the Air Force “should accelerate the purchase of aircraft with next-generation stealth capabilities,” including B-21 bombers, F-35As, “a new multi-mission Penetrating Counterair/Penetrating Electronic Attack (PCA/PEA) aircraft,” and “penetrating” unmanned aerial vehicles carrying intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance payloads. The Air Force should also include “maintaining the survivability of the F-22 and procuring next-generation weapons, including a family of hypersonic weapons.”

Maintain the Air Force’s ability to generate combat power forward while dispersing to lower threat areas.

“Large scale Chinese Russia missile attacks on US theater airbases may not be the most significant threat to the CAF’s survivability,” Gunzinger said.

The future Air Force fleet should be “capable of supporting joint operations to deter or deny China or Russia the ability to achieve a fait accompli in these regions,” and at the same time be “able to generate strike sorties from bases located in areas that are at less risk of high-density missile attacks and generate counterair and other combat sorties from dispersed networks of closer in theater airbases.”

To enable this, DoD needs to “field higher capacity airbase defenses against large-scale air and missile attacks.” And the Air Force would require “additional resources and personnel end strength should it be given greater responsibility for the airbase defense mission.”

Develop and employ UAS for a wider set of missions in against more threats.

“The Air Force’s CAF lacks capacity to support high-end combat operations, sustain homeland defense, and meet other requirements of the 2018 National Defense Strategy simultaneously. This lack of capacity will likely persist well into the 2030s until new CAF capabilities can be delivered in scale,” the study finds. “To reduce the risk caused by this shortfall, the Air Force should develop new concepts for employing existing and future UAS [Unmanned Aerial Systems],” including MQ-9 Reapers and “lower-cost attritable systems.”

Gunzinger noted that examples of low-cost drones include the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Gremlins (small drones designed for swarming attacks), and Skyborg, a of the Kratos-built Valkyrie.

Such drones, the study says, “could team with manned stealth aircraft to conduct counterair, long-range standoff area surveillance, strikes, electronic warfare, and other combat operations in addition to performing ISR and light strike missions” — echoing the Air Force vision for a Next Generation Air Dominance family of systems.

Accelerate the development of Air Force next-generation force multipliers.

These include “next-generation hypersonic weapons, cruise missiles with counter-electronics high-powered microwave payloads capable of attacking multiple targets per weapon, advanced engines that will increase the range and mission endurance of CAF aircraft, and the datalinks needed to support multi-domain operations in contested environments.”

Replacing legacy Air Force BMC2 aircraft such as the E-3 AWACS and E-8 JSTARS with “joint all-domain BMC2 architectures would also increase the effectiveness and resiliency of the entire joint force in future operations,” the study says. This recommendation mirrors the Air Force’s ongoing effort to develop an Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS) for multi-domain C2.

ABMS, as Breaking Defense readers know, started out as a concept for replacing JSTARS and has morphed into a family of systems including hardware and software for creating what Roper says is essentially an “Internet of Things” for the service. The service also sees ABMS as the technology pillar of DoD’s emerging Joint All-Domain Command and Control concept, and is working to convince its sister services to commit to adopting future ABMS capabilities.