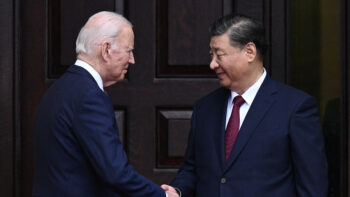

Fiji’s Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka (R) and New Zealand’s Prime Minister Chris Hipkins hold a joint press conference at Parliament in the Wellington on June 7, 2023. (Photo by MARTY MELVILLE/AFP via Getty Images)

AUCKLAND — In early June, Fijian Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka travelled to New Zealand, where he was treated as an honored guest. Weeks later, New Zealand’s defense minister, Andrew Little, arrived in Fiji and signed a Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) with the Fijian minister for home affairs and immigration.

This kind of relationship building may seem routine, but they represent something new for New Zealand — part of a larger, more serious regional outreach from Wellington. Begun in earnest in 2018 under former Prime Minister Jacinda Arden, who advocated a “Pacific Reset” as a foreign and defense policy priority, the outreach comes at a time when China is trying hard to sway Pacific Island leaders to its side, while the US and Australia seek to strengthen military ties in the region.

Anna Powles, a senior lecturer at the Centre for Defence and Security Studies in Massey University, told Breaking Defense that the broader effort is an attempt to create a coherent strategy for New Zealand when dealing with the southern pacific nations.

“This is really the first time that any New Zealand government has significantly re-calibrated its foreign policy towards the Pacific and frame it as their number one priority. There has been a shift in the way that New Zealand engages, notably through an indigenous-led foreign policy under [NZ minister for foreign affair and trade] Nanaia Mahata and a change in the tone of engagement initiatives,” Powles told Breaking Defense.

The funding for the Pacific Reset totals some NZ$714 million over four years. Ten new government positions were established in eight Pacific Island countries (Samoa, Tonga, Fiji, Vanuatu, PNG, Solomon Islands, Kiribati and Honolulu) and four in Tokyo, Beijing, Brussels and New York to coordinate development policy and partnerships for the Pacific region. And defense is very much a focus of the effort.

“While the Pacific has always been a priority, at times there has been a sense of apathy towards the region and a sense that there wasn’t as much effort put into relations in the Pacific,” from New Zealand, Powles added, “National security interests are very much at the core of the reset – that includes concerns around China’s ambitions and activism in the Pacific and certainly a degree of expectation and political pressure from partners such as the US and Australia that New Zealand will respond.”

