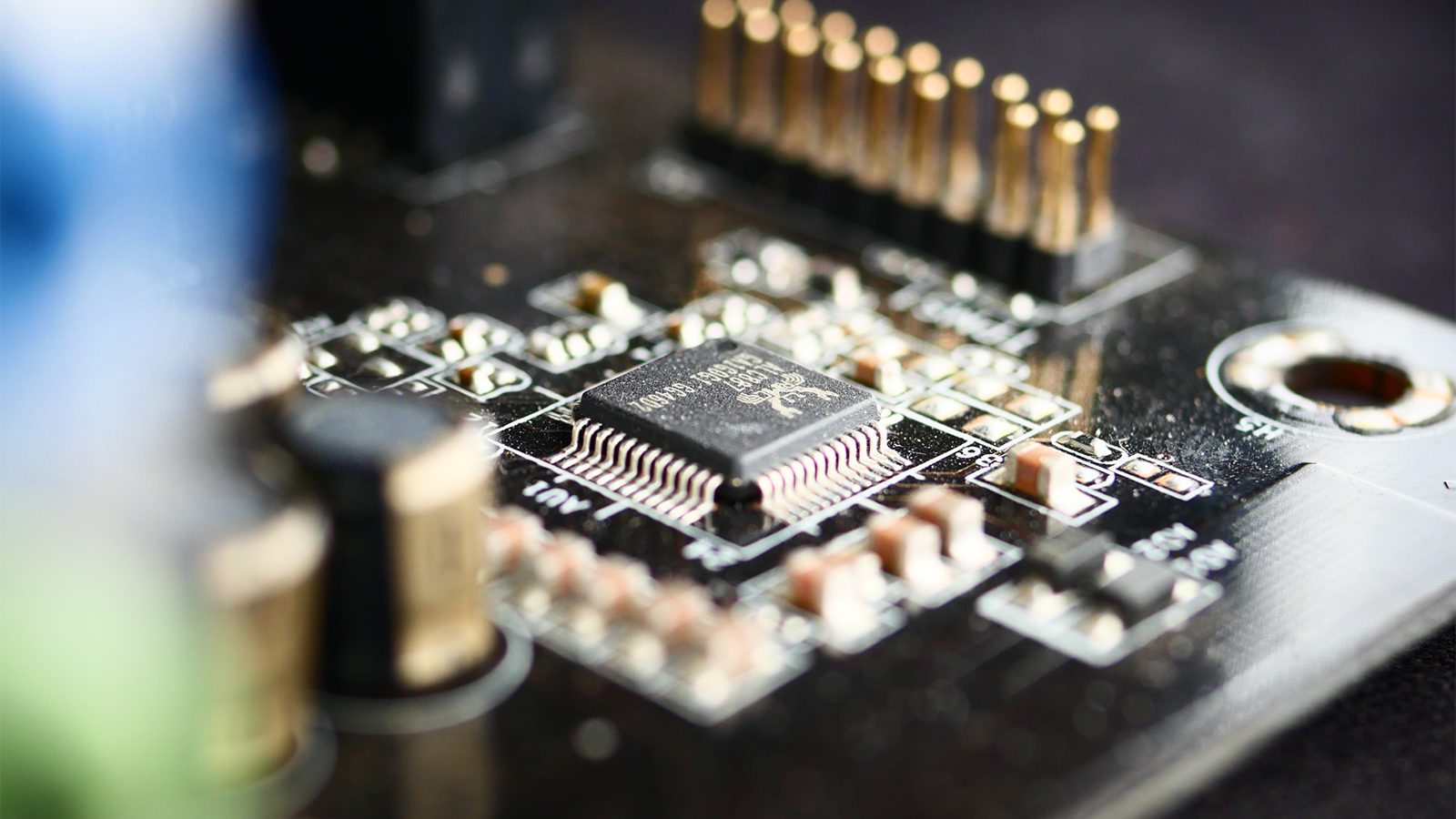

The US is investing heavily in microelectronics. (Photo by Rudolfs Klintsons via Pexels)

WASHINGTON — BAE Systems is working to transition the first set of multi-chip prototypes delivered under the Pentagon’s State of the Art Heterogeneous Integrated Packaging (SHIP) program into its electronic warfare weapons systems, as the US seeks to reshore its microelectronics capabilities and reduce reliance on foreign countries.

