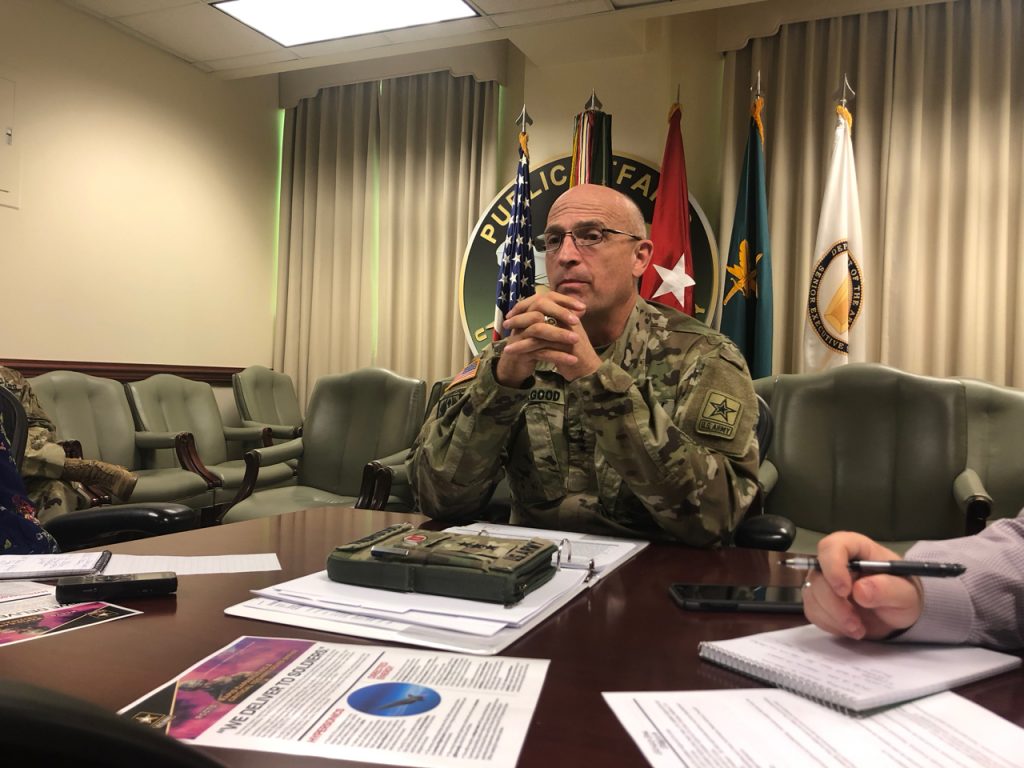

Lt. Gen. Neil Thurgood

WASHINGTON: Being transparent. Moving fast. Letting soldiers instead of engineers guide a weapon’s development. Tackle a “wicked hard problem” — like completing a hypersonic system — and get it done and fielded in five years.

For the last 20 years almost no one would expect to have heard those words — or seen that likely result — from an Army habitually ineffective and slow at designing and fielding weapons.

One of the prime drivers behind these changes is Lt. Gen. Neil Thurgood, the Army’s director for hypersonics, directed energy, space and rapid acquisition. His position was created to drive the Army forward in these key areas.

With China and Russia apparently ahead on hypersonics and some other key military capabilities, Thurgood said Wednesday at the Space and Missile Defense conference in Huntsville, Ala. that speed and effectiveness are of the essence.

“We had these great things we could do really fast in the 1940s and 50s. And then, somewhere across that time, we lost that capability in our nation. And I’m here today to tell you that our future is not our past,” Thurgood said. “It’s time to change our future, and we change our future by how we behave. And we can do hard things, we can be successful at wicked hard problems.”

The best example of the qualities of transparency and speed from the general’s speech is also arguably the hardest technical problem facing the US military: building an effective hypersonic weapon. The Army version is known as the Long Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW).

As work began on the LRHW program, Thurgood was given a stark and simple mandate.

“In 2019, the Secretary of the Army called me into his office with a gentleman named Bob Strider,” the deputy director of the Army’s Rapid Capabilities and Critical Technologies Office,” Thurgood said. “And he said, ‘Neil. I want you to deliver an offensive hypersonic weapon at the battery level and field it by FY 23. What are your questions?’ That’s the order. It wasn’t more complicated than that. I said, ‘hello sir. I got it. I’ll go figure something out.'”

And transparency? There were six companies key to the early stages of the hypersonics push. Here’s what happened at the first meeting they had with Thurgood.

“And I said, ‘I want to see you, I want you [industry] to present all of your financials and all of your schedules. Here in front of everybody.’ And you can imagine,” Thurgood said, “that conversation was pretty shocking. The first time didn’t go that great, quite frankly; it was a little concerning. And I said, ‘Look, how we’re going to do business is totally different. If you want to, if you want to behave like the past [then] your future will be your past. If you want your future to be different then don’t behave like we did in the past.”

And when the Army meets to discuss the program, Thurgood said: “So, they come to my program management review, they sit in my office, in my decision meetings. We are 100% transparent with our industry partners and we expect the same from them.”

The two sides share budget documents and more, he explained. “We are totally transparent with our budget documents. And they’re transparent. We have an integrated master schedule, integrated EVMS Earned Value Management System across six companies.”

Lockheed Martin concept art for its LRHW offering.

From the Army’s side, soldiers have been involved in the programs the general oversees from the very beginning.

“You don’t design it with engineers. You design it with soldier engineers at the very beginning of the problem set, not halfway through. We call that soldier-centered design,” he said.

More broadly, the Army’s Rapid Capabilities and Critical Technologies Office scours the defense and commercial industry, along with academia, for new ideas and tries to get them moving fast.

The office issues an annual white paper on major issues for the Army, in hopes of getting new ideas from outside the department. The first time they got 187 expressions of interest. The Army picked 32, who came in to do an oral presentation.

“We just did one in Atlanta with Georgia Tech. We paired with to Georgia Tech to do this,” Thurgood said. “And we selected nine companies out of the over 200 that replied to the request, and, and they’ll be under contract, and matter of fact, the first two of those will be under contract before the end of this month. That’s wicked fast from an idea that industry has.” Most of the companies are small non-traditional companies that have never worked with the government, but “they have these great ideas,” he said. “And so we’ve tried to create for our Army and for our nation a mechanism for you to get those good ideas to us.”

But is it working? Can the Army really deliver on a broader acquisition front?

“The jury is still out,” says Bill Greenwalt, a top defense acquisition experts who while a staffer on the Senate Armed Services Committee wrote many of the laws which now guide Thurgood.

“It is heartening to finally hear from someone in a senior leadership position in the Army that it is trying to innovate like America once did. Still, understanding our history is one thing— convincing the phalanx of historically illiterate naysayers from the appropriations committees on down is another,” Greenwalt wrote in an email. “The key factor to measure success will be whether Lt. Gen. Thurgood is given enough rope to succeed. Then, of course, he actually has to deliver in the limited time frame he will be in his position.”

Will Congress and the Army give him “enough funding and managerial flexibility to pick winners at scale? Will he truly innovate like we did in the 1950s, which means delivering operational capability in the two to five years that this nation once routinely used to do?

“Otherwise, he risks raising expectations and creating a new crop of small businesses who are all given door prizes for participation but no real path to compete against entrenched interests who, frankly, have better lobbyists than any new entrant (no matter how good their technology is) ever will.”