Navy E-2D Advanced Hawkeye

NORFOLK: The famed “eyes of the fleet” are getting sharper. The Navy has declared the latest variant, the E-2D radar plane, ready for real-world operations just in time for the 50th anniversary of the original E-2 Hawkeye. The first five-plane squadron will deploy on the USS Theodore Roosevelt next year. Meanwhile, the current E-2C models are playing an essential role in the Middle East, launching from the USS George Bush to serve as flying command posts and air traffic control for the ongoing strikes against the self-proclaimed Islamic State.

“The CAG [Carrier Air Group] and the admiral would not go into harm’s way without an E-2,” said Capt. Drew Basden, commodore of the Navy’s Hawkeye force, “and that’s an E-2C.” While almost indistinguishable to the eye, the new E-2D version brings a much more powerful and discriminating radar — so much so, Basden told reporters visiting here, that the D may eventually do ballistic missile defense. That remark is one clue among many that the Navy wants the Advanced Hawkeye not just to do the current E-2C’s job better, as critical as it is, but to play a larger role.

Capt. Drew Basden

One sign of that larger role is simply a larger squadron: There’ll be five Ds aboard each carrier instead of the current four Cs. That squadron size, in turn, helps drive Navy plans to buy 75 of the $150 million Advanced Hawkeyes, more than the maximum number of Cs ever in service. (Only 52 “Charlies” remain today due to aging and accidents). Five planes per carrier is still probably not enough to keep one in the air at all times, but it will allow more constant coverage. An E-2D can stay aloft about five hours at a time on its own fuel, but in August the Navy completed the preliminary design review for an upgrade to allow mid-air refueling, something no Hawkeye has ever had.

Even with aerial refueling, though, the Hawkeye’s human crew will limit its endurance. The Navy’s new MQ-4C Triton reconnaissance drone, for example, is designed for 24-hour missions, although its size restricts it to land bases. The future Unmanned Carrier-Launched Surveillance & Strike (UCLASS) drone, while compact enough to operate off a carrier, will be designed to fly for 14 hours. (Unlike the Hawkeye and Triton, the UCLASS will also be armed, albeit lightly and controversially). Even the modestly sized MQ-8C Fire Scout, an unmanned helicopter able to operate off small vessels, can stay aloft for 10-12 hours.

E-2C Hawkeye aboard ship.

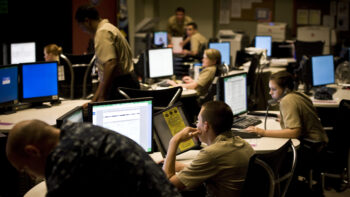

But shorter missions is the price Hawkeye must pay for having human brains aboard, which are essential to its role as a flying command post that can direct air operations without relaying every tactical decision back to the carrier. Robots are great at carrying radars and other sensors, but not at sorting out the real-time chaos of combat, let alone making life-or-death decisions.

How the Advanced Hawkeye will interact with the Navy’s expanding drone force is still up in the air. The E-2D’s bandwidth and other electronic capabilities are much greater than the C model’s, and there’s talk of upgrading the new Hawkeye to receive feeds from drones or to even control them, but that’s not in the current program. “With respect to any additional requirements to communicate with UAVs [unmanned air vehicles], those requirements are being looked at,” said Capt. John Lemmon, the E-2 program manager at Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR).

The E-2D also carries unspecified “electronic support measures” (ESM) equipment and will play a significant role in the Navy’s new vision of “electromagnetic maneuver warfare” — but these systems are so highly classified that the Navy officials at Norfolk politely refused to provide any detail.

Capt. John Lemmon (left) and Cdr. John Heweitt (right).

What the service will say is that the Hawkeye is central to its new network for long-range warfare against enemy planes and missiles, Naval Integrated Fire Control – Counter Air. NIFC-CA shares detailed targeting information across the fleet, giving each linked ship and aircraft a much clearer picture of the enemy that it could get using its own sensors. An Aegis destroyer, for example, might use NIFCA-CA data to shoot down a distant enemy beyond the range of its own shipboard radars. While some modernized E-2Cs have the same datalinks that the E-2D has, the Advanced Hawkeye has a much more powerful, precise radar to provide targeting data to the network.

“The Delta’s linkage to NIFC-CA has everything to do with the radar,” said Cdr. John Hewitt, who runs E-2D training. “The precision that you would need… you could not do in the Charlie [i.e. the E-2C].” The C-model, with its traditional mechanical radar, was designed to combat a Soviet-style threat — “think Tu-95 bear bombers and Udaloy destroyers,” Hewitt said — in “blue water” far from shore. “It’s still doing that job very well, [but] it had its limits in a littoral/over-land environment,” he said. The D-model’s solid-state radar, by contrast, can pick up “very small contacts, air and surface, over land, over water,” he said. “The aircraft does not care.”

An E-2C Hawkeye (left) and an E-2D Advanced Hawkeye (right). While almost indistinguishable from the outside, the D carries a much more powerful radar and electronics.

Army halted weapon development and pushed tech to soldiers faster: 2024 in review

The Army spent 2024 pushing its new “transformation in contact” initiative while also pivoting away from several key weapon development initiatives.