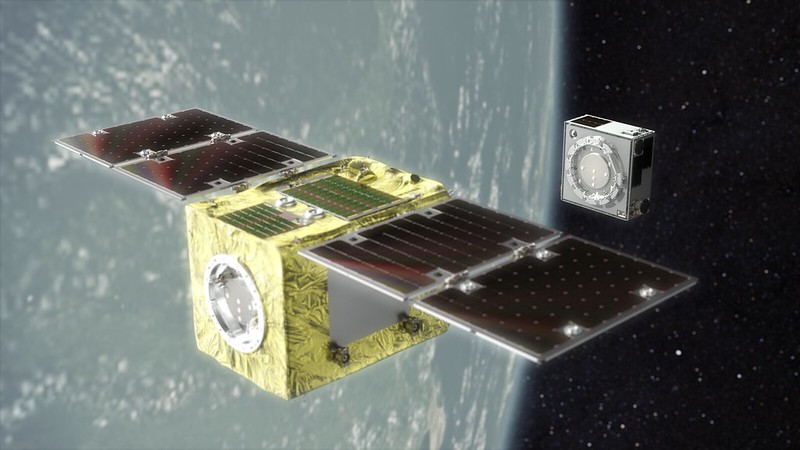

ELSA-d debris removal spacecraft. (Astroscale)

MAUI: There is a need for industry capabilities to clean up burgeoning amounts of space junk, and at the same time an urgency to getting a civil authority for managing orbital traffic up and running, according to Maj. Gen. DeAnna Burt, vice commander of Space Force Space Operations Command.

“We need to pick up debris — we need trash trucks. We need things to go make debris go away,” she told the Advanced Maui Optical and Space Surveillance Technologies Conference here on Wednesday. “That’s definitely a need, and I think there is a use case for industry to get after that as a service-based opportunity.”

The Defense Department currently tracks more than 27,000 objects in space, most of which is debris — such as defunct rocket bodies, according to NASA.

While Burt didn’t exactly say Space Force was planning on paying industry to develop debris removal technology, her reference to the concept of space trash collection as a service is suggestive — given that DoD has in recent months expressed interest in such a model for a number of different space capabilities, from satellite communications to intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) imagery and analysis.

That said, up to now, the Space Force has yet to move from interest to actually implementing a program or multiple programs to routinely buy space services of any type, much less for debris removal. So companies like Northrop Grumman’s SpaceLogistics and Astroscale have been focusing their internal investments on what are called “satellite servicing” missions, such as re-fueling or orbit correction or repairs as a new potential source of commercial income.

SpaceLogistics launched its first Mission Extension Vehicle-1 (MEV-1) robotic spacecraft to dock with, reposition and provide power to Intelsat IS-901 to re-boot its operations last February. It launched MEV-2 last August, and in April of this year docked with Intelsat IS-1002 to perform a similar life-extension mission for the dying sat.

“Our contracts for those are five year life extensions, and at the end of those services we will undock and move on to our next customers,” Joe Anderson, vice president of operations and business development at SpaceLogistics, told a panel on satellite services following Burt’s presentation.

SpaceLogistics’s website says the company’s “vision is to establish a fleet of commercial servicing vehicles in GEO that can address most any servicing need. Northrop Grumman continues to make deep investments in in-orbit servicing and is working closely with U.S. Government agencies to develop the next generation space logistics technologies.”

Japanese start-up Astroscale, which created a US arm focused on potential sat servicing sales to DoD, in March launched its End-of-Life Services by Astroscale demonstration (ELSA-d) mission. On Aug. 25, the company successfully tested its ability to capture a client spacecraft, release it, and re-dock using the a magnetic capture system, Mike Lindsay, the company’s chief technology officer, told the panel.

“A major challenge of debris removal, and on-orbit servicing in general, is docking with or capturing a client object; this test demonstration served as a successful validation of ELSA-d’s ability to dock with a client, such as a defunct satellite,” Astroscale’s website explains.

Unlike SpaceLogistics, which is under contract with Intelsat, Astroscale has used its own funds to undertake the demonstration.

Burt, who also commands Space Command’s Combined Force Space Component Command (CFSCC), told the AMOS audience that given the explosion of commercial satellites being put up — especially in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) where companies like SpaceX and OneWeb are expanding their megaconstellations practically every week — the specter of on-orbit collisions between satellites and/or pieces of space debris is looming ever larger.

“The pressure (on DoD) to ensure safety of flight and space, and space traffic management for the free and fair use for all has never been greater,” she said.

“The concern is: do you have a situation where you’re not managing your satellites properly and you have so many of them that you absolutely bump into each other?” she asked. “If you are not doing precisely station keeping, you then create debris and a ripple effect that affects the entire world.”

However, Burt explained, DoD doesn’t have authority to undertake true space traffic management. “We do space traffic awareness,” she said, in that the military provides information about where things are in space and what they are doing. It does not regulate or mandate what others do.

For that reason, she said, Space Force and Space Command leaders are eager to see the Commerce Department move more quickly to establish rules for managing space traffic — at least in the US.

“We as the Department of Defense look forward … to the Department of Commerce taking on this mission and standing up,” Burt said. “And why is that important to the military? This would allow for an important distinction about the separation of the civil to the military requirements that we have in our domain just like in every other domain. This will allow us Space Command to focus on space domain awareness, which could translate into battlespace awareness and how we would fight and win in a war that extends into space.”

The Commerce Department has come under both congressional and industry fire for what is widely seen as deliberate foot-dragging on creating both a new organization and a framework for developing such space traffic management practices, including setting up a service to relieve DoD of the burden of warning civil, commercial and foreign operators of potential on-orbit collisions. DoD officials too have expressed frustration that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) seems to be backtracking rather than moving forward on progress made toward that goal under the previous administration.

The Trump administration’s 2018 Space Policy Directive-3 (SPD-3) assigned the Office of Space Commerce (OSC) as the civil agency responsible for space traffic management (STM). That office falls under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service, which manages US weather satellites. The agency is also the parent body to the Office of Commercial Remote Sensing Regulatory Affairs (CRSRA) that regulates commercial remote sensing satellites.

The 2021 omnibus spending package passed by Congress last December granted OCS $10 million in funds to kick start a pilot program. That bill also allowed OCS and CRSRA to be merged into one entity, as stipulated in STP-3. The Biden administration’s fiscal 2022 budget request asked only for $10 million total for the new combined office, with no funds dedicated to setting up the new STM system. A 2020 study by the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) commissioned by Congress concurred with Commerce’s estimates at the time that between $57.4 million and $72.4 million would be needed just to buy commercial data and services through 2024.

“It’s going precisely nowhere,” one frustrated industry source lamented today, reflecting a widespread viewpoint by industry experts here. And anytime industry is begging for new rules and government action, the situation must indeed be dire.