The prototypes were delivered six quarters ahead of schedule on Thursday at BAE’s facility in Falls Church, VA, marking the first tangible prototypes delivered under the SHIP program. The effort is being spearheaded by Heidi Shyu, under secretary of defense for research and engineering, who told reporters following the handoff that “the pendulum is swinging back to onshoring our own domestic capabilities.”

“We all know that microelectronics are ubiquitous and essential to the nation,” Shyu said during the ceremony. “Advanced microelectronics enable our troops with an advantage by making possible adaptive secure communications, electronic warfare, and long range weapon systems, just to name a few. To stay ahead, we need reliable access to secure microelectronics to meet our current and future systems requirements. The SHIP program understands the importance of getting this right.”

Shyu added that currently 90 percent of microelectronics design packaging is done in Asia, posing a supply chain risk to DoD. Microelectronics — used in virtually every advanced weapon system and deemed critical to the advancement of AI, hypersonics and other “disruptive” technologies — is one of the 14 critical technology subject areas that was laid out by Shyu in a memo obtained by Breaking Defense last year.

As part of the festivities, two tech partners handed off their work to BAE, who will serve as the final integrator of the chip onto a weapons system. Intel delivered its multi-chip package for SHIP’s digital aspect, while Qorvo delivered its multi-chip module for the program’s RF portion.

Tom Arseneault, CEO of BAE Systems, told reporters that the multi-chip technology, made of “chiplets” — tiny chips built for different technologies that come together in the packaging process — will allow mixing “radiofrequency type devices with standard digital type devices.” That mix of RF and digital is what makes up EW systems, he added.

“What’s represented here today is the ability to do what would normally take a much larger form factor card and turn it into a much smaller device,” Arseneault said. “And so you’re able to put this in places you might not have been before. It also allows you to put more in the volume of space that it would have taken up before, so that you can add more functionality in the same space. And so it’s a natural transition of modernization of the product.”

A key aspect that the SHIP program aims to address is lowering size, weight and power (SWAP) to “increase the capability of our chips,” Shyu said.

“Lowering SWAP allows the DoD to modernize our systems by fitting more functionalities into the system architecture,” she said. “Reducing the SWAP allows the devices to be integrated into edge computing processes so that we…can process things much faster edge edge namely at the user level. SWAP reductions will also provide significant…performance benefits and tactical advantages to service members, enabling the next generation of integrated sensors.

The delivery of the prototypes supports the mission of the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) and Science Act, which was passed last year, Shyu said, noting that the investment in the semiconductor manufacturing industry is “designed to bolster US competitiveness while strengthening the American supply chain and national security.” The CHIPS and Science Act designated $2 million specifically for military microelectronics.

While BAE is the first company to receive the prototypes for its EW systems, other companies, like Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman, will also get prototypes for use in their own weapons systems.

Shyu said that the “end goal for the SHIP program is to create a model for the DoD to sustain access to state-of-the-art microelectronics.”

“The DoD will continue to invest in programs to secure US microelectronics interests, and reverse the erosion of domestic innovation in supply chains, and to establish a strong foundation for the next generation of microelectronics technologies for our national security application while also sustaining current systems,” she said.

The SHIP program is one of several efforts underway at DoD to reshore its microelectronics capabilities: Last year, the Pentagon announced it would create “lab-to-fab” testing and prototyping hubs to build a network where microelectronics technologies could be matured faster.

Under that idea, Shyu created a “Microelectronics Commons” to provide broad access for the prototyping hubs through universities, start-ups, federally funded research and development centers and other facilities to transition microelectronics research. In DoD’s fiscal 2024 budget, the department is requesting $2.6 billion to address, in part, how to mitigate gaps in the “advanced packaging ecosystem” for microelectronics and continue the SHIP program.

Autonomy changes everything about combat engineering

Sending robotic vehicles into the breach saves lives by removing humans from one of the most dangerous places on the battlefield.