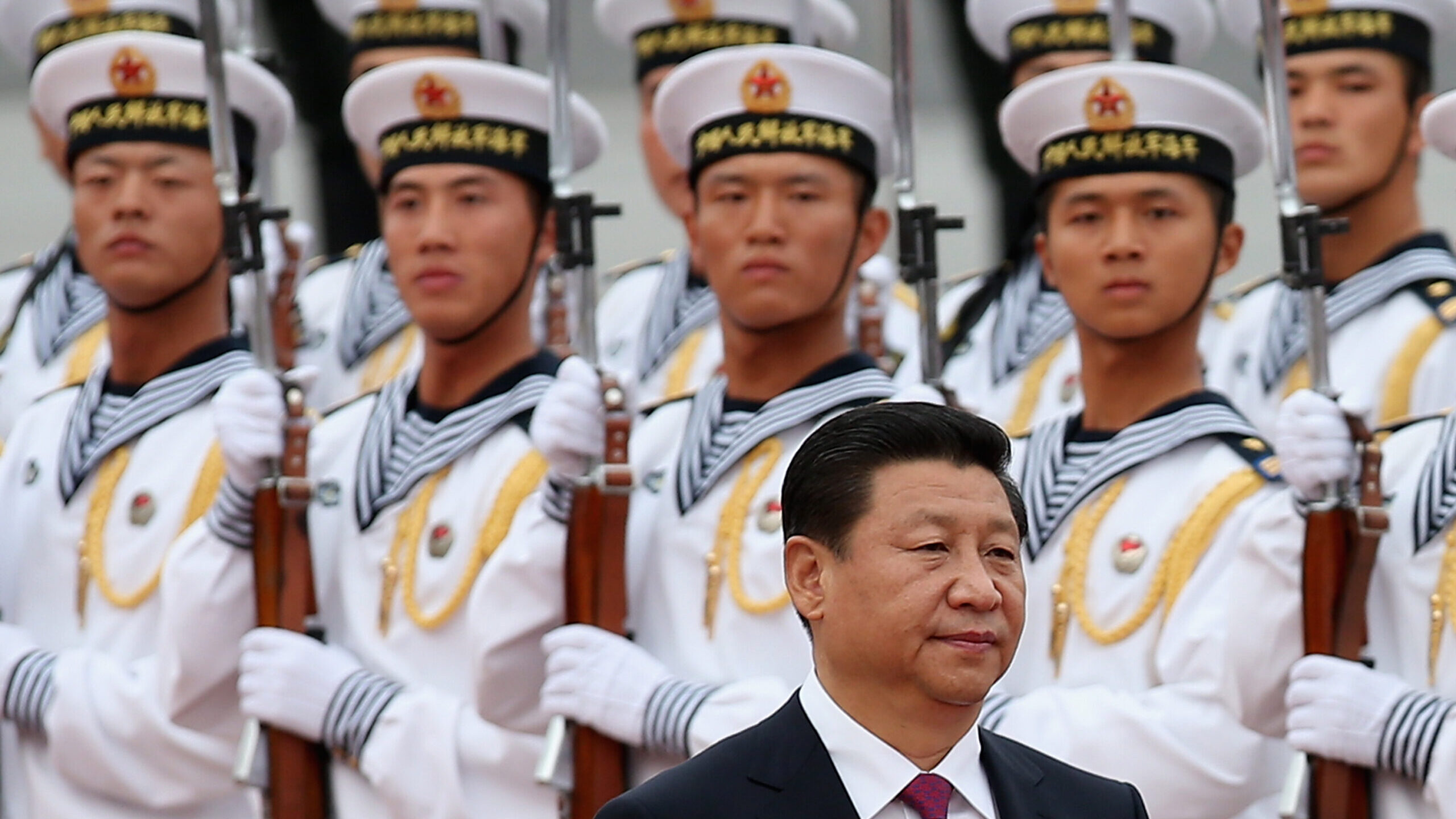

Chinese People’s Liberation Army navy soldiers of a guard of honor look at Chinese President Xi Jinping (Front) during a welcoming ceremony for King Hamad Bin Isa Al Khalifa of Bahrain on Sept. 16, 2013 in Beijing. (Photo by Feng Li/Getty Images)

SYDNEY — As China grapples with managing COVID-19 while reopening its faltering and debt-laden economy in 2023, US allies and partners will be making fundamental strategic decisions about their management of the rising state with a rapidly growing military. So with the new year comes a host of critical questions.

