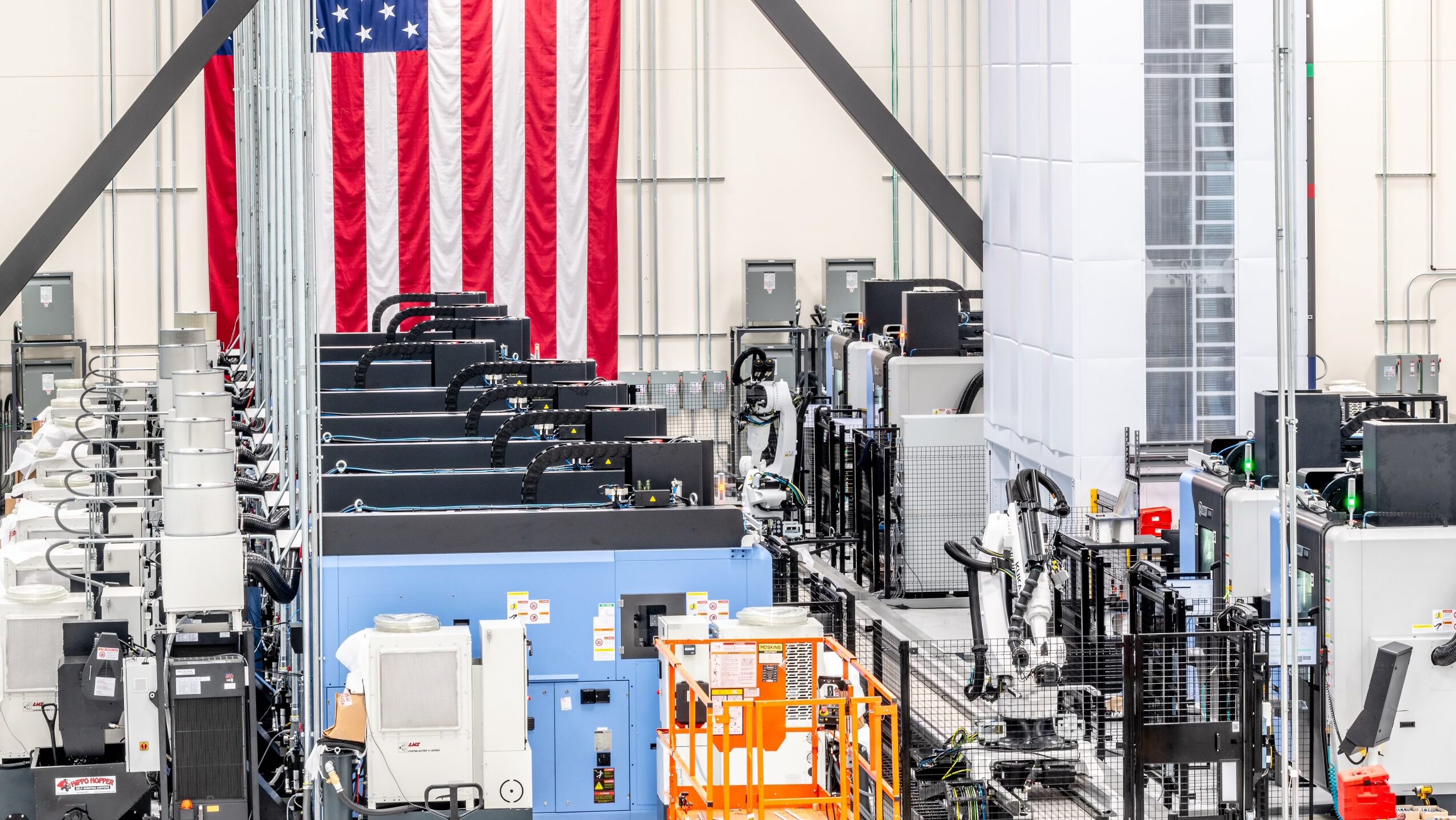

Advanced manufacturing machines on Hadrian’s production floor at its headquarters in Torrence, Calif. (Hadrian)

WASHINGTON — Almost every day, the founder and CEO of California-based manufacturing startup Hadrian says he gets a phone call from a defense prime struggling to figure out how to keep weapons production on track as one of its core suppliers goes out of business.

The request is always the same: “We need you to help us migrate that manufacturing to your facility so that we don’t delay the program,” said Hadrian founder and CEO Chris Power in an interview with Breaking Defense.

Aerospace and defense supply chains are on a slow path to recover from historic issues amid the COVID-19 pandemic, but businesses spanning from large first-tier suppliers to small machine shops are still feeling the pain of inflation, labor instability and lack of manufacturing capacity, with those obstacles even more acute for small mom-and-pop vendors, according to the Pentagon’s defense industrial strategy released earlier this year. Meanwhile, weapons producers are under pressure to ramp up production of key munitions and platforms as the conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza propel demand.

But that tension means opportunity for Hadrian, which is set to launch a second production facility next year as Power says the company is seeing explosive demand for parts it claims it can build 10 times faster than its competitors — and at half the cost — due to the high levels of automation and AI it has incorporated in its factories. Power declined to into detail about what kinds of parts it has already made in the defense world, but said they include components for major missile, fighter jet, space and shipbuilding programs — with defense making up about half of its current business.

