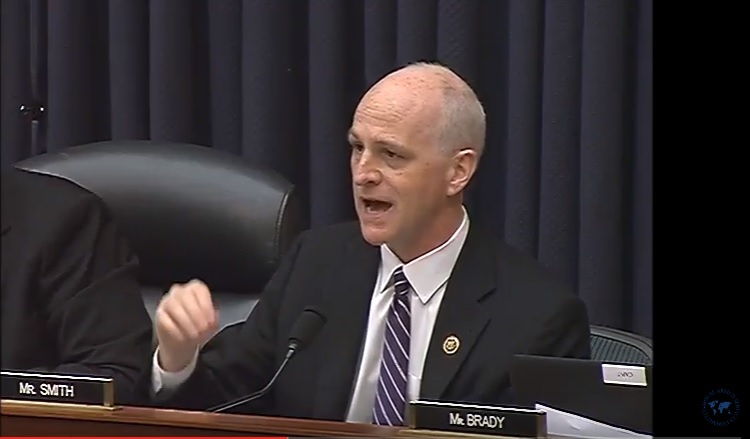

Rep. Adam Smith, House Armed Services Committee Chair

WASHINGTON: House Armed Services Committee (HASC) Chair Adam Smith didn’t act on the White House proposal to spend $72.4 million to launch a new Air Force-embedded Space Force in the draft version of the NDAA. This is a clear sign of the proposal’s divisiveness, including among House Democrats. While Smith has opposed the proposal language sent to Congress by the Pentagon, Rep. Jim Cooper who chairs the HASC strategic forces subcommittee that oversees military space policy, is a staunch supporter (the cosponsor of last year’s bill promoting the new concept.)

Smith told reporters this morning that the two parties representatives couldn’t agree on language in time for the mark-up.

“We were in negotiations over the language to go into the bill [but] it took a little time. So by the time we got to an agreement it was too late to put it into the original mark,” he said.

So the issue will be dealt with in the amendment process when the bill comes to committee vote on June 12.

Smith declined to offer much on what the amendment might contain, but said it would draw heavily on the proposal for a “Space Corps” agreed by the HASC in its 2018 version of the NDAA, that was ultimately rejected in conference with the Senate. (That version was co-sponsored by Cooper and then-Strategic Forces Subcommittee Chair Mike Rogers.) The amendment will propose a “smaller and more focused” plan than the blueprint put forward by the Pentagon, Smith said.

“The main difference from the administration’s approach is less bureaucracy,” he explained. We don’t have three four-stars. We only have the one,” Smith said.

At the same time, he doubled down on his longstanding criticism of the Air Force regarding management of US national security space programs, exactly the reason behind the push for a Space Corps or Space Force in the first place.

“I don’t trust the Air Force, on its own, given its existing structure to properly prioritize space,” Smith said. He added: “I think the Air Force has not done a particularly good job of managing space. And if I was not in a breakfast setting with a bunch of reporters I would put that much less diplomatically. They’re not doing a good job.”

The Trump Administration proposal would create the new force under the Air Force in a manner similar to the Marine Corps’ organization under the Navy. The Senate Armed Services Committee for its part has endorsed the move, albeit with some changes — and some ambiguity about whether and when the new force would integrate Army and Navy space programs and personnel. The House Appropriations Committee (which sets the spending limits on Pentagon programs), for its part, approved only $15 million for the Pentagon to study the proposal, and no funds to begin implementation. The Republican-controlled Senate Appropriations Committee is likely, however, to approve the full administration request.

The chair’s markup takes plenty of other action on space issues and programs, following closely last week’s markup by the HASC strategic forces subcommittee, which chopped the Air Force’s budget request for new missile warning satellites, one of its top research and development priorities. The committee cut $376.4 million from the Air Force’s request of $1.4 billion (almost double last year’s funding level) for RTD&E on the Next Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared (Next-Gen OPIR) constellation of five satellites. The program is being designed to replace the (long troubled) Space Based Infrared System (SBIRS). The Air Force requested nearly $200 million to continue SBIRS procurement.

The House Appropriations Committee (HAC) on May 21 set a ceiling of $1.395 billion for Next-Gen OPIR, a cut of almost $202 million to the Air Force’s $1.4 billion request. The House appropriators also restricted spending on the program to no more than 50 percent of the total until the Pentagon’s new Space Development Agency (SDA) and the Air Force providing Congress with a detailed blueprint of how they will coordinate on space systems research, development and procurement and parcel out oversight of new programs.

The HASC took several other actions to force the Pentagon’s hands on space policy and programs. According to a summary by the subcommittee that oversees DoD space these include:

Launch Competition. The HASC summary states that the bill “introduces opportunities for increased fair and open competition in launch,” referring to the Air Force’s mega-million National Security Space Launch Phase 2 contract to replace the long-standing Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle program. Competition among the four competitors — Northrop Grumman, United Launch Alliance, Blue Origin and SpaceX — is fierce and has been plagued by controversy, including intervention by Smith (who in March set a letter to then-Air Force Chief Heather Wilson asking for the process to be delayed) and most recently a lawsuit by Space X. The two winners will split contracts for up to 25 launches between fiscal year 2022 and 2026.

