The 2022 Reagan Defense Forum’s fourth panel, focusing on Ukraine, featured Sen. Joni Ernst (R-Iowa); Gregory J. Hayes, CEO and Chairman of Raytheon Technologies; Gen. Chance “Salty” Saltzman, Chief of Space Operations; and Christine Wormuth, Secretary of the Army. Lessons learned from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was a major point of discussion at the event. (Brendon Smith/Breaking Defense)

REAGAN NATIONAL DEFENSE FORUM — Over the past five years, the annual Reagan National Defense Forum has become something of a hub for the community of non-traditional defense firms to bask in the spotlight. Their presence has become ubiquitous, with executives in hoodies and flip flops hobnobbing next to military leadership, high-profile branding on the sponsorship rolls at the event and key spots on the forum’s many panels.

And yet, with the war in Ukraine prompting questions about the health and resilience of the defense industrial base, legacy defense primes this year seemed to steal back some of the limelight from the Silicon Valley-based tech startups.

“Our defense industrial base is unmatched, and we’ve got to keep it that way,” Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said during a wide-ranging Dec. 3 speech. “We’re working to strengthen our industrial base for the long haul. We’re also working closely with Congress to secure multi-year procurement authorities — and allow us to meet the needs of tomorrow.”

Austin’s comments were a sign of just how far the US defense establishment has come since the 2021 Reagan National Defense Forum, which occurred a day after multiple news outlets — citing US intelligence sources — broke the news on Russia’s plans to invade Ukraine in early 2022

Asked about those reports during last year’s forum, Austin said he was “very concerned” and that the United States would “remain committed to helping Ukraine defend its sovereign territory.” However, his speech focused on assuaging anxieties from defense startup execs, who worried that private capital could dry up unless the Pentagon began awarding production contracts.

Austin acknowledged those same concerns this year, saying that for many startups “securing the necessary capital to scale is hard, and sometimes impossible,” before promoting a new Pentagon office that will seek to link defense startups with private funding.

However, those comments made up only a short portion of a speech centered around strengthening deterrence against China and Russia, with big platforms made by major defense primes like the B-21 bomber and Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine called out by Austin as examples of American innovation.

RELATED: Top secret B-21 Raider stealth bomber finally revealed in high-powered ceremony

Trae Stephens, a cofounder of Anduril Industries, said one only has to look as far as the forum’s panel on innovation to see an example of how the Pentagon’s focus may be shifting. Instead of featuring the small startups and venture capitalists that had been a fixture in previous years, this year’s panel included two executives of huge firms that already do major business with the Pentagon: Boeing Defense CEO Ted Colbert and Karen Dahut, the chief executive for Google’s public sector business.

It’s far to early to know if this is a sign the prime contractors are clawing back some of the shine in Pentagon leader’s eyes that tech companies had taken over the last few years. But it may be a sign that the DC crowd is starting to have fatigue for the kinds of discussions that have become normal when discussing new defense entrants.

“I think people are just kind of tired of talking about [technology transition],” Stephens told Breaking Defense. “At the policy dinner I was at last night, one of the government people on it was like, ‘What do you guys think about how the contracting is working? I’ve heard all of the talking points about the valley of death and transition and blah, blah, blah. Are there any new things that you want to add to that conversation?’… No one feels like being beaten over the head about it.”

An Industry at ‘Battlefield Hospital Level’

The conflict in Ukraine and the COVID-19 pandemic have served as a wake-up call for the Defense Department about vulnerabilities in the defense industrial base, as well as the challenges the Pentagon could face if it was forced to majorly scale up weapons production in a war with Russia or China.

Over the first 10 months of the war, Ukraine has consumed as many Stinger anti-air missiles as Raytheon makes in 13 years, as well as many Javelin anti-tank missiles as Raytheon and Lockheed Martin produce in five years, Raytheon CEO Greg Hayes said at a Reagan forum panel.

“We spend a lot of money on some very exquisite large systems and we do not spend as much on the munitions necessary to support those,” Hayes said. “We have not had a priority on fulfilling the war reserves that we need to fight a long-term battle.”

Since the Cold War, the Defense Department has attempted to cut costs and become more efficient by minimizing redundancies within its acquisition system, said Bill LaPlante, the Pentagon’s undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment. “But one person’s efficiency is another person’s vulnerability,” he said during a panel at the forum.

