WASHINGTON: The European Union has taken a major step toward more effective national security screening of foreign direct investments, implementing a new “framework” for the EU.

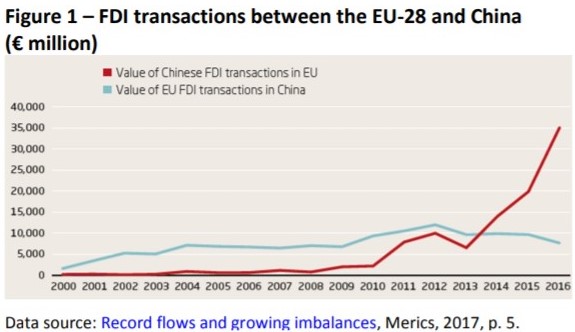

It is the beginning of a more unified approach across the vast market on a long-standing issue. Even though China is not explicitly targeted in the new document, the timing of this new legislation comes as EU leaders met for two days to prepare for the April 9 EU-China Summit. That was no accident. A key indicator about the importance of the Chinese issue is found is this line from the latest European Commission Report about China: “China can no longer be regarded as a developing country.” That sentence sums up the change of mood in Europe regarding everything Chinese. One can identify several triggers to the switch.

- The coming to power of President Xi Jinping and his new strategic vision embodied in China’s five-year plan (2016-2020) and Made in China Strategy (2015) and implemented with the development of a more aggressive approach to strategic assets, such as the Silk Road Fund and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) meant to support the global One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative;

- The increasing number of Chinese acquisitions or attempts to control strategic assets. To name just two: the Greek port of Piraeus, purchased by the state-owned COSCO Shipping. COSCO bought 67 percent of its capital in 2016. Priraeus is part of the 29 ports and 47 terminals now ran by Chinese companies in more than a dozen countries in Europe and elsewhere. Another recent example is the debate over the fate of the Toulouse airport, located at the heart of France’s aerospace industry and research community. The Chinese consortium Symbiose’s firm Casil owns 49,99 percent;

- A new willingness to promote a true European defense – prompted by Russian actions starting with Ukraine and Crimea, as well as other factors such as Brexit, President Trump’s rhetoric about NATO allies, the arrival of President Macron in power with a passion to rebuild the old Franco-German fulcrum in European institutions.

Europeans have clearly come to accept that they must protect their industrial base both for economic reasons and for security reasons. Infrastructure and mobility are for instance now hot topics in the EU, each member being for instance required by the end of the year to establish national plans for military mobility and focusing on improving interoperability.The same goes for cyber and network security, as the debate about Huawei’s 5G mobile network investment in Germany (with the US warning about reduced intelligence sharing with Berlin if the deal goes ahead) shows. There has been a similar debate in France, but the battle there is more about “digital sovereignty” and the promotion of a European champion that can compete with what Europeans call the GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon), which are now required to pay a tax based on their revenue generated in France.

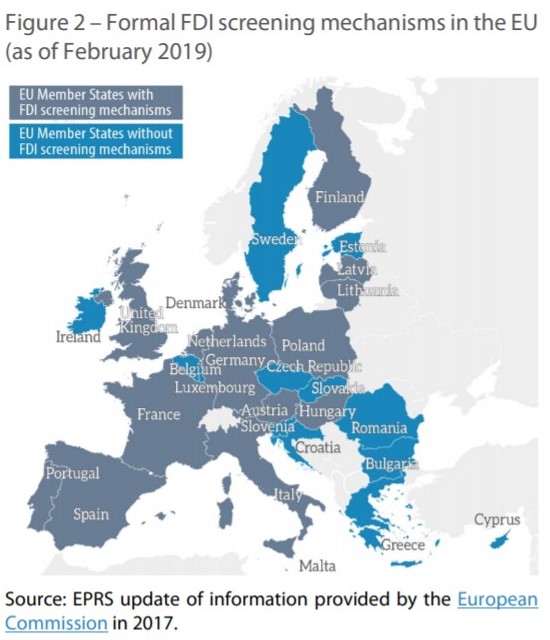

Indeed if China is most targeted by the EU’s new policy, Russia is also central and is the reason why Nordic countries finally came on board with the new screening legislation.

So what does this new legislation really mean ?

One can compare the new mechanism to the US Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS). It provides a way to monitor foreign direct investments on a EU-wide basis. The regulation states the main objective: to provide… the means to address risks to security or public order.

Key to the new approach is language granting individual members the right to take”into account their individual situations and national specificities. The decision on whether to set up a screening mechanism or to screen a particular foreign direct investment remains the sole responsibility of the Member State concerned.”

As anyone who has done national security business in a European state knows, not all EU members possess the national means to effectively monitor and enforce standards and policies and preferences differ a great deal among them.

