M1 tank at the National Training Center at Fort Irwin, California.

WASHINGTON: Drones have decimated conventional armored forces from Ukraine to the Caucasus in regional conflicts. Should the US let its soldiers experience such disasters first-hand before the battle to inoculate them against real-life defeats and teach them the power of remotely operated weapons in a way they’ll never forget?

As a young officer, one senior general told an Army Futures Command conference this morning, some of his most powerful learning experiences came from losing against the elite Opposing Force (OPFOR) at the National Training Center.

“I learned … only because I got tired of going out to Fort Irwin and getting my rear end handed to me every time,” the general said. (Media were allowed to cover the conference as long as we didn’t identify individual speakers, to facilitate this kind of candid discussion). “Sometimes, the forced learning is the best way to begin.”

Humans check out a modified M113 converted into an experimental Robotic Combat Vehicle

Army Futures Command – indeed, the entire US military – is investing heavily in artificial intelligence, robotics, and automation. Senior leaders see these technologies as essential to victory against high-tech adversaries like Russia and China, who are making similar investments themselves. But how do you convince frontline commanders and individual soldiers to entrust their lives to such radically new technology?

After talking with one group of soldiers who’d experimented with remote-controlled Robotic Combat Vehicles, the general became convinced, he said, that “a lot of this comes down to trust, [and] trust in …. machines is difficult for a human.”

After months or years of training together, he said, “you trust the soldier on your right and left. You trust the soldier on your front and rear, and you trust your buddies are going to take care of you when you get into trouble. It’s difficult to trust an inanimate object when you don’t understand how it comes to the recommendations that it’s making.”

Part of the answer lies in how you design the user interface that presents recommendations to the soldier, the general said. (The Intelligence Community in particular is trying to develop “explainable AI” that can explain how it reached a given conclusion in ways a non-engineer can understand). But part of the answer lies in experience: Arguably the most convincing way AI can prove it works is by outsmarting you.

“It may be you force people to become trustful at places like the National Training Center,” the general said. As new AI-driven capabilities come online, he said, “maybe the first fielding of these kinds of systems is the OPFOR.”

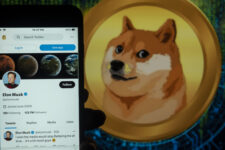

Mock-up of the Israeli-made IAI Harop (Harpy) “suicide drone” used by Azerbaijani forces against Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh

Donbass, Nagorno-Karabakh, & 1939

What kind of future disaster are we trying to prevent? Armenian losses in Nagorno-Karabakh in recent weeks, and Ukrainian losses in the Donbass in recent years, may offer up a lethal preview, the general suggested, just as the blitzkrieg of Poland in 1939 was a preview for the fall of France the following year.

What matters is not just new technology, but new tactics and organizations to use it. “When the Germans invaded Poland [in] September of 1939, [what mattered was] not new technology — because everybody had tanks. Everybody had radios. Everybody had airplanes — but a new way of combining technologies,” the general said.

“Until the rest of the world caught up,” he continued, that combination “gave them a significant operational and tactical advantage with what was in reality, only about 10 percent of their forces.” While the Panzers and Stukas made blitzkrieg possible, 90 percent of the German army remained infantry soldiers who marched into battle on foot and were often resupplied by horse-drawn carts.

German Panzers cross the Ardennes to take French forces by surprise, 1940.arm

What’s the 21st century equivalent? Perhaps a force like Russia’s or Azerbaijan’s, primarily armed with Cold War weapons but augmented with a cutting edge of unmanned systems that makes the whole force more effective. In the Donbass, Russia used drones to spot Ukrainian targets for swift, devastating barrages of artillery fire. In Nagorno-Karabakh, the drones themselves became the killing weapons, with Azerbaijan using Israeli-made Harpy (Harop) “suicide drones” bought from Israel and Turkey against Armenian armored vehicles.

Now, it’s as dangerous to overhype high-tech threats as to dismiss them. Numerous analysts have noted that both sides seemed badly trained. Videos show tight, easily targeted clusters of tanks advancing slowly across open ground or dug-in in static positions. In both cases, there was usually no proper cover, no camouflage, and no sign of infantry, artillery, or, most crucially in this case, mobile anti-aircraft defense (a capability that the US Army is urgently rebuilding).

Such tactics are suicidal whether the enemy has drones or not. As retired Army three-star Tom Spoehr told Military Times, US Army officers “learn that at the NTC the hard way,” without anyone actually dying in the process.

By contrast, despite their drones inflicting heavy losses on the Armenians, the Azerbaijanis suffered bloodbaths of their own when their infantry repeatedly assaulted Armenian trenchlines. While Azerbaijan made territorial gains, they were modest and costly. There was as much as World War I in evidence in Nagorno-Karabakh as innovation.

International volunteers man a Russian-built T-26 tank in Spain during the Civil War, 1937

So the Azerbaijani combination of new forces and old was clearly less sophisticated and successful than the Germans’ in 1939. Perhaps the better analogy would be 1937, amidst the Spanish Civil War, a bitter proxy conflict which combined cutting-edge technology with Keystone Cop tactics.

In the Republican offensive that year at Fuentes de Ebro, writes historian Steven Zaloga, Russian-built BT-5 tanks (ancestors of the famous T-34) advanced boldly against Fascist lines without coordinating with the infantry or conducting proper reconnaissance beforehand. After getting fired on by their own startled troops, the tanks discovered their path was blocked by muddy ground and irrigation ditches. Some 19 of 48 tanks were lost, a third of the crewmen were killed or wounded. Conversely, German tankers discovered their tiny PzKpfw I tank’s main weapon, a machinegun, just pinged comically off Russian T-26 armor at most ranges. Yet the manifest imperfections of the new technology were themselves valuable lessons to German advisors as they developed what would become the blitzkrieg.

The US Army is likewise putting prototype tech through brutal field-testing with real soldiers giving frank feedback. Compared to the similarly ambitious Future Combat System cancelled in 2009, “one of the fundamental differences, I’d say, is a healthy degree of skepticism,” the general said. “Another key difference is the willingness to bring stuff out and bring it to the breaking point.”

Next year’s Project Convergence exercise will bring in troops from the 82nd Airborne and the experimental Multi-Domain Task Force to test the new AI-enabled tech, which will hopefully enter service later this decade.

But at this weeks’ conference, the Army is already looking ahead to the dangerous world of 2035, when the Army expects China to outpace Russia as its greatest threat. “People tell me all the time that’s way too far in the future to be thinking,” the general said. “Well, 2035 is 14 years from now.” That’s less than the amount of time the typical lieutenant colonel has served in the Army.

“You’re going to blink your eyes and we’re going to be in 2035,” the general said. “If we don’t start investing in the development of those technologies…we’ll be at 2035 and we’ll still be saying, ‘we wish we could do that.’”

It’s not just technology we need to start developing, however. “It’s going to force a change in the Combat Training Centers,” the general said. “It’s going to force a change in PME — Professional Military Education — across the Army – if we do it right.”

Integrating commercial off-the-shelf computing on military platforms

Technology insertion into legacy platforms and electronics requires creativity in designing computer systems that can communicate with them.