Lockheed Martin CEO Jim Taiclet agreed that the defense industrial base is “overly vulnerable” to disruptive events, and although the twin crises of COVID and Ukraine have spurred some important lessons for the Pentagon, progress in beefing up industry is currently “a little bit at the battlefield hospital level.”

US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin delivered the keynote at this year’s Reagan National Defense Forum. Said Austin, “Our job is simple. And we don’t lose focus because of polls or politics. The U.S. military is here to fight and win our nation’s wars.” (Brendon Smith/Breaking Defense)

“You guys are fighting hard and you’re making progress. But as you said, the US defense industrial base is scoped for maximum efficiency in peacetime production rates,” he said. “Labor and supply shortages are still continuing through because we’ve been structured in this way.”

The industrial base “was also unable to rapidly scale and scale up quickly when the circumstances demanded that with Ukraine,” Taiclet said. “We should be applying concepts of anti-fragility to the whole industrial base. And by anti-fragility, I mean: When there are shocks to the system, they do not damage or stop the system from operating.”

The Pentagon has started making plans to transition certain critical munitions to a “more sustainable” long term production rates and is assessing the potential “chokepoints” for production. “It can be the workforce, it could be ball bearings, it could be batteries, it could be obsolescent parts, it could be micro electronics,” LaPlante said.

Once those vulnerabilities are found, they can be mitigated using the Defense Production Act or other mechanisms. However, those programs will require added investment to keep at a healthier rate of production.

“We have to get comfortable with the fact that production and getting to production is as important as any other part of the acquisition system,” LaPlante said. “And I would really want our folks that are innovators in the front end — which, we need you; we will not win without you — to also help us on the back end as well.”

Although changes aren’t occurring as quickly as either industry or the Pentagon would like, executives noted some progress. For instance, this summer Army acquisition czar Doug Bush was able to wrap up a contract for two National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (NASAMS) for Ukraine in 30 days — cutting down a 6 month process, Hayes said. The US Army delivered two NASAMS systems three weeks later.

“We have found ways to cut bureaucracy that I never thought was possible,” he said. “We can do this.”

‘We’ve Got To Get Scale’

While production of legacy weapons proved to be a more pressing problem, emerging tech still was a topic of conversation at the forum — although much of the discourse centered around the same concerns that attendees have repeated for years.

For multiple administrations, there has been more of a push for military leaders to reach out to newly established defense startups and nontraditional firms in Silicon Valley, as well as a surge in rapid prototyping and experiment efforts at the Defense Department, LaPlante said. “I think we’re at a point where we’ve got to get this into the mainstream, we’ve got to get scale.”

In a separate panel, Google’s Dahut agreed that it takes too long for small defense incubators to get relevant products to market. But since the establishment of the Defense Innovation Unit in 2015, there has been “significant” increase in focus on innovation in defense and aerospace, which suggests a positive role for the private investment and venture capital community in defense.

“That’s huge,” she said. “We need to get that capital working for us.”

