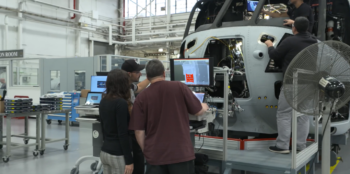

Airmen from the 4th Space Control Squadron take a picture in front of the Counter Communications System Block 10.2 on March 12, 2020 at Peterson AFB, Colorado. (U.S. Air Force/Andrew Bertain)

WASHINGTON: The Russian military’s jamming of GPS signals and communications satellites in Ukraine is considered by the US government as essentially a routine wartime activity, according to a senior State Department official.

Judging from actual real world actions during recent conflicts around the globe, Washington and Moscow appear to be on the same page with this issue — a good thing for avoiding conflict between the two nuclear powers. But there may be a growing disconnect between the two sides on the question of satellite interference outside of direct conflict, with a senior Russian official earlier this month making the surprising claim that doing so is an act of war.

During a March 17 virtual conversation at the National Security Space Association, Eric Desautels, acting deputy assistant secretary for emerging security challenges and defense policy in State’s Arms Control, Verification and Compliance bureau, explained that the US military has its own jamming capabilities for use in conflict zones.

“For example, the United States has our own communications jammer known as the CCS system,” he said. “We think that jamming is probably a normal part of conflict.”

CCS is the Space Force’s Counter Communications System, a mobile communications satellite jammer built by L3Harris and first fielded in 2004. The system has been upgraded routinely over the last 20 years, with the latest upgrade, called Block 10.2, declared operational in March 2020.

In the current conflict, Russian forces actively have been jamming GPS signals in Ukraine as they attempt to advance. In addition, a senior Ukrainian cybersecurity official this week suggested that a Feb. 24 cyber attack on commercial communications provider Viasat, which provides Internet connectivity in Ukraine and Europe, was part of an organized Russian cyber campaign against his country’s forces.

Reuters quoted Victor Zhora as saying that the attack, which shut down thousands of satellite receivers across Europe, “a really huge loss in communications in the very beginning of war.” While Zhora said the attack has yet to be formally attributed to Moscow, “we believe that Russia is attacking not just with missiles and with bombs, but with cyber weapons.”

While jamming Ukraine’s systems will certainly not be welcome by Ukraine or its supporters, it appears that in the US view, those actions are just part of any basic military engagement.

Jamming and hacking satellite capabilities in peacetime, however, is an entirely different matter — and the subject of planned UN discussions seeking to create norms for military activities in space, he said.

When employed outside a theater of conflict, the US considers satellite interference to be “irresponsible” and potentially dangerous — strong disapproval, but a far cry from calling it an act of war.

“Jamming in peacetime that disrupts activities of civilians — for example, Russia’s jamming of GPS during the Trident Juncture exercise off of Norway that caused aircraft … to be unable to use GPS — that is an irresponsible behavior,” Desautels said.

For that reason, he said, the US wants to raise the issue of jamming of GPS receivers, as well as of satellite command and control, during the upcoming meetings of the UN Open Ended Working Group (OEWG) On Reducing Space Threats. “If you lose control of your satellite, that makes it a hazard to other satellites,” he explained. “And so there’s a lot of work that can be done on all of these various cyber attack methods, jamming methods, that we look forward to having discussions on in the Open Ended Working Group.”

Peacetime (or what passes for it): Just Say No

Contrast Desautels’ remarks to those of Dmitry Rogozin, the head of Russia’s space agency Roscosmos, earlier this month, and a disconnect seems to appear.

Reuters reported on March 2 that Rogozin, who has a history of hyperbolic statements and over-the-top tweets, told Russia’s Interfax News Agency that “Offlining the satellites of any country is actually a casus belli, a cause for war.”

Up to now, there has been no indication that any country seriously considers satellite interference as a legal act of war that allows an armed response. Under international law, a casus belli is a justification that a nation is being threatened, and thus has a right to self-defense.

Instead, Russia, China, the US and Iran (and most likely others) have used GPS and/or satcom jamming for both political and military purposes in what is at least technically peacetime. (For a good primer on the extent of such activities, see Secure World Foundation’s annual Global Counterspace Capabilities report.) This suggests that nations see reversible satellite interference as acceptable under what is know as customary international law, or in essence, real-world practice.

Which is precisely why the US, and the United Kingdom that sponsored the effort to launch the OEWG, want it to be on the table during the upcoming discussions.

And as far as electronic warfare in conflict zones, Russian forces practice it routinely. The Russian military has frequently jammed GPS in Eastern Ukraine since the Crimean conflict in 2014, according to experts inside and outside the US government, as well as in Sryia.

Desautels said that the OEWG is now set to begin May 9, although it remains unclear whether it will actually happen due to the ongoing war. As Russian aircraft are now banned from landing in either the US or Europe, he explained, Moscow may try to block the meeting from going forward by arguing that Russian diplomats from the Foreign Ministry will be unable to attend.

In fact, the May 9 date for the launch of the first OEWG session is the result of Russia’s attempts to derail the talks during a preparatory meeting last month; the original plan was for Feb. 14-18 in Geneva, Switzerland. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was initiated on Feb. 23.

Desautels stressed that the OEWG discussions are important to the United States as it seeks to promote more stability in military space relations — an effort the Pentagon is fully behind.

As first reported by Breaking Defense, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin last July issued a first-ever unclassified policy memo committing the US military to five overarching “tenets” to guide DoD space operations in peacetime. And one of those tenets states: “Avoid the creation of harmful interference.”

Meanwhile the National Security Council is leading an inter-agency effort to put more flesh on the bones laid out by Austin and years of declarations by US government officials. That work, Desautels said, is still ongoing and covers a number of complex issues, such as how to ensure that any agreements don’t prevent tests of missile defense systems.

Russia and China, on the other hand, have been been less than supportive of the UN discussions, voting against the establishment of the group. That said, several Western diplomats have told Breaking Defense that Beijing has been less belligerent in the run up to the discussions (as well as parallel efforts taking place in Vienna to establish guidelines for best practices for space activities), and has shown willingness to seriously engage on the issues.

Desautels kept a hopeful tone in his remarks last week, but cautioned that the May meeting is the first in a two-year process that will run through 2023.

“This is going to be one of the first times where we really sit down with countries and start talking about these norms of responsible behavior,” he said. “So, the first meeting in May will most likely be focused very much on background information — what is the outer space environment; what are the security threats in the environment what is the existing legal regime in the environment — so that we can raise the level of education.”