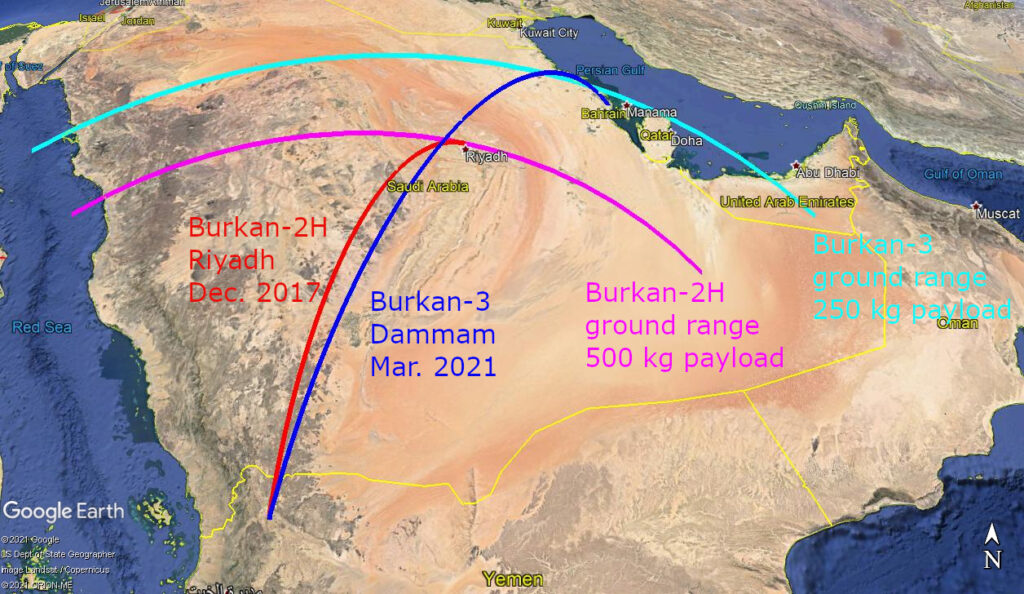

A new variant of the Houthi’s Burkan missile has a range of at least 1,200 km, putting almost all of Saudi Arabia within range of the Northern Yemeni rebels, posing a new threat to the kingdom.

Ansar Allah, as the Houthis are formally known, released footage in August 2019 of a new ballistic missile, called the Burkan-3 (or Borkan-3). They claimed that they had used it to attack Dammam but no such attack was confirmed at the time. Then, on March 7, a Houthi ballistic missile indeed did hit Dammam.

This is more than 1,200 km from their usual launching area and puts most of Saudi Arabia in range.

The obvious questions are, how did Ansar Allah achieve this and what does it mean for Saudi Arabia. Cast your eye on Iran. Based on an analysis of open-source images and video evidence, via computer simulations of missile trajectories, the Burkan-3 most likely is a variant of the Iranian Qiam, with longer propellant tanks and a smaller warhead mass. Combined with the notorious inaccuracy of most Scud variants, the reduction in payload required to achieve its longer range means that the Burkan-3 is essentially a terror weapon, not a precision guided weapon.

Since the 2015 Saudi intervention in the Yemeni Civil war, Ansar Allah has launched numerous ballistic missiles at Saudi Arabia. Prior to the civil war, the Yemeni military had North Korean Hwasong-5 and Hwasong-6 Scud missiles and, during the war, their Scud facilities in Sana’a fell under Houthi control. The UN Panel of Experts on Yemen has investigated wreckage of Houthi missiles used against Saudi Arabia: a Hwasong-6 flew 611 km in a May 2017 attack on Najran and Burkan-2H missiles were used in attacks on Yanbu on the 22nd of July and on Riyadh on the 4th of November 2017, over longer ranges.

