SPACE SYMPOSIUM: Not only are more countries racing to develop counterspace capabilities, but the testing of anti-satellite technology has been on an upward trend in recent years, according to new, separate research by Secure World Foundation and the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

SPACE SYMPOSIUM: Not only are more countries racing to develop counterspace capabilities, but the testing of anti-satellite technology has been on an upward trend in recent years, according to new, separate research by Secure World Foundation and the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“This is a return to some of the competition and the arms racing we saw during the Cold War between the US and Soviet Union. Of course, the difference now is: there’s lots more countries involved,” said SWF’s Brian Weeden.

CSIS’s Todd Harrison agreed. In particular, he said, the use of radio frequency jamming and hacking have become practically de rigueur during political instability, pre-conflict and conflict. Harrison cited the cyber attack that US officials have blamed on the Russian military against space-based Internet provider Viasat that took out ground stations in Ukraine as a recent example.

“It has become commonplace. And I worry that that sends a message to folks that it doesn’t cross the threshold, that it’s not going to trigger any kind of response — because so far, it hasn’t really,” he said. “I think these forms of attack are increasingly viewed as something you can do with impunity.”

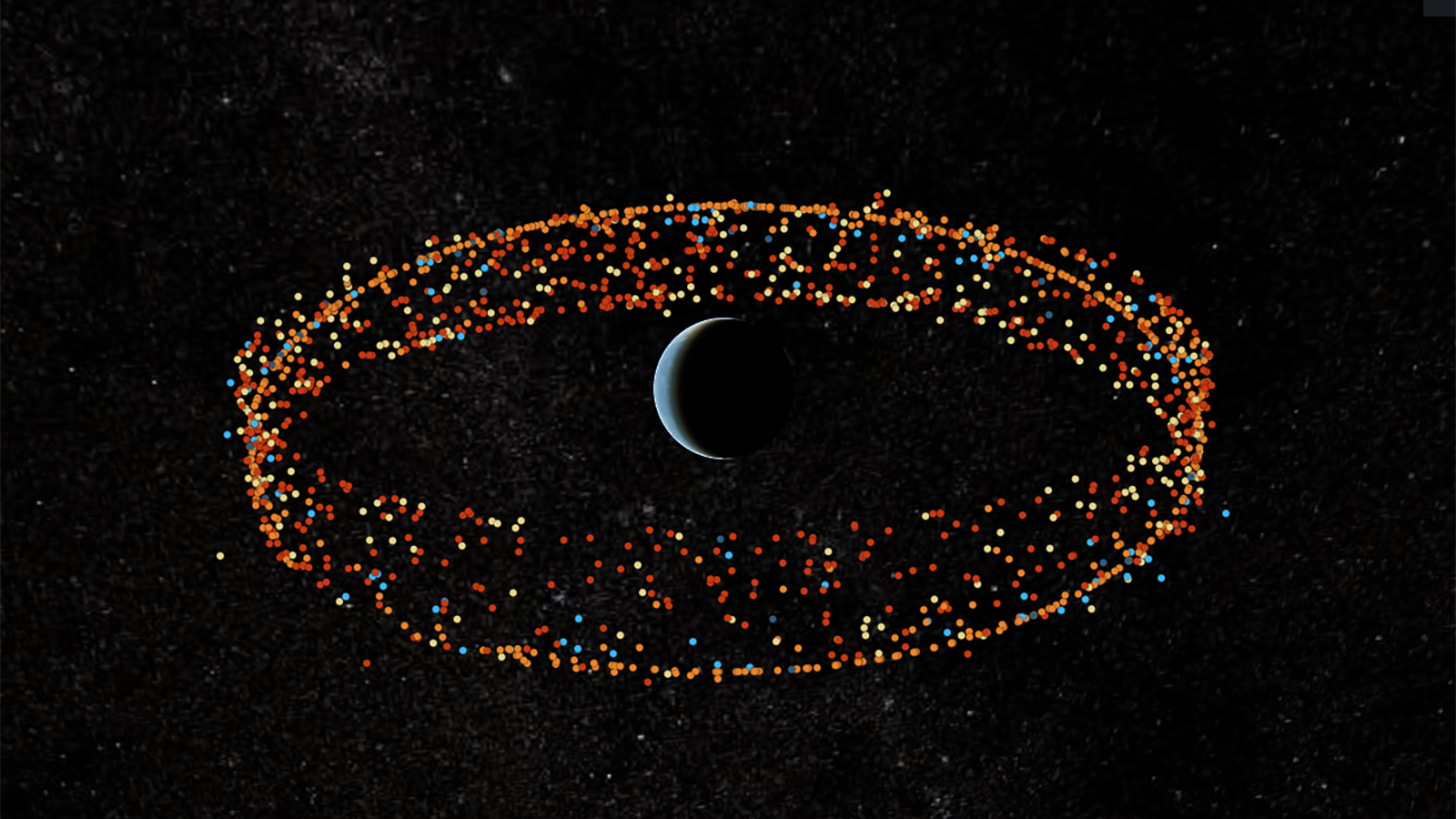

The two spoke, along with a number of their colleagues, during an April 1 briefing to reporters about their annual twin reports on counterspace activities: SWF’s “Global Counterspace Technologies” and CSIS’s “Space Threat Assessment” released today to coincide with the start of the Space Foundation’s annual Space Symposium. The two organizations, along with the University of Texas at Austin also have created a website that allows the public to track space debris, including that created by ASAT weapons tests.

Weeden said that of the “somewhere north of 70” ASAT tests in space (of various type of technology), about 50 of them took place between 1959 and 1995. Following a “brief window” of no activity, there have been another 20 or so since 2005, although he was quick to explain that both the SWF and CSIS reports rely on open sources and thus probably aren’t accounting for everything.

“None of us actually have a comprehensive set of all counterspace weapons,” agreed Harrison, “especially for the non-kinetic stuff that can’t be seen; it can’t be observed necessarily. So, I think that means it’s kind of impossible to know the total amount of anti-satellite activity that’s been going on.”

Both reports, however, agree that the trends are going in the wrong direction — that is, toward a greater probability that either military jousting in space could lead to conflict, or the space environment could be put at risk because of conflict in space.

