Joan Johnson-Freese, a professor of national security at the Naval War College and a member of our Board of Contributors, is one of the world’s experts on international space cooperation. Decoding this stuff can get very complicated since many of those involved in international space issues toss around terms like COPUOS, IADC, apogee, LEO, GEO and conjunction and expect everyone to know what they’re talking about. Most people know about space debris because of the infamous Chinese anti-satellite test (most of them forget about the US shoot-down of its own satellite, US 193, which did NOT create debris). But few people really comprehend how dangerous it can be and how it can complicate the lives of the global scientific, commercial and national security communities. To learn more, read on. The Editor.

From the Cold War space race to the Apollo-Soyuz handshake in space, to holding China at arms length from International Space Station involvement, domestic politics have determined the tone and extent of our international space cooperation.

That is both disheartening and frightening. Disheartening because space is an inherently international domain which hosts assets providing and transmitting information key to personal, corporate and national well being in a globalized world, and it doesn’t work well without cooperation for the sustainable use of all. Frightening because of the willingness of some politicians to sacrifice space cooperation as a whipping boy for other issues, from personal religious views to disapproval regarding types of government or geostrategic land grabs, or to ignore the need for cooperation altogether.

The US is not the only country that politicizes space, with some countries still unwilling to engage in the kind of transparency needed as a prerequisite for space cooperation. But one organization has managed to rise above those politics and work productively toward space sustainability; the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC), set to hold its next meeting May 12 to 15 in Beijing. The question is whether its laudable work on maintaining space as a sustainable environment can clear inevitable future political hurdles.

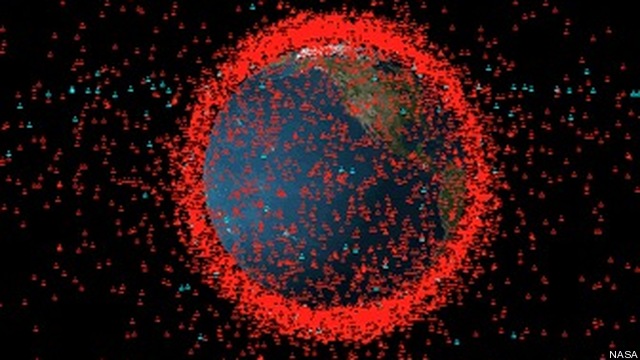

Space agencies have worked together since 1993 as an inter-governmental forum for the coordination of activities related to issues created by man-made and natural space debris, debris with the potential to wreck havoc on or destroy vital space assets. The primary purposes of the IADC are: the exchange of information on space debris research activities between member space agencies: facilitating opportunities for cooperation in space debris research; reviewing the progress of ongoing cooperative activities; and identifying debris mitigation options.

With 12 IADC members – the US, China, Russia, Canada, the UK, Italy, France, Germany, India, Japan, Ukraine, and the European Space Agency (ESA) — it might seem as though political bickering would be standard operating procedure, but that has not been the case.

A Steering Committee of agency representatives directs, by consensus, what studies the four IADC Working Groups will pursue about measurements (WG1), environment and database (WG2), protection (WG3) and mitigation (WG4). Philosophically, the key to the IADC’s success seems to be that it is, quite simply, in the vested interest in all members. It is in no country’s interest to have assets at risk from space debris. Key to this is releasing materials to the public only when all parties agree – thereby omitting or at least minimizing political potshots – and keeping everyone focused on confidence building through technical studies.

Agencies that join must be willing to share data relevant to the Working Groups’ studies and to work with them. One fruit of this cooperation: until recently national governments had few ways to predict when (or where) deorbiting debris – sometimes weighing tons – would hit Earth. These predictions have increased significantly, and are subject to far more confidence.

Proving once again that imitation still is the sincerest form of flattery, other space-related groups are now considering the IADC model.

An expert group chartered by the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) has been considering how best to track and warn of Near Earth Objects (NEOs) threatening to Earth. Chaired by Sergio Camacho, secretary general of the Mexican-based Regional Center for Space Science and Technology Education for Latin America and the Caribbean, the Action Group has recommended an IADC-like structure to create both a warning network and a Mission Planning Advisory Group. The idea is to, like the IADC, maximize results and minimize politics.

Admittedly, minimizing politics is not the same as removing politics. The 2007 IADC meeting was scheduled to be in Beijing, like the next one. That meeting was “postponed until further notice” after Beijing tested an Anti-Satellite (ASAT) weapon against one of its defunct satellites in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). The successful kinetic impact irresponsibly increased the amount of space debris greater than 10 centimeters in diameter by approximately 10 percent, making Beijing’s hosting of the IADC appear more than a bit hypocritical.

That ASAT test, however, and the 2009 collision of an operational Iridium satellite and a moribund Russian Kosmos satellite, raised international awareness regarding the space debris issue and the importance of IADC’s work. But the group very deliberately does not involve itself in policy. It produces voluntary guidelines for mitigation practices, shares best practices and data for use by its members. Still, what happens with that data becomes a political issue.

In February last year the IADC Steering Committee made a presentation to COPUOS on the Stability of the Future LEO Environment. Since 2005 some IADC members had independently studied the evolution of the far-term LEO satellite population under a variety of scenarios. The study aimed to answer the question: if serious mitigation efforts were undertaken, would the risks of space debris to space assets go down? In 2009, the IADC decided to assess the stability of the LEO space object population and the need to use Active Debris Removal (ADR) to stabilize the future LEO environment. In other words, did the world have to do more than watch carefully and act when needed? The IADC’s Environment and Data Bases working group did the assessment, with the principal participants in the study being Italy, ESA, India, Japan, the US and the UK.

Actually getting debris out of orbit — active debris removal — involves significant technical, financial, legal and security issues. Feasible debris removal techniques exist. Germany, Switzerland, the United States and several other countries have approved programs for the development and testing of capabilities that could be used for debris removal. To develop them to the point where they would be operationally useful to change the course of future space sustainability would be expensive, incurring costs that no one country currently seems willing or able to bear.

Also, since there are no salvage laws in space, each country owns its own space junk, making it impossible for another country to remove it without permission. Such permissions might be difficult to obtain due to security concerns. After all, grabbing a satellite and redirecting it could be a very useful tool of war. If Country X granted permission to Country Y to remove a piece of their space junk, but country Y “accidently” removed a different asset, that awould undoubtedly result in considerable consternation in Country X.

Ideally, any space debris removal program would be an international venture. But here’s the rub: who would trust another country to do the right thing in the right way? The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (DARPA) Phoenix program has shown great progress in the development of capabilities potentially useful in active space debris removal, and at a relatively low-cost. But who thinks the rest of the world would be willing to trust the United States to limit its activities to benignly removing space debris? And trust is the core issue.

The IADC has provided the global political community with empirical evidence that action needs to be taken to protect the sustainability of space. If only five large pieces of space junk were removed each year, the odds of a catastrophic event go down significantly. But the politics of fear, inertia and delay will likely prevail. Sadly, the most likely scenario to bring cooperation about: a debris-caused space catastrophe that leads to deaths on Earth,

When the IADC meets in May, it should be pleased with its success in working together. Its work is not done though. No one wants fingers pointing when the inevitable disaster occurs, and people ask “who let this happen.” What US politicians need to do is exert global leadership in assuring that the need to act is not ignored in favor of “politics as usual.”

How to tame your chatbot: secure containers, data diets, & more

The Defense Department wants to explore Large Language Models for everything from paperwork to war plans – without being misled by hallucinations or having sensitive information sucked up by commercial LLMs hungry for training data.