AUSA 2022 — All five teams competing for the Army’s next-gen troop carrier have slimmed down to smaller designs and gone to hybrid-electric drive, two generals told reporters on Tuesday.

The Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle will also have active protection against anti-tank missiles, like the Javelins and NLAWs that have decimated Russian armor in Ukraine. And OMFV will feature extensive automation (hence the name “optionally manned”), piggybacking on the progress of the wholly unmanned Robotic Combat Vehicles that troops are already testing in the field.

Together, RCV and OMFV could bring a future armored force that’s lighter, stealthier, less gas-guzzling, and less dependent on exposing human beings to enemy fire. That would make mechanized units more deployable, easier to resupply, and more effective in combat — if, of course, the technology and funding materialize on time.

RELATED: Three US Army vehicle upgrade programs look smart after Russia’s Ukraine debacle

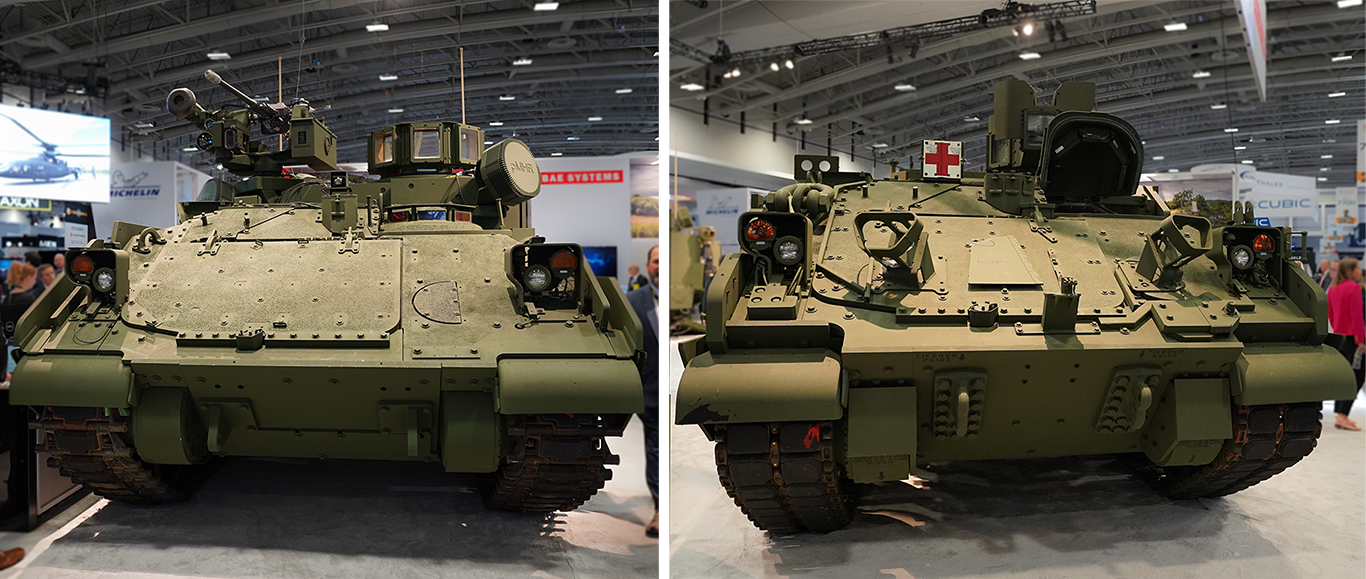

Meant to replace the M2 Bradley as the Army’s frontline armored troop carrier, or “infantry fighting vehicle,” OMFV is in Phase 2 of an innovatively structured five-part program. Five industry teams — General Dynamics, BAE Systems, Rheinmetall-Raytheon-Textron, Oshkosh-Hanwha, and Point Blank Enterprises — are currently refining virtual designs. The forthcoming phases are detailed digital design and production of physical prototypes, with final, formal proposals due Nov. 1. The Army hopes for bids from all five teams, officials said, plus potentially other companies that didn’t get Phase 2 contracts.

The five teams now on contract have gone through three rounds of refinements already, said Maj. Gen. Glenn Dean, the Army’s Program Executive Officer for Ground Combat Systems (PEO-GCS). Each cycle takes each team’s digital design, runs it through computer simulations and analysis by veteran operators, and then hands that feedback back to the companies so they can make improvements.