Troubling Trend Of Countering Counterspace Weapons

One of the most worrisome trends reported by the studies is the increase in the number of countries seeking to develop counterspace capabilities, often couching that pursuit as a need to respond to potentially hostile weapons development by others with “counter-counterspace weapons.”

For example, the SWF report added three countries to its watch list on counterspace weapons development: Australia, South Korea and the United Kingdom. All three, while using careful rhetoric, “are reorganizing their militaries and military space activities to focus on space threats, and also considering their own offensive counterspace capabilities,” said Weeden.

This is in addition to the US, Russia, China, India — all of which in recent memory have conducted destructive ASAT tests on orbit — and France, Iran and North Korea.

“We see a lot of nations creating new military organizations to focus on space, and a lot of the rhetoric is on this countering counterspace activities,” said CSIS’s Kaitlyn Johnson. “They see the development of counterspace activities and the uses of them, and so now they’re structuring their own militaries to either build more resilient systems or even build counterspace weapons that the intent is for those counterspace weapons to attack other counterspace weapons.”

However, she said, in reality there isn’t any difference between a supposedly defensive counter-counterspace weapon and an offensive weapon for attacking satellites and ground stations.

“The only difference,” Johnson said, “is the intent behind it.”

The upshot, the researchers all agreed, is that as Johnson said “we’re seeing the further weaponization of the space domain without a lot of norms of behavior” which is “not a good positive norm for safety, stability and sustainability; it’s actually a really disruptive norm.”

SWF’s Victoria Samson pointed to the small silver lining in all the negative recent news: the discussion that followed a Russian ASAT test this past November that created a cloud of long-lived space debris — some of which came close to imperiling not only the multinational crew (including Russians) on the International Space Station, but also Chinese satellites and its own space station.

“It created a real situation and real circumstances, real consequences. And so a lot of countries that had been kind of on the fence about it, are now very much in support of an ASAT test moratorium. We expect that to come out when the UN has its meetings on norms of behavior for space security in Geneva, hopefully this May,” she said.

The Biden administration has signaled for months that it likely will support, even champion, such a moratorium, but Samson said there also is some hope that China too will do so because of the Russian test.

“I think China’s approach will change as well,” she said. “So there’s a very good chance that they might be able to support this sort of moratorium.”