Will Manila invite the American military back to Subic Bay, the iconic naval base, and allow US troops to operate regularly from five other bases around the country?

The answer seems increasingly likely to be yes, with Chinese harassment of Philippine vessels and its persistent patrols in areas claimed by Manila helping the new government find clarity. The Subic Bay shipyard was purchased by the US-based private equity firm Cerberus Capital Management earlier in 2022. And there are persistent reports of efforts to bring the US Navy back to the vast port.

[This article is one of many in a series in which Breaking Defense reporters look back on the most significant (and entertaining) news stories of 2022 and look forward to what 2023 may hold.]

Will Australia forge a new strategic way ahead and commit to building a force more focused on long-range strike and reconnaissance, with beefed up force projection capabilities when its Defense Strategic Review is publicly revealed in March? Prime Minister Anthony Albanese made clear in a Dec. 19 interview with the Sydney Morning Herald that his country’s defense spending will almost certainly increase beyond the 2 percent increase pledged by the previous government.

INDOPACOM map of the Pacific. (INDOPACOM)

This looks like it may be the beginning of a new era in Australian defense, with plans to buy Abrams tanks and hundreds of Infantry Fighting Vehicles scaled back to free money for weapons designed to deter. He largely dismissed tanks and other heavy weapons for what he derisively said amounted to “defending western Queensland.”

In addition to its defense review, Australia will join the US and UK in unveiling the path ahead for the AUKUS nuclear-powered attack submarines, which Albanese staunchly defended in his interview with the SMH.

A crucial part of that will be whether and how the US Congress, the Pentagon and the State Department change the rules and laws governing the sharing of nuclear and other sensitive technology with Australia, and how the government then implements those changes. Congress will, of course, be fractured between a weak Republican majority in the House and a thin Democratic majority in the Senate, so making bold legal changes more difficult. And the White House will have to lead the federal government to the path it wants them to take to ensure Australia can build, deploy and maintain a small fleet of nuke boats.

Back in Asia, will Japan, which has just publicly committed to doubling its defense budget, actually buy new weapons to make its counterstrike capability real? When and at what scale? How will Australia and Japan’s remarkably close defense relationship coalesce? What will the recently declared intent by the US and Australia to invite Japan “to integrate into our force posture initiatives” on the island continent really mean? Perhaps Japanese troops, for instance, will begin to spend months exercising and training in Australia, alongside the US Marines and Air Force pilots.

What roles will Indonesia and Malaysia play in the complex dance between the United States, its allies and partners and China? Will they caution the major military powers against angering China while, at the same time, taking steps to bolster their own militaries and exercising with US allies and partners?

Perhaps most difficult to predict is how Russia will manage its Pacific defense forces, especially, as currently looks likely, its forces operating against Ukraine continue to degrade, taking heavy casualties and exhausting Moscow’s weapons stockpiles. Continued joint exercises with China seem likely, given how important China’s quiet and uncertain support for Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine has been to Moscow. Will Russia have to reorient some of its Pacific forces to the west as those killing Ukrainians die and are wounded, leaving units in need of rebuilding?

Underlying all of the above is the grim question, how will China react? Will Xi, weakened by the most brazen public criticism since the Tianamen Square revolt and his economic problems, come roaring back? Or will China spend the year regrouping and reconsidering its economic and defense policies?

Many of these questions may be answered in 2023, perhaps bringing with them an altered balance of power in the Pacific.