WASHINGTON: Why has China, after a decade of “good neighbor” policies, engaged in high-profile high-seas standoffs with the Philippines and Japan? What is Beijing’s strategic purpose?

The most dovish analysts say that China is simply trying, albeit clumsily, to reassert what it considers its rights — its historical rights to territories China once controlled before Western imperialists and Japan stole them away during the “century of humiliation” between 1842 and 1945. The most hawkish analysts say that China is an unappeasable aggressor, like Imperial Japan in the 1930s or even Nazi Germany, and that any concessions by its neighbors or the US will encourage Beijing to grab for more. But both analyses have fatal flaws.

That’s my conclusion after watching retired Rear Admiral Michael McDevitt demolish dovish analyses this morning at the Wilson Center — and then asking him afterwards what he thought of the hawks (not much). [Click here for more from this event on China’s dangerous weakness]. In fact, McDevitt said, the painful truth is that Beijing may well be bumbling through these crises instead of possessing any strategy at all.

“I’m increasingly coming to the view that China’s reputation as a brilliant strategist is misplaced,” McDevitt told the audience. “They’re very tactical [and] focused on whatever is in the inbox…. Their reactions in many places seem designed to shoot themselves in the foot.” Policymakers in the People’s Republic, he said, don’t seem like worthy heirs to the ancient master strategist Sun Tzu.

McDevitt was speaking on a panel with two dovish analysts — Liselotte Odgaard, a Danish scholar, and Dennis Blasko, a former US Army attache in Beijing — who had just presented their paper on “China and Coexistence.” Odgaard and Blasko effectively blamed Japan for the crisis over the Senkaku Islands (called the Diaoyus in Chinese).

“Japan’s first priority is not stability,” Odgaard told the audience. “Stability requires you give a little, not just pursue your own position, and for Japan the most important thing is to maintain undisputed sovereignty over the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands.”

“China’s strategy does contribute to escalation and conflict,” Odgaard acknowledged, “[but] they probably hadn’t expected that….They’re following a standard behavior of Chinese foreign policy, relying on co-existence, and that usually works for China, [but] in this type of conflict about sovereignty, China lays claim to have historical rights” — in contrast to current international law based on “effective control” — “and pursues a standard of right and wrong conduct that no one else can subscribe to. That kind of creates the problem here.”

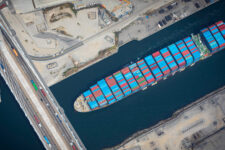

China is sending lightly armed, civilian, Coast Guard-type vessels (with some military backup) to assert its right to what it considers ancient Chinese territory “but the others perceive China’s actions as bullying and aggression,” she said. “So there is a signaling and communication problem.”

McDevitt’s dissection of this argument was a beautiful thing to watch, terribly polite and utterly devastating.

“The first thing that jumped out at me is the statement that peaceful coexistence is China’s grand strategy,” McDevitt said. “For those of us in Washington who are watching day in and day out….’peaceful cooexistence’ is not what comes tripping off the tongue.”

After reeling off a few other, more academic shortfalls in the paper — Odgaard was at one point scribbling notes like a grad student at her thesis defense — McDevitt added, “I was surprised that you reached the judgment on page seven that ‘China’s strategy of combining peaceful deterrence and active defense allows Beijing to signal non-aggressive intentions towards neighboring states.’ The signals are not being received that way.”

From the subsequent question-and-answer session, it seemed like the scholars and experts in the audience weren’t buying the “non-aggressive” interpretation either.

The hawks, however, have an enthusiastic choir to speak to. For an unnerving contrast to today’s dovish presentation, we just have to look back one week to the annual conference of the Air Force Association, where analyst Gordon Chang denounced China as a “classic aggressor” on Hitlerian lines and received, not skepticism, but enthusiasm and applause. (“He was great, just great,” I overhead one attendee saying afterwards).

Chinese forces have penetrated “deep” into Indian territory, Chang said, referring to April’s 19-kilometer incursion into an uninhabitable region in the Himalayas, and they have “seized” the Scarborough Shoal from the infuriated Philippines, a US treaty ally, by setting up cables and reportedly dumping concrete to create an artificial island on which to plant the Chinese flag. Now, he went on, “the Chinese are using forceful tactics to wrest the Senkakus” from Japan, with their long-term goal being the Ryukyu Islands and Okinawa, while “Washington and other capitals are doing their best to ignore what’s going on.”

This was the second year Chang was asked to speak at the AFA conference, and it’s easy to see why. “The sequestration is only going to last until the first big incident in the Asia-Pacific and then all these budgetary restrictions go out the window,” Chang told the enthusiastic audience of military officers and defense contractors. “The sequester may exist for another year or so… but the Chinese are going to end it,” with Beijing lashing out as its economy falls apart.

“I’m not saying that Xi Jinping is Hitler, because he’s obviously not Hitler,” Chang told me when I asked him after his talk, “but the dynamic is the same as 1939.”

“China is not the same as the Third Reich but the dynamic is the same, because both China today and the Third Reich then want territory under the control of others,” Chang said — and a limp response by the great democracies encouraged Berlin then and Beijing now to keep pushing right up to and over the brink of war.

“I think that’s over the top,” Rear Adm. McDevitt told me when I summarized Chang’s 1930s comparison for him. “It would be crazy to make that analogy.”

McDevitt agrees with Chang that China has plenty of economic, social, and political problems at home, but he sees those as sapping Beijing’s appetite for aggression rather than pushing it to lash out.

“China has so many internal problems, the last thing they’re trying to do is pick a fight externally that would actually lead to conflict,” the admiral said. “They’ve got a lot of things that they have to do.”

The Navy’s never-ending quest for 355 ships: 5 Navy stories from 2024

Ship counts were clearly on the mind of US Navy officials this year as they made numerous plays to bolster the fleet in novel ways.