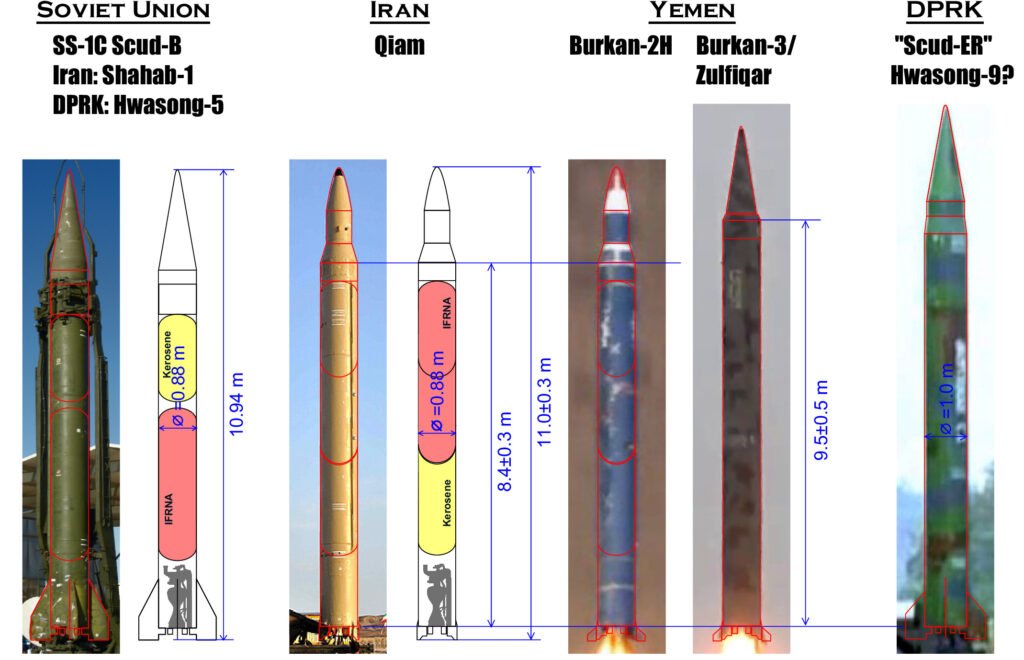

According to the panel’s January 2018 letter to the UN Security Council, the Burkan-2H has design features and dimensions that match the Iranian Qiam. These features include a short guidance section, longer propellant tanks with oxidizer tanks mounted above the fuel tank and with a common bulkhead, the absence of large stabilizing fins at the back and a so-called triconic re-entry vehicle. The letter also notes: ‘This means that they were almost certainly produced by the same manufacturer.’ Welds in the missile airframes suggest that the missiles were transported in separate sections, that were combined to form complete boosters locally in Yemen, to circumvent the UN arms embargo against Yemen.

Figure 1

Figure 1

(Original images are screenshots from Ansar Allah propaganda videos)

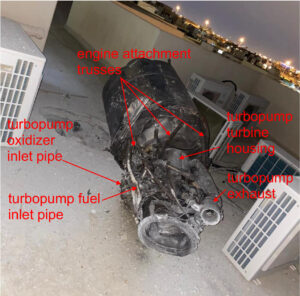

The newer Burkan-3, unveiled in August 2019 is somewhat different from the Burkan-2H. Its re-entry vehicle is conical, with a smaller diameter at its base than the missile. A short conical section mates it to the guidance section below. A February 2021 propaganda video shows a Houthi missile referred to as the Zulfiqar, used against Riyadh. This has a new name but looks identical to the Burkan-3. Its tail end landed on top of a house in Riyadh and although it is mangled, details of the engine installation and turbopump indicate that it is a Scud variant.

