WASHINGTON — The Defense Department’s research & engineering arm is about to announce over a quarter billion in CHIPS Act funds to build prototypes of advanced electronics, a key capability the US has almost entirely offshored, the Pentagon’s principal director for microelectronics said Wednesday.

“Very soon we plan to announce project awards worth $280 million,” said Devanand “Dev” Shenoy, the principal director for microelectronics for Pentagon CTO Heidi Shyu.

This year’s grants build on a previous round announced last September, which split $240 million amongst eight newly created regional hubs across seven states. (Specifically, Arizona, Indiana, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, Ohio and two in California). That funding jumpstarted a public-private coalition called the Microelectronics Commons, whose membership has since grown to about 1,200 universities, private companies and other organizations from 35 different states.

Those 2023 grants funded construction of the sophisticated infrastructure required to build cutting-edge prototypes, Shenoy told the INSA Intelligence & National Security Summit here. Now, he went on, the 2024 round will fund actual fabrication of prototypes using that infrastructure.

“When you think about the ecosystem for microelectronics, we’ve for many decades relied on other countries for doing a lot of the prototyping,” Shenoy told the conference. “We’re trying to address … the ‘lab to fab’ gap.”

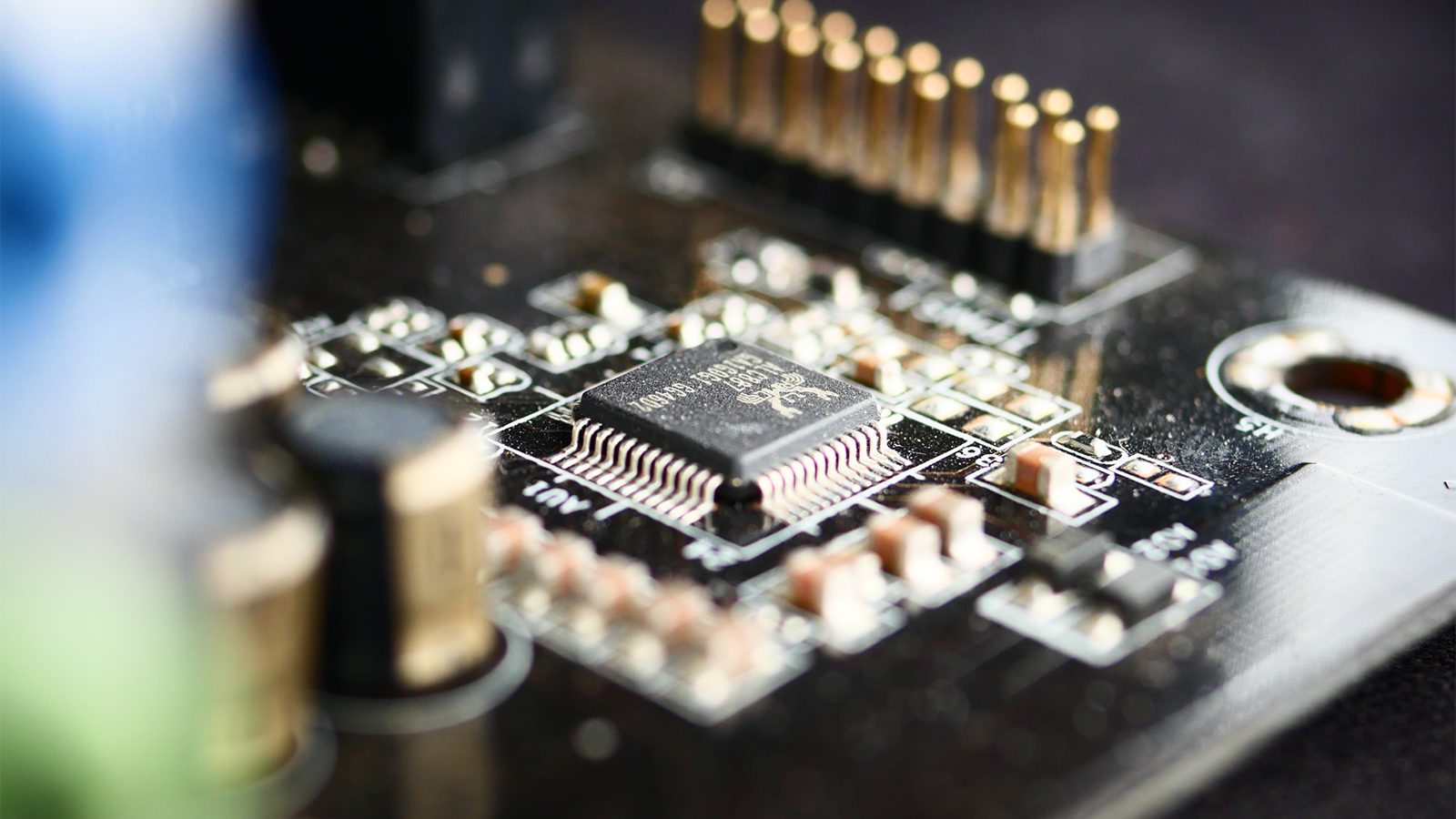

While US companies can still do cutting-edge design work, he explained, they have to send the design data overseas to get them fabricated, then wait for the prototypes to be shipped back before they can test them out. That creates at least three problems, he said:

- It increases the risk the designs will be stolen, either hacked in transit overseas or just illicitly copied by a foreign partner.

- It increases the turnaround time between coming up with a design and testing it, which slows what should be a tight iterative cycle of design-test-fix-redesign.

- It separates the design team from the engineers with the actual hands-on expertise in building the product, making it harder for them to share insights, give feedback, and generally spark off each others’ creativity.

So while the long-term goal of the 2022 CHIPS Act is to rebuild American manufacturing capacity for mass production of microelectronics, the first step is just recovering the capability to build a relative handful of prototypes. And after decades of offshoring, there’s now real enthusiasm for bringing that capability back, said Shenoy, who recently returned from a tour of all eight hubs.

The Microelectronics Commons coalition has experienced “phenomenal growth,” Shenoy said, from 380 organizations last December to “over 1,200” today. When Shenoy’s office put out the initial call for prototyping proposals, they asked each of the eight hubs to contribute 15 candidates, he continued; but just one hub, Boston, got about 75 proposals that it then had to whittle down — and there’s been a similar winnowing process at the other seven. That’s an intensity of engagement Shenoy aims to build on in future rounds of grants.

Aussie military inks contracts for quantum clocks to aid ‘maritime domain awareness’

The ADF statement carefully notes that these “are key objectives under AUKUS Pillar II,” but it does not claim that they are being done as part of the second pillar, which focuses on a range of advanced technologies, including quantum, artificial intelligence and autonomy.