“We’ve gone from very large vehicles to much smaller ones along the way,” Dean told reporters at the annual Association of the US Army conference. “We’ve seen all five current participants go to hybrid electric designs, [although] each one of them is taking a different approach.” While Dean emphasized that hybrid-electric isn’t a mandatory feature of the design (i.e. it’s not a formal Army “requirement”), hybrid not only saves fuel — significantly simplifying logistics — but also runs much quieter than conventional tank engines.

All told — and in stark contrast to an earlier, since-cancelled version of OMFV that rushed to physical prototypes — the repeated cycles of digital design are allowing a lot more innovation than in traditional programs.

“We’re seeing different armor package configurations,” said Brig. Gen. Geoffrey Norman, the new director of the Next Generation Combat Vehicle Cross Functional Team (NGCV CFT). “We’re seeing different track… It’s going to result in a really transformational capability to replace the Bradley.”

Active Protection Systems

All five OMFV designs have also integrated Active Protection Systems (APS), Dean told Breaking Defense after the press conference. All five will be compatible with the Army’s standardized Vehicle Base Kit for APS, Dean added, which allows easier upgrades over time.

Active protection combines radars, jammers, and miniaturized missile defenses to blind, spoof, or in the last resort shoot down incoming rocket-propelled grenades and anti-tank missiles. While APS can’t replace conventional armor entirely — in particular, it can’t stop high-velocity cannon shells — it can significantly improve survivability for a modest increase in weight. The Army’s already integrated the Israeli Trophy APS on many of its massive M1 Abrams main battle tanks, but active protection progress has been slower on lighter vehicles that need it more.

After major delays, the M2 Bradley troop carrier, which OMFV will replace, is getting another Israeli APS, Iron Fist. “We’ve completed all the live fire testing on that, we’ve got a little documentation to update, it’s essentially ready to go — if production of it is resourced,” Dean said. “We’re not funded to actually procure.”

The turretless utility variant of the Bradley, the new Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV), does not have active protection, and as a support vehicle — with cargo, medical, mortar-carrier, and mobile command post variants, not frontline fighting vehicles — AMPV is fairly far down the priority list to get it, Dean said. The new light tank being issued to airborne troops, the Mobile Protected Firepower (MPF) system, doesn’t have APS yet either, but Dean told us the service is investigating whether to add it as a future upgrade.

That leaves the eight-wheel drive Stryker light armored vehicle, where the Army has tried and failed to integrate active protection. “That continues to be a challenge,” Dean said frankly. “We’re looking at the options and opportunities; we haven’t yet come down to a solution that strikes the balance” between being compact enough to fit on the Stryker and powerful enough to protect it well.

Stryker is relatively light and thinly armored by tank standards, although still far bigger and better protected than a Humvee. But the Army is exploring even lighter machines, ones that will protect soldiers not by having heavy armor but by having no human beings aboard: the unmanned Robotic Combat Vehicle program.

