WASHINGTON: Air Force Research Laboratory plans to solicit industry ideas for its ground-breaking lunar patrol satellite concept by the end of the year, says AFRL program manager Capt. David Buehler.

“We are in the process of writing a Request for Information, that we hope to have published by the end of 2020,” he told me in an email.

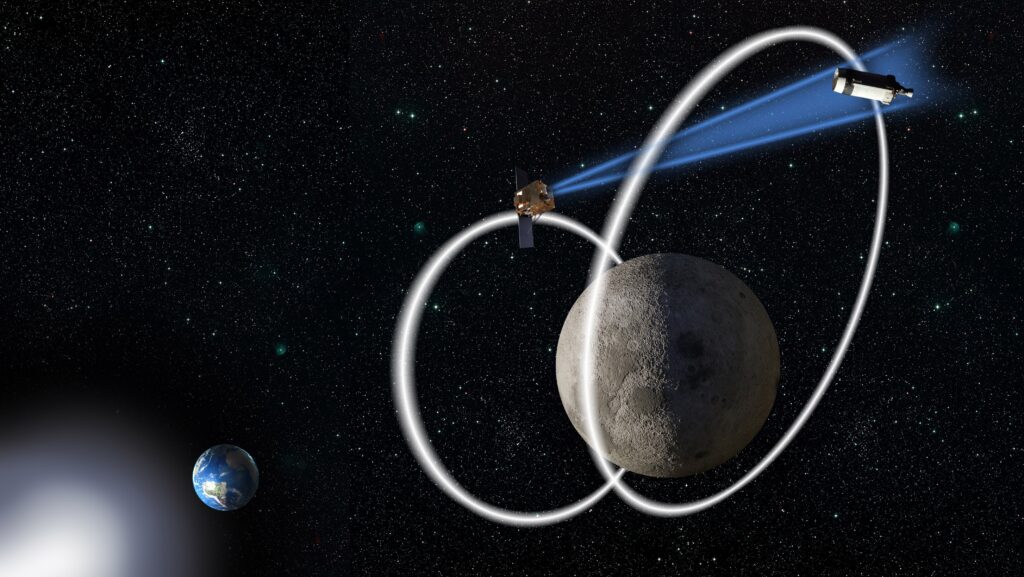

The novel satellite, called Cislunar Highway Patrol Satellite (CHPS), would be the first space domain awareness (SDA) bird to focus on cislunar space, the vast region between the Earth’s outer orbit and the Moon’s. It could also be the US military’s first attempt to operate a satellite in the special orbital domains near celestial bodies known as Lagrange Points, where a spacecraft can, in essence, ‘hover’ in a relatively fixed spot.

While AFRL has released few details about the concept up to now, including the budget, one of the areas where the program will need to push the technology envelope is in propulsion. For satellites to operate for long periods of time in lunar orbit, they will need large amounts of power and carrying vast amounts of rocket fuel is simply not feasible.

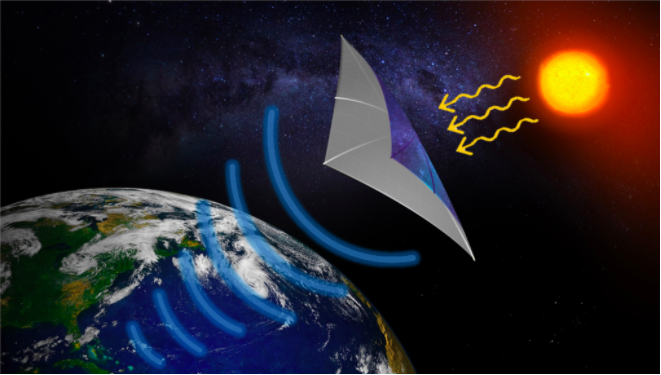

So, this is an area where another AFRL experiment, the Space Solar Power Incremental Demonstration and Research (SSPIDR) project, may come into play.