Source : EU Framework for FDI Screening, European Parliament

Article 8 of the new regulation details the range of targeted investments — anything “regarding critical infrastructure, critical technologies or critical inputs which are essential for security or public order.” That includes dual-use technologies – such as artificial intelligence, robotics, nanotechnologies. But it also includes sectors related to energy, data processing and storage, health, transportation, communications. The supply chain and access to strategic resources (including food security) should also be affected. Cyber also, with, in addition a new focus on access to personal data, as well as on media freedom….

It requires member states to inform the European Commission about foreign direct investments when relevant; other member states can only comment:

The final decisions about “any measure taken in relation to a foreign direct investment not undergoing screening remains the sole responsibility of the Member State where the foreign direct investment is planned or completed.” So, while there is a new paradigm, it is voluntary, in contrast to the US model.

Even though the system is not mandatory, European analysts and business lawyers share three broad areas of concern;

- it may affect the reputation and competitive edge of the EU as the most welcoming trade partner at a time of slow growth when investments are crucial. Indeed, with the value of exchange of goods between the EU and China larger than1.5 billion euros a day, the EU is China’s biggest trading partner and China is the EU’s second after the United States. The stakes are high and many European countries – especially those without a strong industrial base – desesperately need these investments – whether in infrastructure like the 16 + 1 Group – a group gathering 11 EU members and 5 Balkan countries under the initiative of China and focusing on the funding of projects such as the Belgrade-Budapest High Speed rail, or other ares such as health (recent shortages of drugs in Europe have highlighted our overall dependency on Asia in this crucial public health field as well…) -.

- Even though not constraining, the regulation may be enough to discourage investors, as more time, uncertainty about feasability and therefore cost could be the ripple effects, especially for firms with Chinese ties which will go under more scrutiny.

- It has already an impact on national legislations being reinforced or established, while the new regulation will be adding an extra layer in a bidding process complicated enough, and could be used to break deals or favor other competitors, even through mere political exposure and pressure.

It happened in the past both in the United States with the CFIUS system and in Europe just through resolution, and it is indeed the goal and the deterrent impact which the legislators hope to achieve with this new bold statement.

However, as the signing into law last summer of the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) by President Trump shows, the initial CFIUS mechanism seems to have been circumvented by Beijing via other means, such as real-estate acquisitions and technology transfer through joint-ventures, to name a few.

The new battle emerging from Brussels means President Trump is not alone anymore in his focus on protecting America’s industrial base. But then again, China and Russia don’t worry much about a level playing field.

An annex related to Article 8 lists specific programs connected in particular with space, telecommunications, energy and transportation:

List of projects or programmes of Union interest referred to in Article 8(3)

- European GNSS programmes (Galileo & EGNOS):

Regulation (EU) No 1285/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2013 on theimplementation and exploitation of the European satellite navigation systems and repealing the Council Regulation (EC) No 876/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 683/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council (OJ L 347, 20.12.2013, p. 1). - Copernicus:

Regulation (EU) No 377/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 3 April 2014 establishing the Copernicus Programme and repealing Regulation (EU) No 911/2010 (OJ L 122, 24.4.2014, p. 44). - Horizon 2020:

Regulation (EU) No 1291/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2013 establishing Horizon 2020 – the Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (2014-2020) and repealing Decision No 1982/2006/EC (OJ L 347, 20.12.2013, p. 104), including actions therein relating to Key Enabling Technologies such as artificial intelligence, robotics, semiconductors and cybersecurity. - Trans-European Networks for Transport (TEN-T):

Regulation (EU) No 1315/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2013 on Union guidelines for the development of the trans-European transport network and repealing Decision No 661/2010/EU (OJ L 348, 20.12.2013, p. 1). - Trans-European Networks for Energy (TEN-E):

Regulation (EU) No 347/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2013 on guidelines for trans-European energy infrastructure and repealing Decision No 1364/2006/EC and amending Regulations (EC) No 713/2009, (EC) No 714/2009 and (EC) No 715/2009 (OJ L 115, 25.4.2013, p. 39). - Trans-European Networks for Telecommunications:

Regulation (EU) No 283/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 2014 on guidelines for trans-European networks in the area of telecommunications infrastructure and repealing Decision No 1336/97/EC (OJ L 86, 21.3.2014, p. 14). - European Defence Industrial Development Programme:

Regulation (EU) 2018/1092 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 July 2018 establishing the European Defence Industrial Development Programme aiming at supporting the competitiveness and innovation capacity of the Union’s defence industry (OJ L 200, 7.8.2018, p. 30). - Permanent structured cooperation (PESCO):

Council Decision (CFSP) 2018/340 of 6 March 2018 establishing the list of projects to be developed under PESCO (OJ L 65, 8.3.2018, p. 24)

Poland signs $300M lease for Apache attack helicopters

The deal, which covers eight AH-64Ds, will serve as a capability bridge until the first of 96 newly-bought Apaches arrive starting in 2028.