Autonomy, Robotics, & Optional Manning

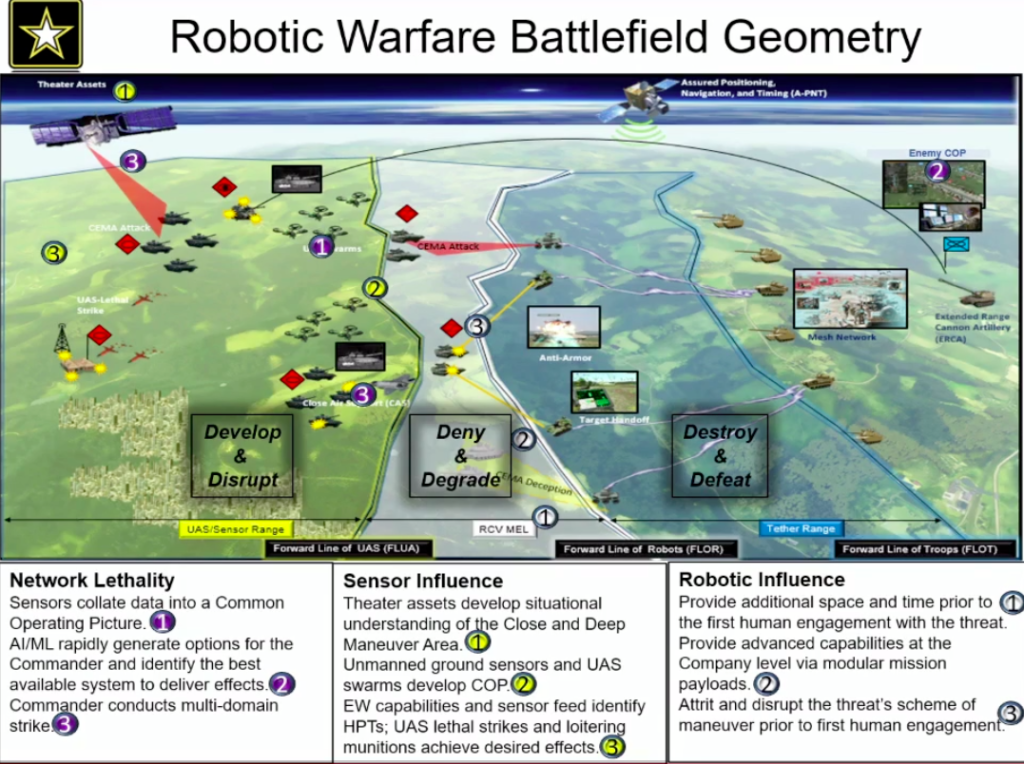

In future wars, the Army wants its manned ground vehicles accompanied into combat — or better yet, preceded — by a robotic swarm of unmanned machines. The Army already has a handful of Robotic Combat Vehicles in both RCV-Light (Qinetiq) and RCV-Medium (Textron) variants, and troops have conducted extensive experiments with them in the field.

RELATED: Green Berets, weaponized robots team up for offensive operations

“Soldiers are very excited about capabilities RCV provides to help detect enemy vehicles,” Norman told reporters. “[But] soldiers still want to be in the loop for deciding and assessing the identification of those targets or those anomalies.” It’s the difference between “target detection” and “target identification,” he said.

In other words: Troops trust the RCV to pick out potential threats and targets, but they want to double-check its work rather than just accept the algorithm’s verdict on what to shoot at. One approach Norman is considering is the Army’s experimental (and controversial) ATLAS system. ATLAS automatically detects, classifies, and prioritizes targets, highlighting them on a touchscreen interface for the gunner — but the AI itself can’t open fire because it is, quite deliberately, not connected to the firing mechanism.

Likewise, Norman continued, “soldiers are really excited about the ability of RCV to execute movement tasks — to get from Point A to Point B with little human intervention — and not quite as interested at this time in having robotic combat vehicles execute actual maneuvers.” In military terms, what most of us do all our lives is merely “movement,” navigating from place to place as efficiently as possible — something artificial intelligence is getting increasingly good at, even off-road. “Maneuver” is the art of moving across terrain under threat of enemy fire, using cover and concealment to avoid destruction — a much slower and more complicated affair that soldiers aren’t yet ready to entrust to AI.

So for the near term, at least, Robotic Combat Vehicles will be remote-controlled, with onboard autonomy handling routine tasks like driving point to point but humans controlling the sensor and weapons packages. It currently takes two humans to teleoperate one RCV. But even with these limitations, the Army is eager to get its hands on these unmanned scouts.

In 2023, “we’ll be fielding, on a limited basis, Robotic Combat Vehicle – Light,” Norman said.

It’s tricky to define that version of RCV in conventional programatic terms, but, he said, “it’s not a ‘pre-prototype,’ it’s an ‘early version’ for us to continue to do learning with.”

Over on the acquisition side, said Dean, “we’ve started the program, we’re in the requirements definition piece of that. [We] will probably have the rapid prototype final selection in the hands of soldiers about the 2025 time frame for initial testing.”

All the lessons learned, software developed, and user interfaces designed for RCV will then be available for OMFV, which is set to enter service by 2029. “A lot of the task off-loading — the things that we want autonomy to do rather than have a soldier intervention — is the same for a Robotic Combat Vehicle as it would be for an Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle,” said Norman.

The goal is to develop a library of algorithmic “behaviors” that can be used by a wide range of vehicles, said Michael Cadieux, director of the Army’s Ground Vehicle Systems Center (GVSC), in a briefing for contractors and other attendees at AUSA. Sharing those algorithms — and rapidly updating them as different companies come up with new and better ideas — requires an approach called open architecture, where the Army enforces common standards on all vendors, so their products all work together, but gives each vendor wide leeway to innovate within those standards. “[With] the architecture today,” Cadieux admitted, “there’s absolutely areas where it’s not open enough” — but the Army’s working to open it up.

The OMFV will be entirely based on open-architecture standards, both Norman and Dean emphasized, to allow compatibility across subsystems and easier upgrades.

That means the optionally-manned vehicle can benefit from all the research, development, and experimentation on the unmanned one. The difference is that the OMFV will carry six infantry soldiers in back and be operated by three human crew — which is planned to drop to two over time as autonomy improves.