An XQ-58A Valkyrie launches at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground, Ariz., Dec. 9, 2020. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Joshua King)

The value of relatively low-cost unmanned aerial vehicles has become clearer by the day in Ukraine, causing war strategists to rethink their usefulness elsewhere. In the op-ed below, RAND Corporation’s David Ochmanek argues a recent move to pull F-15s out of an American base in Japan is a perfect opportunity for rethinking the military’s posture there — and where drones might fit in.

The US Air Force recently announced that it plans to withdraw its force of F-15C/D fighter aircraft from their home at Kadena Airbase in Okinawa. While the immediate strategic implications may be debatable, the announcement highlights both the need and the opportunity for the Air Force to revamp its force posture in the Western Pacific and elsewhere. Analysis suggests a relatively new technology could play a major role in any future posture: autonomous, runway-independent air vehicles.

Given that the National Defense Strategy has placed top priority on deterring aggression by China, subtracting combat aircraft based in a front-line allied nation seems counter-intuitive, and it reflects some of the dilemmas facing the Air Force as it tries to manage an aging and shrinking fleet of fighters.

The F-15s are among the oldest fighters in the USAF’s inventory, and the service announced that for the time being it plans to offset their withdrawal from Kadena with rotational deployments of more modern fighters. But sustaining a rotational presence on Okinawa could add to the stress on a force that has, for many years now, been hard-pressed to meet demands for fighter presence elsewhere in Asia, Europe and the Middle East.

RELATED: Is an ‘epoch-making’ agreement between Australia and Japan in the works?

Longer-term options currently under consideration include re-establishing forward stationed fighter squadrons at Kadena with fifth-generation fighters or growing the overall size of the USAF’s fighter fleet to support rotational deployments. But these options lack a supplemental dash of creativity, considering the strategic need to be fulfilled.

The first question that may need to be addressed concerns the viability of Okinawa and other forward locations as loci for operations of land-based aircraft. On the one hand, Okinawa is an attractive hub for air operations in defense of Japan or Taiwan because of its proximity to the area of operations. Fighter aircraft have limited range, such that without aerial refueling, their combat radius extends only 500 miles or so from their bases.

However, Okinawa is also within range of numerous Chinese ballistic and cruise missile systems. In a war, the Chinese would be able to devote many hundreds of missiles to the task of destroying parked aircraft, runways, fuel storage and other targets associated with US and Japanese air forces on the island. Attacks on this scale could overwhelm active defenses, such as Patriot surface-to-air missiles. China wields the most potent threat, but US and allied air forces face similar threats from Russia, North Korea and even Iran.

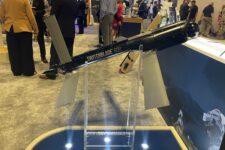

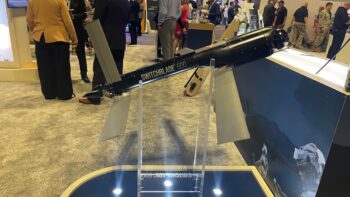

For this reason, the USAF has been experimenting with one solution that could solve two problems: the necessity of a runway and the high cost of losing the aircraft to enemy fire. Namely, the service is looking at unmanned aircraft that can be launched, recovered, serviced and re-launched without reliance on runways or other fixed facilities. The XQ-58 Valkyrie is representative of this new class of air vehicles termed low-cost, attritable aircraft technologies (LCAATs).

The XQ-58, which has made several successful test flights, is launched from a trailer with small, disposable rocket motors. Its turbofan engine then sustains its flight. A derivative of this test article could have a payload of air-to-surface or air-to-air weapons in excess of 1,000 pounds and a combat radius greater than 2,000 nautical miles.

On returning from its mission, it lands with a parachute. Mobile teams can then refuel, rearm, and relaunch the aircraft. By freeing airpower from its dependence on fixed infrastructure, this concept might largely nullify US adversaries’ massive investments in conventional ballistic and cruise missiles. (The Marine Corps’ F-35B, which can take off and land vertically, offers similar advantages.)

The other attractive feature of the LCAAT is cost: For the price of procuring the 18 F-35s that would constitute a deployed squadron, the Air Force could buy more than 300 LCAATs and support equipment. A modest number of these could be used in peacetime to supplement manned fighter operations in forward areas, but most would be stored, like munitions, in warehouses and dispersed into the field when needed.

The LCAAT is not a stealthy, high-performance aircraft. It will not be as survivable or versatile as state-of-the-art fighters such as the F-22 or F-35. But by exploiting the tactics of mass, families of runway-independent aircraft such as the LCAAT could overwhelm enemy defenses, supporting attacks by other types of standoff weapons and manned fighters.

In sum, as it considers its future force mix and posture in the Indo-Pacific region and elsewhere, the Air Force today has options that go beyond traditional platforms. Among them are rapidly maturing concepts for generating and sustaining high-tempo operations in forward areas with autonomous, runway-independent air vehicles.

David Ochmanek is a senior international/defense researcher at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation.