Gen. James McConville checks out the upgraded cockpit of the new UH-60V “Victor” model, which will be mainly used by the National Guard.

WASHINGTON: The Army Chief of Staff is working with his Air Force counterpart to link the two services’ networks into a single joint command system for future conflicts.

“We are moving out on it. In fact, I’ve talked to the Chief of Staff of the Air Force [Gen. David Goldfein],” Gen. James McConville said at the Atlantic Council this morning. “Our staffs are meeting right now.”

“We’ve got a conference going on,” McConville told me after the event. “I’m surprised you’re not out at it.” (Well, we would be, but it turns out press isn’t allowed: Click here for more on the high-level meetings at Ellis Air Force Base).

“We know we need a joint command and control system; we’ve got to have that. We understand that,” McConville said. But, he went on, each service has already invested so heavily in its own networks that it can’t just set aside what it has while waiting for a future Joint All-Domain Command & Control (JADC2) system. To the contrary, McConville seems to see those service-unique systems as essential building blocks to be pieced together into a future all-service system.

Gen. James McConville

In the Army, for instance, McConville said, “we’re very aggressive on [developing] the Integrated Tactical Network for our soldiers so they can operate in this contested environment” – that is, in the face of sophisticated jamming and hacking that would scramble current communications systems.

Further, he went on, “we have an Integrated Battle Command System that has been successful in recent tests and we’re excited about that.” That’s because IBCS will let any Army radar pass targeting data to any Army anti-aircraft or missile defense launcher – and recently it’s tested a link to an F-35 fighter as well. That’s a first step to the “any sensor, any shooter” capability JADC2 envisions linking all four services in all five domains – land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace.

The Air Force, likewise, is developing its Advanced Battle Management System. “We want to make sure we can all plug in,” McConville said, but the Air Force ABMS isn’t a universal solution: It’s “air-centric,” he said.

(Many in the Air Force might bristle at this description: They see ABMS as the backbone for the future joint command and control network, not just one component, and they’ve busily adding a host of data management and cloud computing systems to support it).

“So how do we bring those systems together so we can all talk … and pass data on a contested battlefield?” McConville asked. “That’s what we want to do.”

AH-64 Apache

Multiple Dilemmas & Minimal Manning

Building better networks isn’t about IT efficiencies. It’s a military imperative for the services to share information so they defeat advanced adversaries like China and Russia.

There’s precedent for this kind of cooperation, just not on the scale a 21st-century great power conflict would require. McConville, a career helicopter pilot himself, noted that the first shots of the 1991 Gulf War were fired by Army AH-64 Apache gunships, slipping in at low altitude to destroy Iraqi radars and open a gap for Air Force strikes. For a further joint twist, the Apaches’ pre-GPS navigation systems couldn’t lead them to the target, so Air Force helicopters led the way. By contrast, in 2003, when Apaches tried a “deep strike” through the Karbala Gap without proper support from the Air Force or ground units, they were spotted by Iraqi ground troops and shot up so badly they had to break off.

The lesson? “If you just take a bunch of Apaches and you have them fly – charge in like the charge of the Light Brigade – you’re probably not going to be successful,” McConville said. “But if you have ground forces coming, and you have aerial forces coming, you have unmanned forces coming, and you have artillery, and you’ve got a combined-arms joint-type fight, it presents multiple dilemmas to the enemy, and they can’t be everywhere.”

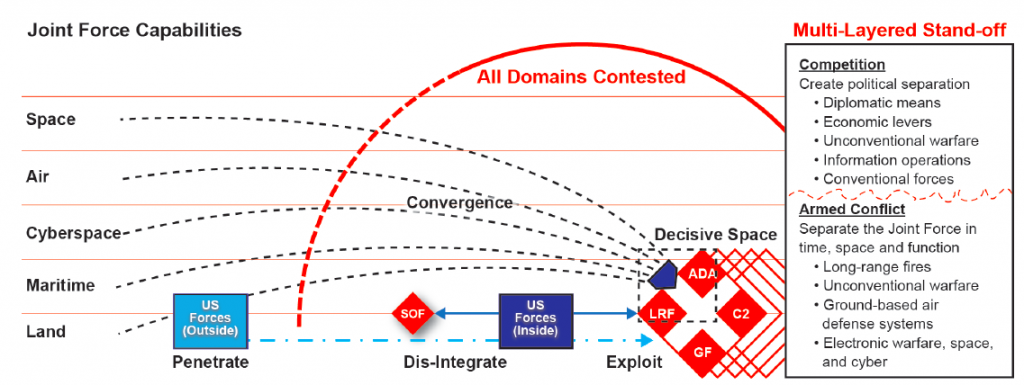

SOURCE: Army Multi-Domain Operations Concept, December 2018.

Joint All-Domain Command & Control is all about achieving that kind of lethal synergy, he said. For instance, decades after scrapping its Pershing ballistic missiles under the now-defunct INF Treaty, the Army’s top investment priority is what it calls Long-Range Precision Fires, including new missiles with ranges in the hundreds or even thousands of miles. The service doesn’t promote these ground-launched long-range weapons as a substitute for jets and helicopters, but as a vital supplement, able to (say) destroy enemy radars to open a path for airstrikes.

It’s a 21st century version of the Apache strike that opened the Gulf War, McConville said. “You’re still going to have to penetrate,” he said, but you’d do it differently today.

“An integrated air defense system is not very good against long-range precision fires, because radars are very susceptible to being taken down,” he said. “That allows you to open up holes and then to exploit [them], whether you’re using maritime forces, you’re using air forces, you’re using ground forces, or a combination.”

But will those future forces be manned or unmanned? McConville said he doesn’t like that kind of “either-or.” Instead, he explained, “what I see, especially in the near term, is where we’re going to be able to go to more minimum manning, where we have less people in aircraft, less people in some of our Army vehicles” – but not none.

That’s why the Army’s top-priority aviation programs – the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft to scout, the Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft to carry troops – are supposed to be “optionally manned,” able to fly with two pilots, one or none, depending on the complexity of the mission.

There is tremendous potential to use virtual and augmented reality to let humans remote-control unmanned vehicles as if they were on the scene themselves, McConville said. But no one’s yet built a machine equivalent for the sensory input a skilled pilot or driver gets from actually being in the vehicle, feeling the acceleration and resistance, able to see and hear in all directions, instead of just staring at a narrow screen.

“[With] drones, you’re looking through a soda straw, you’re only seeing what that camera’s seeing,” McConville told reporters. “There’s times when unmanned systems are good; there’s times when you want a person there, because you can’t feel it when you’re not there.”