WASHINGTON: This fall, the Army’s Project Convergence wargames will host the Air Force, Navy, Marines, and Special Operations in a transcontinental scenario – one meant to replicate the vast distances of the Western Pacific and the technological challenges of a great power war.

The inaugural Project Convergence 2020 last fall tied in Marine F-35s with Army ground forces. Its somewhat ad hoc battle network transmitted targeting data from satellites in space to a ground HQ at Fort Lewis in Washington State, to artillery at Yuma Proving Grounds in Arizona, over 1,000 miles. But the upcoming PC21 will link Lewis and Yuma with White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico – and the 82nd Airborne Division’s HQ at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, more than twice as far.

But 2,000-plus miles is still only partway across the Pacific. It doesn’t quite get you from California to Hawaii. But it’s a decent test of the Army’s ability to operate along the strategically located First Island Chain, the series of islands running roughly 2,500 miles from Southeast Asia to Japan.

“Part of what we’re trying to replicate in some way is the battlefield geometry of the Indo-Pacific, [using] those similar geographical distances to stress these technologies,” said Col. Andre Abadie, who co-leads PC21 planning for Army Futures Command. “Clearly, it’s not the entire Indo-Pacific.”

Ultimately, Abadie told me, the goal would be to test the joint battle network over water in the actual Western Pacific. “Long distances over water do have some impact on waveforms and the way we communicate,” he said. But for now, it’s cheaper and easier to test it overland and entirely on US territory – and it still puts the often-immature technology through its paces in a realistic way.

It’s vital for the armed services to experiment – both individually and together – to see what technologies actually work before they try to lock down what a future Joint All Domain Command & Control network should be, Army Futures Command chief Gen. John Murray told us in a recent interview.

“We’re in the experimentation mode to understand what technology can and can’t do,” Murray said. The Army did a preliminary test of some 16 candidate technologies back in January, Communications Exercise (COMEX) 1 and will do a second COMEX this month with about 55 technologies. Some 1,300 contractor representatives participated in a recent online industry day, and more potential technologies will likely come from them.

“This is a journey to see what’s possible, what can we do with today’s technologies for a relatively minor cost,” Murray told us. “Project Convergence ’20 cost us about the same thing as one combat training center rotation”: about $23 million dollars. (Multiply that by about 20 CTC exercises a year).

If the Army can afford $23 million to get one brigade of the current force ready for today’s dangers, it can afford the same amount to help the entire future force get ready for tomorrow’s.

From F-35s to the “Desert Ship”

Project Convergence 2020 was conceived of as an Army exercise but the service brought in Marine F-35s as a target of opportunity because they were right next door at Yuma Marine Corps Air Station and are going to be key close air support and C2 data sources. This year, Murray and his officers have repeatedly said, the goal is to bring in all the other services from the start. The services first met to plan back in December and agreed the exercise would explore five “joint mission threads” and seven “use cases,” from offensive fires to logistics to air & missile defense.

Project Convergence 21 even has a “joint board of directors” with representatives from Marine Corps Capability Development Command, the Navy staff (sections N2/N6 and N9), and the Air Staff (A-3 and A-5), Abadie told me. They meet monthly, review the lab experiments and preliminary exercises laying the groundwork for PC21, and will make the final determination of what technologies are ready for inclusion in the exercise and which must wait.

There are three main joint contributions, Abadie told me:

