Soldiers carry out an exercise during EDGE 22. (Courtesy of the Army’s Future Vertical Lift Cross-Functional Team)

WASHINGTON: Italian soldiers were equipped with their communications kit. Dutch soldiers brought their tactical command and control node. German soldiers operated with their own comms gear. Alongside them, US soldiers with the 82nd Airborne Division carried American networking gear.

All those systems, working and communicating together, have to transmit and integrate data seamlessly so warfighters from all the countries can jointly plan and execute operations against, say, enemy air defenses.

At a time when the US military is still learning how to share data among its own services, it seems a tall order to multiply the complexity by involving allied nations as well. But that’s the kind of international joint fighting the US Army expects in the battlefield of the future, and one they’re attempting to master, one stumbling block at a time, now.

“Part of this is just forming teams, and understanding our gaps, identifying those gaps with data collection,” Maj. Gen. Walter Rugen, director of the Future Vertical Lift Cross-Functional Team, told reporters during a media roundtable on May 13.

Beginning April 25 and over the course of nearly three weeks at Dugway Proving Ground, Utah, the US future vertical lift team got a taste of the complexity of integrating battlefield tools developed in and used by other nations, and trying share information across different security classification levels.

“[I] don’t want to oversell it. We got way more work to do than what wins we made, but those were very encouraging signs,” Rugen said.

While the Future Vertical Lift Cross-Functional Team is developing new drones and helicopters for the Army, it’s also developing the aerial network that all those capabilities will use to communicate. And as the Army — and broader US military — work toward achieving Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2), in which sensors and shooters are interconnected, experiments like the Experimentation Demonstration Gateway Event (EDGE) 22 event is key to joining those systems together.

The Army’s previous, and larger, Project Convergence experiment last fall included other American services to practice data sharing with them. The EDGE 22 experiment went further, including seven allied nations: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. During the experiment, the combined force worked together on a simulated mission find and destroy an enemy integrated air defense system in Europe. Overall, EDGE 22 had 67 technical objectives, 34 first time events and 17 distinct FVL technologies and capabilities, the Army said.

“What an opportunity like this does is illustrate the complexity of a future battlefield and help us prioritize that incremental approach,” said Brig. Gen. Rob Barrie, director of Program Executive Office Aviation. “We’re not gonna be able to do everything at once, but seeing it employed by soldiers with actual technology gives us a clearer path for how we can incrementally approach achieving this desired end state.”

Throughout the experiment, the allies operated on a “parallel” network, Rugen said, that connected with the US soldiers network in the Combined Joint Task Force tactical operations center. That allowed allies to connect to make calls for fires or medical evacuations.

In one example of improved interoperability, forces from the Netherlands integrated a command and control system into the Army’s Windows Tactical Assault Kit, which then facilitated Italian forces ability to pass on medical evacuation requests. Rugen added that the Dutch C2 system also successfully plugged into three “relevant” waveforms. In another use case, German and Italian forces equipped with their own networking gear completed a combined air assault with the 82nd Combat Aviation Brigade.

“We have many different investments we’ve already made, as well as our joint and coalition partners have already made,” said Lt. Gen. Thomas Todd, deputy commanding general for acquisition and systems at Army Futures Command. “The question in front of us is, how do we stitch them together and see ourselves?”

The 82nd Airborne Division also completed extensive work with cross-domain solutions, technology that allows data to traverse between classified and unclassified networks with security controls. For example, Rugen said the soldiers were able to receive sensitive but unclassified battlefield data, while holding back secret metadata. That kind of capability is considered a key enabler to sharing battlefield information with allied forces.

“Those cross domain solutions are gonna serve us well in future, I think, as we look at the yard International, and how we can best best in interoperate,” said Brig. Gen. Brandon Tegtmeier, the 82nd Airborne’s deputy commanding general for operations told reporters.

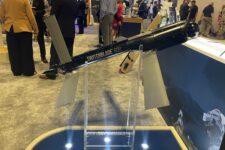

For an experiment involving the Air-Launched Effect (ALE) swarm, essentially a group of mini drones, soldiers launched four waves of seven drones. The drones were equipped with AI-enabled software to conduct reconnaissance on enemy positions that provided location data across the network back to the commander. Notably, the ALEs operated on two different waveforms, doubling the range of each drone.

The range of the drones, which can function as an ISR asset or its own explosive munition, is forcing the Army to “to make sure that our concepts align with that technology,” Rugen said. The drones need to be able to communicate at further distances, sense and operate in a contested environment.

“What we don’t want our stuff to go in and then just get jammed … and then just fall out of the sky,” Rugen said.