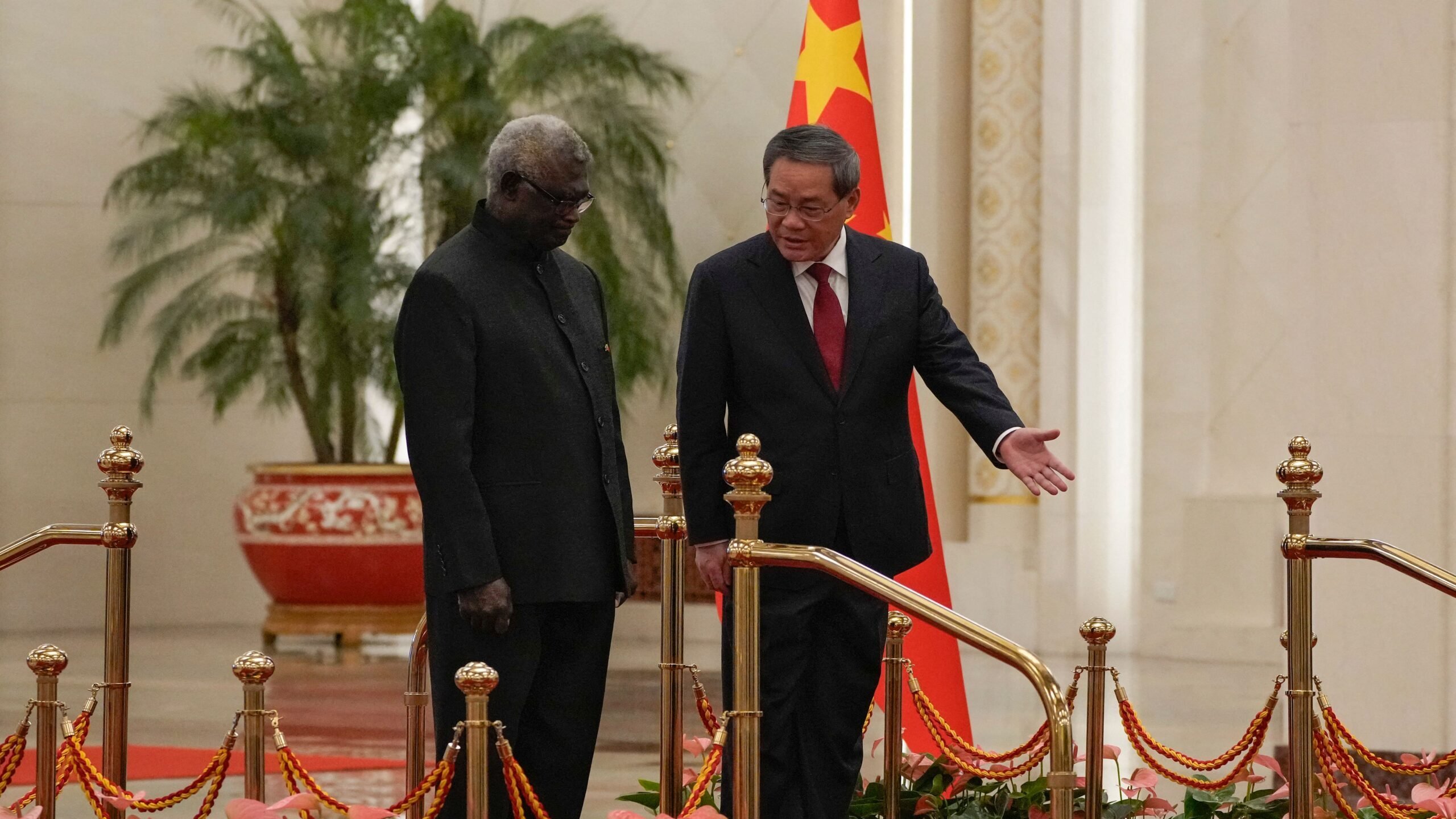

China’s Premier Li Qiang shows the way to Solomon Islands’ Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare after they observed their national anthems during a welcome ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on July 10, 2023. (Photo by ANDY WONG/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

Regional Defense Ties Strengthened In Recent Years

Fiji serves as something of a model for how Wellington can increase its regional ties, as it represents a dramatic turnaround in Fiji-New Zealand relations. A series of coup d’etats in 1987 saw the elected government of Fiji deposed and a Republic declared. These coups were led by current Prime Minister Rabuka, then a senior RFMF officer, and it removed Kiwi influence in the service that had just a few years earlier had appointed Brigadier Ian Thorpe as its Commander of Military Forces. Diplomatic relations soured to the point New Zealand and Australia called, unsuccessfully, for the UN to prevent RFMF serving as peacekeepers.

The SOFA built upon several years of work, starting with the 2020 New Zealand-Fiji Statement of Partnership 2022-2025 (also known as the Duavata Partnership) signed between Ardern and former Fijian PM Josaia Voreqe Bainimarama that called for “more regular exchanges.” The Chief of the NZ Army, Maj. Gen. John Boswell, visited Fiji in July 2022 with the NZ Officer Cadet School, and the NZ Army now supports recruit and Non-Commissioned Officer training in Fiji and has a strategic advisor based at the RFMF’s Blackrock Peacekeeping and HADR Camp in Nadi.

Little, the defense minister, told Breaking Defense that Fiji is a “significant defense relationship” for New Zealand. While the SOFA won’t lead to any specific additional exercises it does provide the framework helping “to facilitate, focus and frame our existing and future activities in Fiji.” He added that SOFA “expedites the administrative work required” for the New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF) and Republic of Fiji Military Force (RFMF) to engage, “enabling timely action when it is most needed, as in the case of a natural disaster.”

But Fiji is not alone. In April, New Zealand sent officials on a regional tour, the first such effort since 2019 thanks to COVID-19 protocols. Led by NZ deputy prime minister and associate foreign affairs (Pacific region) minister Carmel Sepuloni, it included visits to Fiji, the Solomon Islands and Tonga and focused on climate change, cost of living pressures, global inflation and heightened strategic competition.

In October 2022, Mahuta signed a new Statement of Partnership with Cook Islands Prime Minister Mark Brown that included further cooperation on security and climate change to support the aims of the Boe Declaration.

Also in June, at the invitation of the Samoan government, the Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN) Lake-class Inshore Patrol Vessel HMNZS Taupo completed a maritime patrol operation in the waters of Samoa’s Exclusive Economic Zone. The NZDF stated that three Samoan Maritime Police, who recently completed training with the Royal New Zealand Navy’s Maritime Training Team, two Samoan Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries officers and one Fisheries New Zealand Fishery Officer joined Taupo’s crew for the patrol.

And notably, in May Little and Mahuta announced that a NZDF deployment of 15 personnel in the Solomon Islands under the regionally-led Solomon Islands International Assistance Force (SIAF) would be extended by seven months through to the end of 2023. That comes after the signing of the China-Solomon Islands security pact in March 2022, which caught the US and its regional allies by surprise and has spurred a series of efforts in the region.

