When Congress began pushing hard for some kind of Space Force the biggest concern lawmakers had was improving space acquisition. After the Space Force was created the Office of Secretary of Defense created a new space acquisition authority outside the control of the new service that was supposed to train and equip space warriors. The Space Development Agency has shown no signs of going away, though criticism of what appears to be its duplicative efforts and uncertain future persist. Instead, it may have come up with answers to some of the most difficult questions raised by the new American way of war, All Domain Operations. In this op-ed, Rebecca Grant tackles these thorny issues. Read on! The Editor.

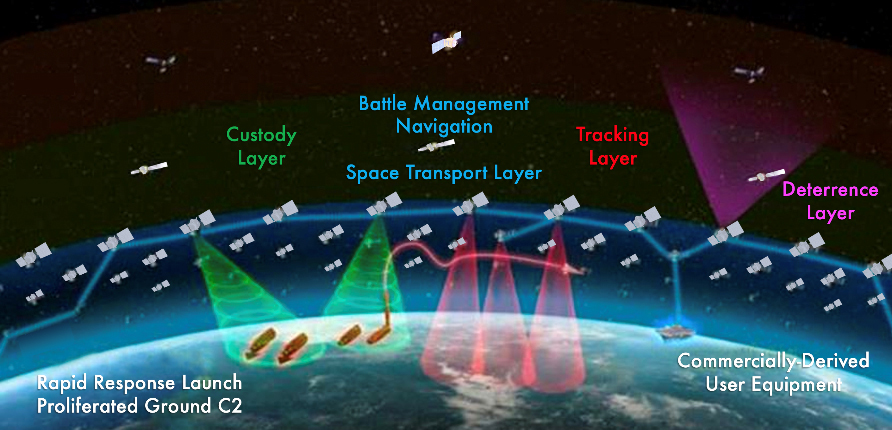

The Space Force faces an acid test as the effort to buy small satellites for the National Defense Space Architecture accelerates. The SDA constellation of up to 500 small satellites is destined one day to carry critical battle communications for the joint force.

“The satellites will be able to provide missile tracking data for hypersonic glide vehicles and the next generation of advanced missile threats,” Space Development Agency Director Derek Tournear said in February. Ultimately the architecture will take data “from multiple tracking systems, fuse those, calculate a fire control solution, and then the transport satellites will be able to send those data down directly to a weapons platform via a tactical data link, or some other means.”

The National Defense Space Architecture has to pull off what’s eluded warfighters: connecting sensors and shooters to face down those hypersonic missiles Putin brags about, plus anything China may dish out.

That’s a rather enormous mission. Its success rides on whether the new network can indeed fuse and prioritize data and feed it “directly to weapons and weapons platforms,” as SDA plans.

Moving crisp and accurate targeting data among the sensors and shooters is regarded as the key to victory in All Domain Operations. Done right, this could be the survivable, scalable JADC2 network the Department of the Air Force, Army and Navy are striving for.

It’s no secret that the current space-based system is vulnerable. The Air Force has taken steps toward building mesh networks in the air domain, using high-altitude platforms like the U-2 and Global Hawk, for example.

The National Defense Space Architecture goes one better, conceptualizing a space-borne mesh network that all domains can tap into. Mesh networks with many nodes can reroute data so enemies would have to destroy almost every node to take down the network completely. Some 500 satellites should ensure wartime performance.

It sounds good, but I have my doubts.

Not about the technology, per se. Multiple companies are already on contract or competing to provide the satellites and launch services. In June, four demo satellites will launch to test laser networking and optical links. These low-latency optical links can carry much more data between satellites on orbit. Of course, every component of the satellites, their laser terminals, software and ground links must be free from intrusive Chinese components or other supply chain factors that could create vulnerability.

Still, to my mind the hard part is structuring the data hand-off. Decisions will come up on how much data management takes place on the satellites and how they will use software-defined communications. Enter service politics.

To field the new network, Space Force Guardians must work with the Air Force and other services to set requirements for waveforms, data routing and even the various antennae ingesting data on platforms as diverse as stealth fighters and bombers, Navy ships, and Army land-based missiles and many more. Unmanned platforms will be in the mesh as well. Don’t forget all that must be shielded from cyber intrusion, too, although here again, a mesh is less vulnerable than a single node.

So far, progress on fielding JADC2 has not been rapid because the services have held back from committing to firm requirements. The airborne Air Force is still struggling to connect the platforms it already has. For that matter, the Army and Air Force are grappling with the doctrinal issue of who is supposed to defend bases.

The Space Force is at risk of making the same mistakes. This is the heart of All Domain Operations and it demands decisions. Will all that data feed to Link 16 or something else? How will secure waveforms be utilized? Who gets priority: the Army’s long-range missiles or Air Force fighters? When do they get priority? There’s a lot to sort out. For example, a March 18-23 global information dominance exercise used three tools named Cosmos, Gaia and Lattice to share data from strategic, operational global all domain awareness and tactical levels, with the tactical tool greatly increasing response options in “air-threat pairing to defensive assets,” according to NORTHCOM.

Translation: it was a gusher of data. Data fusion must get much, much better.

It’s nice to think AI programs will make the best choices based on tactical conditions. Actually, some commander will have to set priorities — mission goals — in advance. Faced with a spread of incoming cruise missiles, which target does the defense system protect: the US carrier, the airfield with F-35s, the Army missile battery supply point, or the allied government building? Or does the system wait to respond because Army Apache attack helicopters and their unmanned drones are operating in the airspace? Those are doctrinal clashes relevant to the Taiwan Strait, for example. The success or failure of the National Defense Space Architecture’s goals to provide missile tracking and feed data to weapons could depend on choices made before the shooting starts. Each service component might have different answers. Thus, the Guardians will have to help cut a path through those doctrine debates as they bring this powerful new capability online. Hundreds of satellites doing data fusion will be great only if the desired effects are clear.

While wargame debriefs often fail to mention it, there’s another dark secret here. The threat problem is triple what it was in the past. In the China scenarios, the air is thick with incoming missiles, planes, etc. The space-based battle communications network will have to handle both offensive and defensive operations. On top of all that, there will probably be lasers shooting at satellites.

Joint forces truly need a space-based net to gather and process data so commanders can tell friendly planes, guns and missiles where and when to hit targets, defend forces in the fight and keep satellites up.

Lives will be on the line. Remember Jan. 8, 2020, when Iran unleashed a heavy missile barrage on US forces and allies at Al Asad airbase, in Iraq. “The fire was just rolling over the bunkers, like 70 feet in the air,” one soldier told 60 Minutes a year later. Many Americans at the base took cover before the attack while others knew to ride it out, then prepare to fight.

Who warned them? A Space Force squadron in Colorado. US service members and allies will continue to depend on how well the Guardians build this new network.

Rebecca Grant, an independent defense analyst, earned her Ph.D. in international relations from the London School of Economics, then worked on the staff of the Secretary of the Air Force and Chief of Staff of the Air Force. She heads IRIS Independent Research, a defense consultancy.