Figure 2, Zulfiqar engine on roof CREDIT: Saudi Press Agency

Figure 2, Zulfiqar engine on roof CREDIT: Saudi Press Agency

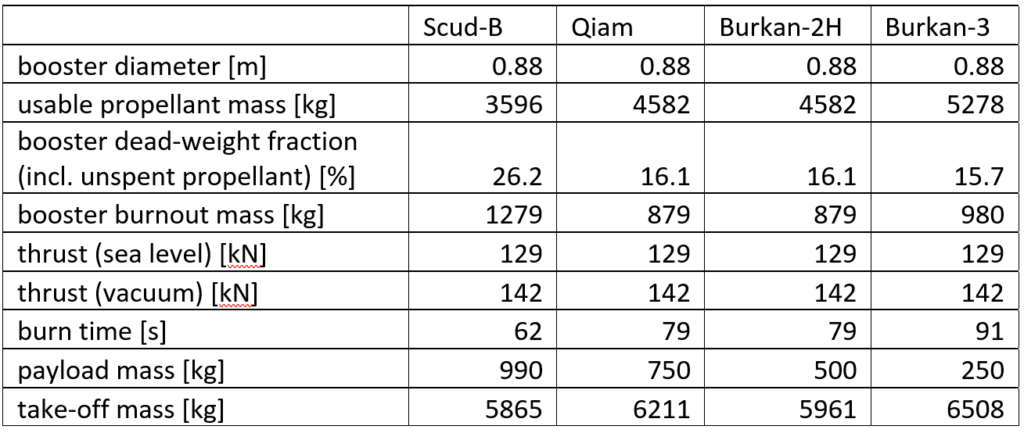

The range of the original Soviet Scud is 300 km and the Qiam’s range is 700-800 km, so the increased performance of the Burkan-3 is remarkable. To see how this is possible, its performance is assessed with computer simulations of missile trajectories. This is done using a medium-fidelity trajectory model, which was extensively validated using publicly available information of missile trajectories, from short ranges to ICBMs. The computer simulations require finding properties of the missile. Since all the images point towards the Burkan-3 being a Scud variant, it was modeled with the same engine thrust and propellant mass flow as a Scud.

The total missile propellant mass is estimated by reconstructing the size of the propellant tanks from photographs. Most Scud missiles have a 0.88 m diameter, and this is shared by the Qiam and Burkan-2H. If the Burkan-3 also has a 0.88 m diameter, it is considerably longer than the Qiam/ Burkan-2H. Since it has a shorter re-entry vehicle and a similarly short guidance section as the Qiam, its propellant tanks are longer. Their combined length is about 1.1 m larger, with a correspondingly larger propellant mass and longer burn time. North Korea has also developed an extended-range version of the Scud, unveiled in 2016, which is known as the Scud-ER or Hwasong-9. It is similar to the Burkan-3 in that the diameter of the base of its conical re-entry vehicle is smaller than the diameter of the missile. However, its body diameter is 1 m. It also has large tail fins, like older Scuds.

figure 3, Scud variants to scale

The final missile parameter required for the simulations is the take-off mass. This can be found by measuring the missile take-off acceleration from Iranian video footage of a launch of the Qiam and Ansar Allah footage of the launches of the Burkan-2H, in December 2017, and Burkan-3 in August 2019. The acceleration follows from the altitude as a function of time. For this the time is scaled using the video frame rate; the altitude (relative to the launch position) is scaled using the missile length. There is some uncertainty in the results due to uncertainty in the missile length and scatter in the data due to the low quality of the videos, but the measurements show that the Burkan-2H accelerates significantly faster than the Qiam. The take-off mass found from these measurements depends on the known thrust of a Scud engine, with a small correction for the launch altitude. Houthi missiles aimed at Riyadh are launched from a mountainous region north of Sana’a, at roughly 1.8 km above sea level and the reduced atmospheric pressure at this elevation increases the thrust.

The launch altitude for the Qiam is unknown, but assuming it was close to sea level, the slightly faster acceleration of the Burkan-2H is consistent with a 250 kg reduction in the take-off mass.

The trajectory simulations do not permit distinguishing between the payload and the empty mass of the missile. A measure for this is the so-called booster dead-weight fraction. It is the booster mass at burnout as a fraction of the booster mass on take-off.

