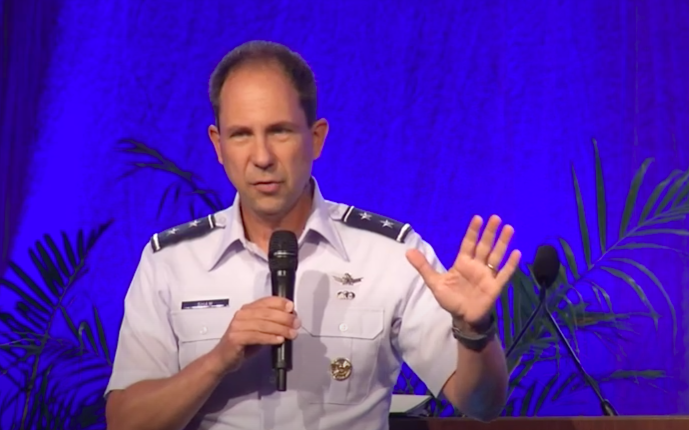

WASHINGTON: The key question for space operators in the near future will not be what systems should sport artificial intelligence or machine learning, but rather “what do you need humans for?” says Lt. Gen. John Shaw, deputy commander of Space Command.

“Depending on what … that satellite or that architecture is, what it’s doing, what its mission set is, what do I actually need humans to do? And I think we’ll find that that the vast majority of what a satellite will do on a day-in and day-out basis is going to be on its own,” he told the annual Small Satellite Conference today.

Shaw noted that for many years, the amount of autonomy “baked into” satellites and spacecraft has been growing, such as with NASA’s robotic missions on the Moon and Mars. Likewise, military satellites have been capable of ever-improving autonomous operations at least since the 1980s, he said, with capabilities to autonomously go into “some sort of safe mode” if something went wrong.

However, space operations today and tomorrow will required improvements. Or as Shaw put it, “We can’t do it old school.”

One of the challenges for future space operations, he explained, will be the need to use AI/ML to overcome the inherent time delays in satellite communications, brought on by the tyranny of physics. Radio frequency signals to and from satellites to controllers and users need time to travel, and the farther away, the greater the delay, or latency, in receiving them.

Reducing that time delay will be critical to rapidly connecting sensors to shooters, ensuring commanders all see the same real-time picture, and speeding up their reaction times — all capabilities foundational to the military’s new Joint Warfighting Concept. That need for connectivity will expand to commanders stationed in all domains — “including places other than on Earth in the future,” he said.

Shaw, like other DoD space leaders, has been advocating for more robust US military space operations in cislunar orbit — that is, in and around the Moon. And being able to provide space domain awareness about the cislunar environment is one mission for which robust AI/ML capabilities will be critical.

“You’re going to need some localized artificial intelligence or machine operation to do things and react to things happening in the local environment that would just take too long for humans to become aware of and react to,” Shaw said.

Further, he elaborated, the proliferation of large constellations of small satellites — primarily happening in Low Earth Orbit, or LEO, between roughly 100 and 2,000 kilometers above the Earth — will force a proliferation of AI/ML capabilities to manage them.

“We’re at [an] inflection point now,” Shaw said, “as we rapidly proliferate satellites in orbit, and the mission sets proliferate, and the capabilities expand.”

This will drive DoD space operators to try to better leverage autonomous capabilities being rapidly developed in the terrestrial sphere, such as “self-driving cars or airplanes that are more autonomous than they’ve ever been,” he said. “We’re gonna export that into space because we need it there. You’re not going to be able to have humans managing all of that.”

Indeed, Shaw issued a challenge to industry to actively work solutions to the question of bringing terrestrial advances in AI/ML to space operations. “As you see artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies developed in the terrestrial domains for terrestrial purposes, we should automatically be asking: ‘how does that now apply to space, how can we use that space?'”