“It’s too early in the program to make decisions one way or the other, but in general AFRL is always seeking ways to make our investments interactive with each other. If it pushes the boundaries of science and technology, we will be thinking about how it might work. We will certainly have these discussions with our SSPIDR program colleagues, as they advance their solar power beaming experiments,” Buehler said.

AFRIL’s primary interest is in space-based solar power — also known as solar power satellites (SPS) — which provides energy for far-flung air bases on the ground.

“Ensuring that a forward operating base receives power is one of the most dangerous parts of a ground operation. Convoys and supply lines, which are major targets for adversaries, are the usual methods to supply power. To utilize the solar power beaming system, a service member would simply set up a rectenna to gain access to power, eliminating costly and dangerous convoys,” AFRL’s fact sheet on the SSPIDR program explains.

But the ability to collect solar energy in space, convert it to microwaves (or lasers) and beam it to collectors (batteries) for consumption also could prove critical to powering up satellites that have to travel the vast distances of cislunar space.

“Satellites and facilities in cislunar space may be the first customers of beamed power as it becomes available,” finds an Oct. 6 paper by James Vedda and Karen Jones of Aerospace Corp’s Center for Space Policy and Strategy. The paper is one of Aerospace’s ongoing Space Agenda series looking at the future of space.

“On-board solar arrays have powered spacecraft ranging in size from a couple of kilograms to the approximately 400,000-kilogram International Space Station, which produces over 100 kilowatts of power. The cost of that power is high, and the systems to produce it are a substantial portion of the mass of the spacecraft,” the paper, called “Space-Based Solar Power: A Near-Term Investment Decision,” elaborates. “Projections for the growth of cislunar activity point to commensurate growth in demand for power, and some installations could require power levels in the multi-megawatt range, far higher than any power system deployed in space thus far. SPS systems could become one possible solution to address that demand.”

DoD has shown sporadic interest in the concept for decades, funding a variety of studies, basic research and experiments. For example, besides SSPIDR, the mysterious X-37B space plane which launched on its sixth mission May 17 carried an experimental payload, called the Photovoltaic Radio-frequency Antenna Module (PRAM), designed to test converting solar radiation to microwave radiation. The module was developed by the Naval Research Laboratory.

Up to now, the US has made little progress on making space-based solar power a reality “because the technology is challenging and efforts to develop it have been inconsistent and minimally funded,” Vedda and Jones say. That may be changing, however, due to China’s ambitious plans to pioneer its use.

“China intends to become a global SPS leader and views SPS as a strategic imperative to shift from fossil based energy and foreign oil dependence. China’s SPS strategy is dual use—military and civil,” the Aerospace paper asserts. “SPS milestones include:

- 1990: Interest in SPS initiated

- 2010: Publication of an SPS roadmap

- 2019: Establishment of the first state-funded prototype SPS program

- by 2025: Demonstration of a 100 KW system in LEO

- by 2030: Plans for a 300-ton MW-level space-based solar power station”

As Breaking D readers know, military space leaders over the past year also have been gradually turning up the volume on concerns about China’s long-term lunar exploration plans. China last January became the first country to land a rover on the far side of the Moon, and to pioneer a relay satellite system in lunar orbit to allow communications with it. These concerns are the primary driver behind growing interest within the Space Force on expanding its situational awareness to cislunar space — and CHPS is the first effort to build such capabilities.

“The rise of China’s space program presents military, economic, and political challenges to the United States,” says a September study by Air University’s China Aerospace Studies Institute and CNA.

“This report concludes that the United States and China are in a long-term competition in space in which China is attempting to become a global power, in part, through the use of space. China’s primary motivation for developing space technologies is national security,” the study says.

As I reported on Tuesday, SSPIDR is finalizing it’s initial contract with Northrop Grumman and expects to take delivery of its first satellite bus, called Helios, for carrying a power-beaming experiment. AFRL intends to release details on Helios, and future plans, as early as next week. Meanwhile, testing high-strength materials that can be tightly compacted into small spaces for the SSPIDR program is the first major project for AFRL’s new Deployable Structures Laboratory (DeSel) at Kirtland AFB.