Overall, a spokesperson from the NZDF told Breaking Defense, there are also SOFA agreements in place with Australia and France (which governs New Caledonia). There are Visiting Forces Agreements or similar arrangements with the Cook Islands, Papua New Guinea, Tuvalu and Timor-Leste; and temporary stay agreements with Samoa and Tonga.

New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern speaks at the Lowy Institute, an Australian foreign policy think tank, on July 7 about New Zealand’s security challenges in the Pacific. (Peter Morris, Lowy Institute)

A Focus On Maritime Security

Given geography, it should be little surprise New Zealand’s defense relations with its neighbors come with a heavy maritime security focus.

New Zealand’s secretary of defense, the chief civil servant in the MoD, Andrew Bridgman visited the Solomon Islands in March, to observe the development of a new Maritime Security Strategy for the country.

Bridgman told Breaking Défense that the NZ team comprised two MoD officials, a Maritime NZ adviser, staff from the New Zealand High Commission and a NZDF representative. “New Zealand recently wrote its own maritime security strategy [Te Kaitiakitanga o Tangaroa] so it is in a position to share lessons learned with our Pacific neighbours,” he said.

Powles said that even though Australia has been leading with the development of the National Security Strategy and the delivery of two Guardian-class patrol boats to the Solomon Islands, it makes sense for New Zealand to take the lead assisting in this work given Wellington’s military is more closely tied to the smaller islands than that of Canberra.

Bridgman added that the MoD “will also support Fiji with the development of its Maritime Security Strategy. At this early stage of the process, the Ministry is exploring with Fiji’s Ministry of Home Affairs and Immigration what that support might look like.”

Meanwhile the MoD’s Mutual Assistance Programme (MAP) has been key in developing bilateral defense relations to support New Zealand’s foreign policy goals. It aims to improve the effectiveness of the Pacific Island partner countries, facilitate exchanges between forces and provide experience for NZDF units operating in a tropical climate. The NZDF offers courses in leadership, professional development and skills training.

The NZDF spokesperson said that under the MAP there are a total of 10 Technical Advisers (TAs) posted across the Pacific: two in Timor Leste, one in Papua New Guinea, two in Fiji, two in the Cook Islands, one in Tonga, one in Vanuatu and one in the Solomon Islands. While there have been technical advisors in Fiji in the past,” there are no plans for additional TAs to be posted to Fiji in the future,” the spokesperson said.

The TA in the PNG is a Colonel serving as Deputy Chief of Staff in the HQ of the PNGDF, while one of the TAs in Timor Leste is a Lieutenant Colonel acting as strategic adviser to the Chief of Staff in the HQ of the Timor Leste Defence Force. One of the TAs in the Cook Islands is a maritime surveillance advisor.

In addition, there “are Defence Advisers based in PNG, Tonga and Fiji. They are also accredited to Vanuatu and Solomon Islands (PNG), Samoa and Cook Islands (Tonga), and Tuvalu (Fiji). Additionally there are four TA Leadership Mentors supporting the NZDF’s Pacific Leader Development Programme – one each in PNG, Vanuatu, Tonga and Fiji. We also have a Major posted to the RFMF’s Joint Command Headquarters, Blackrock, Fiji.”

Challenges To Overcome

Looking ahead, Powles said that the challenge for New Zealand is how it can match its rhetoric and commitments to the Pacific.

There is a tension for New Zealand in how it manages its Pacific identity including with respect to issues such as opposition to the militarization of the region, she said. And the ability of the NZDF to carry out its key missions is in doubt — The NZDF has serious personnel retention issues and is struggling to provide key capabilities across the services.

“Does it have the capacity to live up to its responsibilities? There are real questions around this,” Powles said.

As early as the 2010 Defence White Paper there were calls for New Zealand to have the capacity to lead a response to a HADR crisis or other conflict in the Pacific on its own without Australian and support. “The NZDF must be equipped sufficiently such that it does not need to depend on partners and friends for basic forms of operating support,” the white paper stated, “There may be circumstances in the future where we would want the NZDF to lead an operation in the South Pacific or to operate there without needing to rely on others.”

Powles said: “Fast forward to 2023 and New Zealand does not have that capacity at all, not in any major significant way or that can be sustained.” This was evident when natural disasters occurred in New Zealand alongside corresponding ones in the Pacific. “New Zealand’s ability to respond to multiple disasters on the home front and in the region is reduced,” she said.

It is expected that the first elements of New Zealand’s new Defence Policy Review, due to be published soon, will address some of issues in the NZDF but there are no quick fixes and any solutions offered will only see results in the long-term.