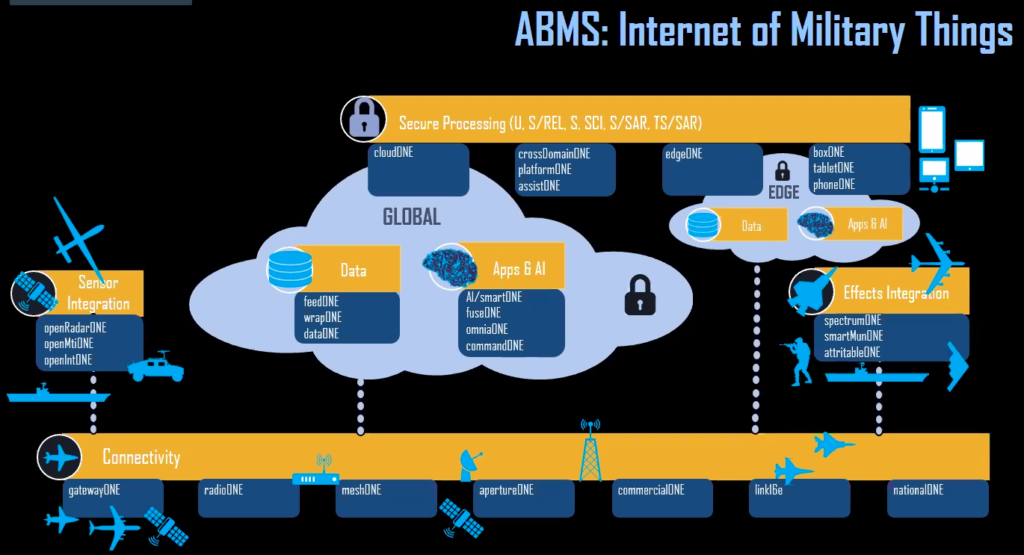

- The Air Force brings parts of its nascent Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS), a network of networks meant to link the whole joint force. ABMS components at work will include GatewayOne, which can translate between Air Force and Army electronics, and DataOne, a common data management system.

- The Navy has its Desert Ship, a test facility at White Sands that replicates the electronics and missile launchers of a destroyer’s Aegis anti-aircraft/missile defense system, including the Cooperative Engagement Capability (CEC) to share data with other ships and aircraft across the fleet.

- The Marines and, potentially, the Air Force will both bring F-35s, which will both spot targets and strike them. The Air Force’s fighters’ availability is still being worked out.

In addition, and in contrast to PC20 last fall, there’ll be operational ground units in PC21, not just soldiers operating specific prototypes and testbeds:

- Special Operations teams will provide human intelligence and ground reconnaissance, feeding the battle network a kind of data it can’t get from “technical means” like airborne sensors and AI.

- The 82nd Airborne Division will provide a heliborne assault force – equipped with the new IVAS targeting/data-sharing goggles – and a forward Tactical Command Post (TAC), linked back to its main headquarters at Fort Bragg.

- The Multi-Domain Task Force (MDTF) out of Fort Lewis is a three-year-old experimental unit designed specifically to coordinate far-flung, long-range operations. Its capabilities range from satellite ground stations to cyber/electronic warfare operators to HIMARS missile launchers.

In addition, like last year, prototype systems will take part. Weapons will range from the Extended Range Cannon Artillery (ERCA) howitzer and the Precision Strike Missile (PrSM). Robots will include Leader-Follower self-driving supply trucks and a host of unmanned systems, ground and air, for both reconnaissance and resupply. There’ll also be Army M1 Abrams heavy tanks, a modified Marine Light Armored Vehicle (LAV), and various experimental Robotic Combat Vehicles.

The Multi-Domain Task Force and Special Ops will take the lead during the “competition” phase of the exercise, simulating operations short of war, with MDTF collecting technical data on the situation and SOF collecting human. When the exercise moves into a simulated shooting war, it’ll place a heavy emphasis on both offensive strikes on the one hand and air & missile defense on the other.

The goal for the F-35s is to link them into the network as both “sensors” – spotting targets for offensive strikes and missile defense alike – and “shooters” – striking targets spotted by others.

“That’s part of the experiment,” he said. “Can the F-35 feed everything that’s in there? Can it feed the IBCS? Can it feed the Desert Ship, and then vice versa?”

Abadie wants to connect the F-35s, the Navy’s Aegis system on the Desert Ship, and the Army’s IBCS missile defense network, which didn’t participate in last year’s Project Convergence because it was undergoing a crucial Limited User Test. IBCS is still in development but will definitely play for at least part of PC21, Abadie told me.

Offensive strikes will draw from the same network, with missile defense systems being adapted to provide kinds of data they don’t normally collect to systems they don’t normally connect with, like the Army artillery fire control system, AFATDS.

Watching all of this play out will be observers from friendly foreign nations. The UK and potentially Australia will play an active part in next year’s Project Convergence. Just as PC21 brings in the joint services, PC22 aims to bring in the allies.

Correction: The original version of this article mistakenly referred to “Fort McChord.” The correct name of the installation, given in the version above, is Fort Lewis, which along with McChord Air Force Base forms Joint Base Lewis-McChord.