Hadrian is still quite small compared to more-established defense startups, booking $3 million in revenue last year. (For comparison, Anduril reportedly told investors it had doubled revenue to $500 million in 2023, according to Tech Crunch.)

However, Power said Hadrian is quickly growing, with expected revenue on track to increase by 10 times in 2024. In February, the company announced it had secured $117 million in a Series B financing round, including an unspecified level of investment from RTX’s venture capital arm.

Power’s ambition doesn’t stop there. He told Breaking Defense he wants Hadrian to ramp up to the point where the company has “10 to 20 mega factories in all of the core manufacturing spaces in the country,” producing parts for “all the primes and neo-primes,” referring to both legacy defense contractors like Lockheed Martin and RTX as well as other defense tech startups like Anduril.

Power’s vision of Hadrian is a company that can produce parts so cheaply, quickly and efficiently that it can take over production and supply chain management for defense startups, allowing them to concentrate on developing new tech that Hadrian has the expertise to churn out at high rates.

“What I would hope to see over the next three years is: As you see many, many more companies that are small startups being awarded DoD contracts, there’s much less hesitancy for those companies that are winning prototyping awards to win real production contracts by partnering with companies like Hadrian that can get them from prototyping to production scale,” Power said.

Hadrian’s current factory — a 100,000-square-foot facility in Torrance, Calif., which the company moved to after growing out of its first factory in Hawthorne, Calif.— has enough capacity to produce the volumes of components expected for this year’s orders. A new factory “about two to three times the size” of the Torrance production line is expected to be launched in the fourth quarter of 2025, with a location to be decided by the end of March, Power said.

Hadrian has also begun scooping up other technology firms, announcing last week that it had acquired Datum Source, a software-as-a-service company that links customers to machine shops capable of making small batches of parts. Power said the deal positions Hadrian to work with defense and aerospace companies seeking to produce a couple prototypes before scaling up to full-rate production of parts that Hadrian can manufacture itself.

Manufacturing Robots Vs ‘One Guy Named Bob’

Hadrian was founded in 2020 after Power — who hails from Australia — observed the geopolitical competition between the United States and China and grew concerned about how America’s industrial strength measured up.

“If you look at the macroeconomics of great powers, usually what success comes down to is the industrial base. And I had this thesis that the industrial base had been in massive decline,” Power said. “So I moved to the US and spent a good six months learning everything that I could, and then quickly realized the situation was a lot worse than I had thought from the outside in.”

Specifically, Power said he toured production facilities and saw what he viewed as “a ton of fragmentation and a ton of weakness,” particularly regarding human capital. As one ventures deep into the aerospace and defense supply chain, Power said, it’s not uncommon to see small manufacturers that are reliant on the expertise of its blue-collar laborers, with few standard processes to guide new employees on how to produce components and no answer for how to retain knowledge as its aging workforce retires.

“You realize that the F-16 or F-35 ultimately rely on one guy named Bob knowing how to make the component in his head 10 layers deep in the supply chain,” he said. “That’s not a unique situation. It’s really 99 percent of the case — that’s what the industrial base is.”

“If you look at the types of factories China builds, they’re very automated. It’s not just low-cost labor, they’re far ahead of us on manufacturing technology in general,” he said.

RELATED: Should the US tame the ‘million monkeys’ of innovative startups in its tech race with China

To get the speed and efficiency Hadrian boasts, the company relies on a laundry list of artificial intelligence and robotics technologies that it says simplify the process of making parts and running a factory. For instance, one AI-enabled software turns legacy, hand-drawn blueprints and computer assisted drawings of parts into a digital blueprint, while other software helps automate factory scheduling and inspections. The production of a part is also highly automated, with advanced robotics allowing workers to run machines for “four times the uptime with 10 percent of the labor normally required,” Hadrian stated.

Power declined to comment on which defense companies it counts among its customers. He also declined to comment on whether Hadrian was working with the Pentagon on specific initiatives like the Defense Innovation Unit’s Blue Manufacturing effort, which seeks to establish a list of advanced manufacturing companies that can be tapped by the Defense Department to surge production if needed.

More generally, he said, Hadrian is “working with them on pretty large-scale initiatives that hopefully we can start talking about publicly in the next 15 months, on how do you do large-scale production manufacturing in the US?”

Defense startups — which Power said need Hadrian’s help transitioning from fabricating prototypes to manufacturing products en masse — make up the largest part of its client base, with orders from major defense primes and first-tier suppliers making up the second-largest portion.

But that doesn’t mean that defense primes are only using Hadrian as a stopgap — a position that could leave Hadrian vulnerable if surge demand for weapons decreases as conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza draw on.

“Eighty percent of our revenue is long term, three-to-seven-year production contracts,” Power said.

The defense and aerospace industry is a notoriously strict manufacturing apparatus, where parts must sometimes meet measurement standards within fractions of millimeters to ensure the safety of military operators or airplane passengers. But despite the emphasis on quality and compliance, Power said that most legacy defense and aerospace companies are willing to take a chance on Hadrian, in part because the current state of the supply chain is so exposed to unpredictability.

“It sounds unbelievable,” he said. But “usually, once people have experienced what we can do once or twice, that’s when we start getting awarded these large production contracts very quickly.”

![RS179755_PMCS2620-FCAS-JPN-5A[1x1]](https://breakingdefense.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2024/12/RS179755_PMCS2620-FCAS-JPN-5A1x1-e1734095138256-225x150.png)