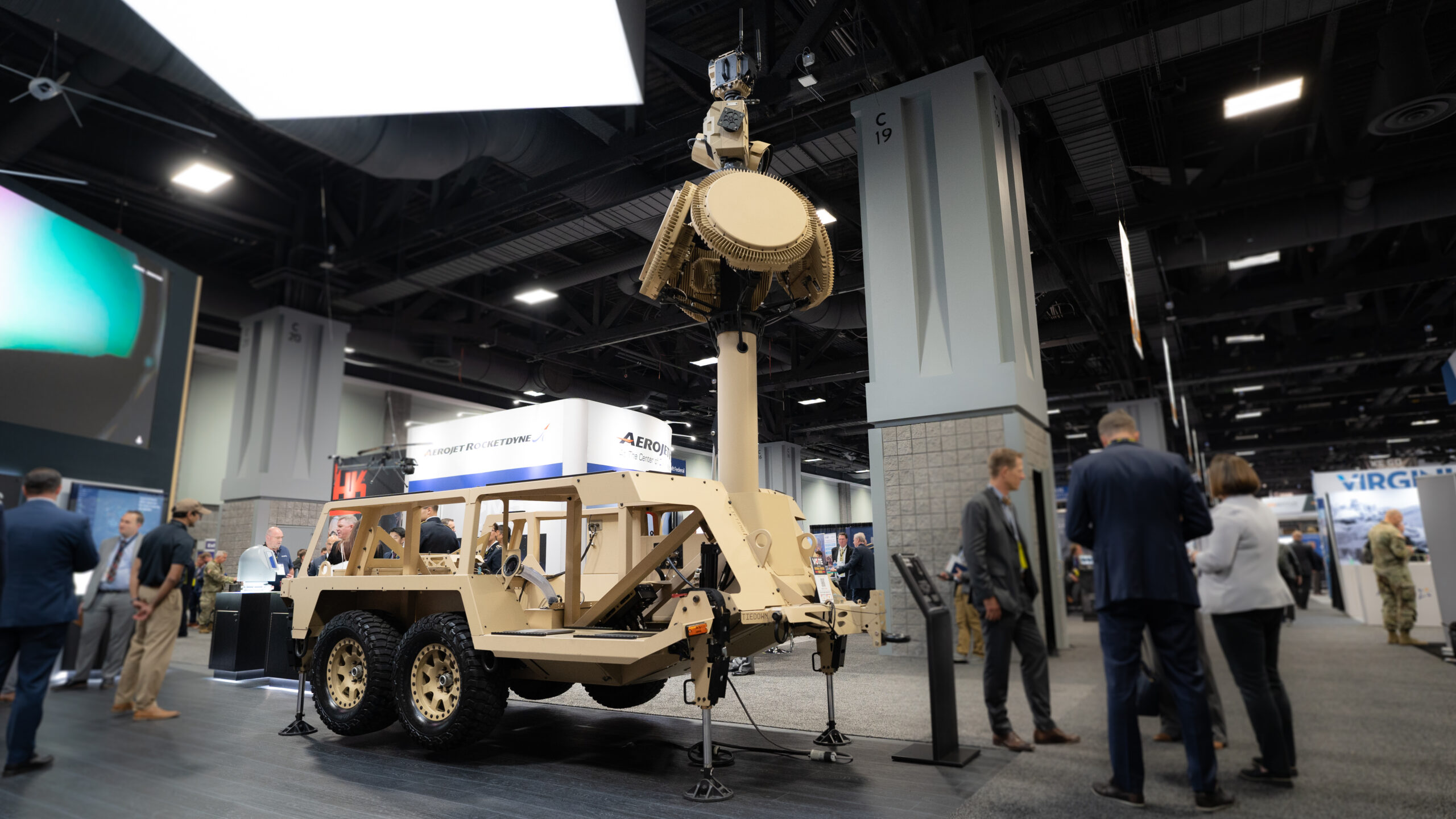

The defense start-up Anduril has expanded its footprint in the defense market in recent years. This product, the Mobile Sentry, “brings autonomous fixed site counter UAS and counter intrusion capabilities into a mobile form factor,” the company says. (Brendon Smith/Breaking Defense)

Anduril’s Stephens acknowledged that some progress has been made over the past year, pointing to the reauthorization in September of the Small Business Innovation Research program.

The Defense Department has also taken steps to catapult certain defense startups past the valley of death — including Anduril, which scored a contract from US Special Operations Command for counter drone systems worth up to $968 million this past January.

“That’s what leads venture investors to put more money into defense. They believe that they can make money in defense, which leads to other companies being started because they think that there’s a path to success. When we started, we were only able to do that because of Palantir and SpaceX,” Stephens said.

“It doesn’t feel like an ecosystem[-wide] culture shift. But I think the motions are leading to — on the edges —changes that have been a net positive,” he added.

But for more companies to get new technologies into production, they need to “debunk” the myth that technologies like AI aren’t proven just because they aren’t widely used by the US military, Dahut said.

“These are global scale proven technologies that technology companies use each and every day. They’re just not necessarily applied at scale by the department,” she said. “That’s where I think we need to focus our energy — applying these technologies to use cases rather than getting stuck in the R&D [research and development] pipeline around experimentation.”

In other words, “what we’ve got to do is actually pick some winners,” said Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. CQ Brown.

In interview with Breaking Defense, Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall indicated that the service may be ready to do just that. Kendall has laid out seven “operational imperatives ”— his top priority areas, which could see increased investment in leap-ahead capabilities. Over the past year, the Air Force has identified several emerging technologies in those areas that are ready to transition, Kendall said.

“Some of them came out of DARPA, others are out in the commercial world,” Kendall said. “We’re still in the development phase. It’s not production yet, it’s development. But when you buy software, it’s been produced, essentially, right? But there’s a question of how do you host it and how do you instantiate it, the processing and data storage, that sort of thing.”