Yesterday’s Senate passage of the budget deal took $20 billion worth of pressure off the Pentagon. But for the Army the deal just dials the pain back down from “agonizing” to “acute.”

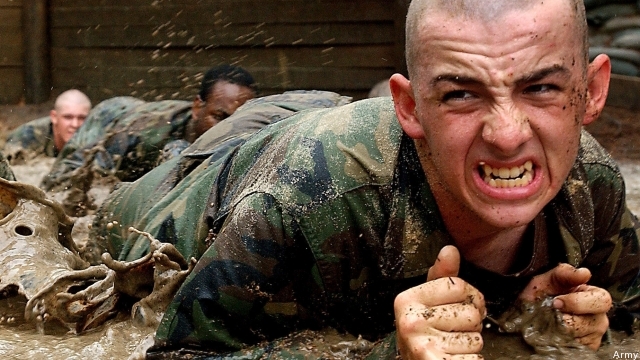

The largest service has more to lose in the post-war drawdown (which happens to have begun before the war is actually over). In fact, the Army is losing a lot already: its top-priority weapons program; some 80,000 people; even its ability to keep all its units fully trained and ready; and there’s more to come, even though the Army got the sequester slowdown that its top brass has begged for.

So the Army’s challenge for 2014 isn’t to stop the bleeding: It’ll be hard enough just to slow it down. To do even that, the Army needs to make a compelling case to Congress, the White House, and the American people for the relevance of large and usually heavy land forces in the post-Afghanistan, Pacific Pivot era – which so far it hasn’t done.

That’s not for lack of trying. Army leaders point out, rightly, that they provide a host of services to the whole joint force, from overland logistics to communications. As units come off the treadmill of repeated Iraq and Afghanistan deployments, the Army is starting to assign them to theater commanders around the world as “regionally aligned forces,” ready for overseas missions from disaster relief to training foreign troops. The Army’s Special Forces in particular argue that to build lasting relationships, you need troops on the ground – an argument both the conventional “Big Army” and the Marine Corps have taken up.

But, truth to tell, none of these missions requires a large land force. The Army’s already shrinking from its wartime peak of 570,000 down to 490,000, but that’s slightly above its pre-9/11 level. Everyone expects it to shrink further; the question is how much. One team of thinktankers led by the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Clark Murdock proposed slashing the regular active-duty army to 327,000.

The Army’s foundational argument is the same it has been since at least the 1950 Task Force Smith disaster in Korea: The nation needs the firepower to win a large, prolonged land war, and history proves such wars break out when you don’t expect it. With the self-inflicted exception of Iraq in 2003, every major war we’ve fought since 1898 has occurred in spite of a stated US policy not to fight one: Woodrow Wilson ran in 1916 on the slogan “he kept us out of war;” isolationism prevailed in World War II until Pearl Harbor; Korea came as a shock; Kennedy promised no large ground forces in Vietnam; and few expected Saddam Hussein to conquer Kuwait or for Osama bin Laden to destroy the World Trade Center.

But after 12 years of war, that’s not an argument many people want to hear. The January 2012 Defense Strategic Guidance only swears off “large-scale, prolonged stability operations” – emphasis ours – but no less a figure than Vice-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Adm. James Winnefeld, recently told an Army audience that the country could not afford a ground force sized for “an extended war of any type.”

To the extent America needs an insurance plan against a big ground conflict, runs this school of thought, we can keep the needed personnel on retainer in the Army Reserve and National Guard, then mobilize them as needed. Clark Murdock & co. in fact recommended adding 100,000 personnel to the Reserves and Guard to make up for their deep cut to the regular Army. It is true that part-time troops have more than proven their worth since combat since 9/11. They’ve sped up too: Even a full-sized Guard brigade can now go from civilian life to combat readiness in 50 to 80 days.

But will there be enough regulars left to hold the line for those 50-plus days? (It’s politically unlikely any president would call up the Guard in large numbers before the fighting had actually begun). Even the soft-spoken Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Martin Dempsey, has publicly worried that the military as a whole – active, reserve, and Guard combined – won’t have the needed “depth” for a large war.

The Army’s immediate problem is persuading political leaders that it’s worth buying insurance against an unexpected, large scale ground war like Korea in 1950 (or Korea tomorrow in light of the erratic Kim Jong Un). Perhaps the most likely big-ground war scenario is what some in the Army are calling “war in the megacity.” As Third World populations cram into ever larger and more dysfunctional urban sprawls, the odds are one is eventually going to blow – and if even 1 percent of a population of 10 million takes up arms, that’s a force of 100,000. If a future president decides such a catastrophe requires the US to act, he or she may want a lot of ground troops in a hurry.

As Election Day looms, what Trump and Harris presidencies will (and won’t) mean for defense

While analysts told Breaking Defense a Trump administration would likely be a more unpredictable one, they also said that equally, if not more important, will be whichever party controls the houses of Congress where the defense budget is crafted.