Smith, whose congressional district is home to Blue Origin, did not go into many details, saying: “What we’re doing here is perfectly consistent with the goals of the launch competition.” He added that “if SpaceX is one of those two companies, they should get the launch assistance they would have gotten if they were awarded the contract the first time.” The other three competitors in October 2018 were awarded “Launch Service Agreements” worth a total of $2.3 billion, to help them bring their new rocket concepts up to speed — and this is one of SpaceX’s complaints.

GPS Receivers. Requires SDA to establish a program to prototype a navigation satellite system (GNSS) receiver, base on the classified DoD M-code signal, “that would incorporate both allied and non-allied, trusted and open GNSS signals to increase the resilience and capability of military positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) equipment.” Congress wants the receiver to be compatible with Europe’s Galileo network and Japan’s QZSS satellites as well as the US Global Positioning System (GPS), and for the Pentagon to try to make it ready for the GPS III satellites. The first of 10-planned GPS III satellites was launched in December 2018; the last is to be launched in 2023 when an updated ground station (Raytheon’s OCX, designed to improve M-code strength among other advances) is also due to be ready for fielding. The House bill would limit funding for the GPS Military Equipment User Program until a briefing and report on the implementation plan have been submitted to Congress.

Space Situational Awareness. The HASC would require the SDA to issue at least two contracts for commercial Space Situational Awareness (SSA) services, citing delays and increased costs in the long- and deeply troubled Joint Space Operations Center’s Joint Mission System. The Air Force actually canceled the program in 2018, in favor of a new initiative — one that would rope in the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) — called the Enterprise Space Battle Management Command & Control (ESBMC2). In the meantime, it is filling in by gerry-rigging the ancient Space Defense Operations Center (SPADOC) system to ensure that SSA data can still be crunched. The HASC is peeved because there are a number of commercial vendors who could have taken on the job with more modern and capable systems. The bill says: “Multiple commercial vendors have the current capability to detect, maintain custody of, and 21 provide analytical products that can address the warfighter [needs.]”

The HASC further requires that SDA and the Air Force deliver a report by Jan. 1, 2020 that includes:

- A description of current domestic commercial capabilities to detect and track space objects in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) below the 10 centimeter threshold of legacy systems.

- A description of current domestic best-in-breed commercial capabilities that can meet such requirements.

- Estimates of the timelines, milestones and funding requirements to procure a near-term solution to meet such requirements until the development programs of the Air Force are projected to be operationally fielded.

There are several US companies vying to provide commercial SSA data and services to satellite operators, including the Air Force: Analytical Graphics Inc. (AGI) — one of the first in the field, defense prime Lockheed Martin and telescope operator ExoAnalytic Solutions. Market research firm Research and Markets in June 2018 predicted the market for SSA services would hit $1.44 billion by 2023.

Missile Defense. The HASC markup would prohibit “any missile defense capability that could only be deployed in space,” according to a summary provided to reporters this morning, and further would reverse the Republican-backed requirement in last year’s NDAA for stand-up of a space-based missile defense test bed. It also directs the Missile Defense Agency (MDA) to continue work on a space-based sensor payload for tracking ballistic and hypersonic threats from space, authorizing $108 million — copying the action by the Senate in its version of the NDAA in May

The committee also “directs the Director of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) to conduct a comprehensive AOA on current boost-phase technologies being developed or investigated,” by March 31, 2020, according to the strategic forces’ markup. The subcommittee’s version of the bill expresses skepticism in particular about the MDA’s plan to spend $34 million to initiate development of a space-based neutral-particle beam weapon for destroying enemy ICMBs in their boost-phase shortly after launch.

The Chairman’s markup further “requires more robust testing” of the Navy’s Standard Missile-3 Block IIA (SM-3 Block IIA) “against threats for which it was designed due to the missile experiencing several flight test failures” putting off planned testing against an intercontinental ballistic missile. The Aegis-launched SM-3 Block II is a joint development with Japan, and is being designed to be deployed in Aegis Ashore stations in Romania, Poland and Japan for intercepting short- and medium-range ballistic missiles. The missile has failed two out of four of its tests.

According to the HASC summary, the bill “addresses program delays in the Redesigned Kill Vehicle (RKV), and cuts unjustified cost growth across the Ground Based Midcourse Defense system.” The summary does not provide a figure for the cost cut; the Pentagon asked for $1.7 billion for the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD) program. The HASC move comes in the wake of a new Government Accountability Office (GAO) report showing that the Missile Defense Agency’s effort, led by Raytheon, to develop a new interceptor kill vehicle (that is, the missile’s inert, kinetic energy warhead) for GMD is experiencing “development challenges that set the program back likely by over two years and increased the program’s cost by nearly $600 million.” The GAO report, released on June 6, notes that in light of the RKV’s problems, the agency on May 24 ordered prime GMD contractor Boeing to stop work related to its integration.

Finally, the HASC demands Pentagon reports on a number of space policy issues — reflecting the committee’s broad unease with the Trump Administration’s direction.

The summary of the chair’s mark calls for DoD to contract an independent study on space deterrence to “improve policies and capabilities to deter conflict in space.”

It also calls on the Pentagon to report by the end of December progress in offloading some military communications to commercial satellites, and on progress toward development of small satellite constellations in LEO to replace or augment DoD space-based systems including the Defense Advanced Projects Agency’s Blackjack experimental program.

From Boeing’s struggles to inflation relief funds: 5 industry stories from 2024

Making a year-end list in which she forces references to Taylor Swift songs for no reason has basically become reporter Valerie Insinna’s favorite Christmas tradition.