THE CAPITOL: The Army’s ambitious modernization plan got a positive and receptive hearing this week from House appropriators.

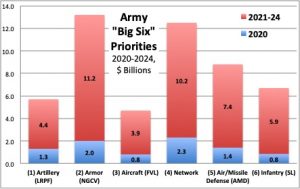

LRPF: Long-Range Precision Fires. NGCV: Next-Generation Combat Vehicle. FVL: Future Vertical Lift. AMD: Air & Missile Defense. SL: Soldier Lethality. (Click to expand)

Subcommittee members were more curious than critical. Chairman Pete Visclosky was outright coaching the Army Secretary and Chief of Staff on how to get their plan through Congress. That’s very different from the buzzsaw of opposition you might expect for a strategy mostly funded by canceling or cutting 186 lower-priority programs, all of them built in someone’s district.

Now, most of these cuts — and the additions to the Army’s Big Six priorities they pay for — come not in 2020 but in 2021-2024. And that just gets the Army halfway to the 2028 target date set by Secretary Mark Esper, which is long after he and Gen. Mark Milley will be gone.

So who’ll keep a steady hand on the helm? That continuity might come from the chief of the newly created Army Futures Command, whom Milley suggested might need “a seven or eight year term” to see the effort through.

Advice from the Chairman

Visclosky opened the hearing by congratulating Gen. Milley on his nomination to be chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Yes, he warned the Army not to repeat the acquisition disasters of the past, but the Indiana Democratic reserved any real ire for President Trump’s proposal to fund border security out of the Pentagon budget. He spent less time criticizing the Army leaders before him than coaching them.

“My concern — because Congress is a partner and has been at fault here — [is that] we can’t say ‘yes’ to a cut,” Visclosky said. “I assume you have talked to vendors about the adjustments that will be made as far the termination and reduction of programs,” he went on. “What about the members and senators in those districts and states? Are you having those conversations too, to plow the field for us when we get on the House floor?”

Already, Visclosky warned, “I heard from a number of people from a particular state that they are not happy” with cuts to the CH-47 Chinook heavy-lift helicopter (largely built in Pennsylvania). “Is the Army seeking out some of these members and doing an educational program,” he asked, on the need for the changes?

“We’ve had some very unpleasant experiences, [where] the theory is we pay for it with cuts; by the time we get done with the bill on the House floor, there’re no cuts, and we have to find more money [elsewhere],” Visclosky added. “I don’t want to get in a trap.”

Esper’s response? The Army secretary said, “the chief and I have probably met multiple dozen times with CEOs, either privately or in large groups, to explain where the Army is going.”

Visclosky replied: “The vendors and contractors, they’re not going to vote on this bill,”

“I’ve done some outreach with members but not as much,” Esper admitted.

“I would encourage the department to think about individual members, delegations, and locations,” Visclosky said. “If you want to be successful, we have to win those votes on the House floor.”

(Note he said “we have to win those votes,” not “you “).

Visclosky is an unusually reserved legislator, not one to pound his chest about supporting the troops, and he kept any hint of frustration out of his voice. But he’s signaling pretty clearly that he both supports the Army plan and worries the service isn’t campaigning hard enough for it on Capitol Hill.

The head of Army Futures Command, Gen. Mike Murray, and Army Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Milley, formally unfold the new command’s colors in Austin in August 2018.

Tenure For Futures Commander?

To sustain that campaign year after year, it would be ideal to have a single, steady hand at the helm. The great example is Adm. Hyman Rickover — the longest-serving naval officer in the nation’s history — who led the Navy’s transition to nuclear power for decades. Gen. Milley cited Rickover as a model back in fall 2017 when he first rolled out the modernization plan (before Esper was even nominated for the secretary job), and he brought the admiral up again in this week’s hearing.

“That’s what we want in Futures Command, is the continuity of effort over multiple secretaries, multiple chiefs,” Milley told Congress.

Milley doesn’t think the Army can implement the “Rickover model” with the current (and first) chief of Army Futures Command, Gen. John Murray. “Murray’s a pretty senior guy, he graduated around the same time I did ,” Milley said. “He’s getting long in the tooth, so he’ll time out after a few more years.”

But, Milley went on, “when we appoint that person whoever that next person is, we’re looking at probably a seven or eight year term.”

Actually, it might be possible to extend Gen. Murray’s service this long, but since he already has 37 years in uniform, it might require a waiver from the Secretary of Defense. The regulations are convoluted: The Army’s official mandatory retirement date website requires entering your rank, years in service, date of commissioning, and more, and even then the online calculator doesn’t work for four-star officers. I couldn’t find anyone in the Army who’d explain just how the rules would apply to Murray — assuming he’s not simply too exhausted to continue after a few years in a tremendously demanding job.

Moving to the Rickover model is clearly just an idea at this point, very far from a fully formed plan. But it’s an idea both the Army’s senior leaders like.

“We’ve got to work through the details,” Esper told me after the hearing, “but…what you want is long terms for these guys in that role, because the continuity is important with regard to managing long-term programs.”

Will giving the Army Futures commander a longer tenure require congressional action, I asked, or can the Army do it under its existing authorities?

“We’ll have to see,” Esper replied.

Milley sounded more confident: “It’s within his authorities,” he said, pointing at Esper.

From a new civilian leader to modernization priorities, Army changes afoot: 2025 preview

As the Army heads into the new year, it will be greeted with questions about weapon affordability and ways to carve out efficiencies.