The original Soviet Scud-B was built to be transported with propellant on board, so it had a large booster dead-weight fraction. The Qiam’s increased performance requires a lighter airframe, with a smaller booster dead-weight fraction than the Scud. The performance increase of the Burkan-2H over the Qiam could have been achieved by using an even lighter airframe, so with an even smaller dead-weight fraction, instead of less payload. However, structural considerations and the necessity to re-assemble or re-weld the missile make this rather unlikely. Its smaller take-off mass is most likely due to a payload reduction, from 750 kg to 500 kg. The acceleration measurements show that the Burkan-3 is significantly heavier than the Burkan-2H, but most of this is due to the larger propellant load. Lengthening the tanks while leaving most of the rest of the airframe unchanged gives the missile a slightly smaller dead-weight fraction than the Qiam and this results in an even smaller payload of only 250 kg.

Results of the computer simulations show that, with missile parameters based on the Scud, the Burkan-2H can indeed fly to Riyadh and the Burkan-3 to Dammam. The area of Saudi Arabia that is in reach of Houthi ballistic missiles now includes the relatively densely populated Saudi Gulf Coast, including Al Jubail, slightly north of Dammam and home to one of the largest petrochemical plants in the world. The computer models are completely consistent with all the measurements and with the demonstrated performance. Imagery of the Burkan-3 does not allow measuring its diameter, though.

However, if it were larger, like the DPRK extended range Scud, its take-off acceleration would be correspondingly larger too and the missile volume and performance would no longer be compatible with it being powered by a Scud engine. So, the Scud-ER cannot be the source of the Burkan-3 and, like the Burkan-2H, the Burkan-3 most likely is Iranian in origin too.

Obviously, reducing the warhead mass reduces its effectiveness as a weapon. Furthermore, Scud missiles are notoriously inaccurate. The circular error probable (CEP) of the original Scud-B is roughly 1 km at a 300 km range. This means that there is a 50 percent probability of the missile landing within 1 km from its intended aim point. It had a 990 kg warhead, including 545 kg of high explosive, which is similar to the WW2 V-2 missile, so data from missile attacks on London also gives an indication of the damage caused by a Scud. A V-2 warhead could destroy brick structures in a roughly 23 m radius and would leave buildings seriously damaged, but ‘habitable with repairs’ within a 46 m radius.

The Burkan-3’s warhead mass is roughly one quarter of the Scud’s. Since the damage radius scales with the explosive content cubed, this reduces its lethal radius by ~37 %. The Qiam reportedly is a bit more accurate than the Scud-B, with a CEP between 500 m and 1 km. Given its origin, the Burkan-3’s guidance system is likely identical and since its range is increased by roughly 60 % over the Qiam, its CEP will be roughly 60% larger too. So, due to the small payload, the area affected by a Burkan-3 impact is relatively small and, due to its poor accuracy, the probability of it destroying any particular target is effectively zero.

.Houthi missile attacks on Saudi Arabia are continuing and show that Saudi attempts at hunting down and destroying the launchers and the UN weapons embargo aimed at preventing missiles from being delivered to Yemen are not completely successful. The Burkan-3 dramatically increases the area Houthi missiles can reach, but it poses an almost negligible threat against any particular target. However, if used against a large densely populated urban area there is still a risk of damage and fatalities. As flown, this is essentially a terror weapon. Saudi Arabia claims that it can successfully defend its territory against most Houthi ballistic missile strikes, but their Patriot missile systems can only cover a limited area, so Saudi Arabia will need to choose whether to prioritize economic or military targets or the vulnerable civilian population.

Ralph Savelsberg, a member of the Breaking Defense Board of Contributors, is associate professor at the Netherlands Defence Academy in Den Helder, specializing in missile defense. This article does not reflect any official position or policy of the Government of the Netherlands. The author would like to thank James Kiessling for his valuable comments and suggestions.

Connecticut lawmakers to grill Army, Lockheed about job cuts at Sikorsky helicopter unit

“The Connecticut delegation has questions about why, with that [FY24] appropriation in hand, this happened,” said Rep. Joe Courtney, D-Conn.