A “Project Origin” Robotic Combat Vehicle surrogate conducts a live-fire exercise in 2021. (Army photo)

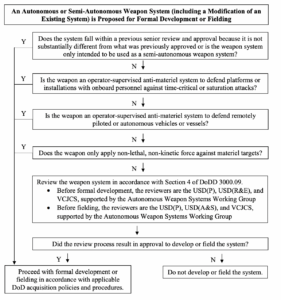

WASHINGTON — To defense officials working on robotic weapons, at first glance the recent rewrite of the Pentagon policy on “Autonomy in Weapons Systems” [PDF] might look intimidating, like a Terminator. What was 15 pages in its original form expands to 24, adding paragraphs of ethical principles that new weapons programs must abide by, a full-page flowchart of go/no-go decisions that officials must work through, and a new bureaucratic entity to oversee it all, the Autonomous Weapon Systems Working Group.

But advocates and experts told Breaking Defense the revised policy is really more like R2-D2, helpful and full of nifty tricks. By adding clarifications, the handy flowchart, and the working group as a central clearinghouse — while not actually imposing any major new limitations on the development of autonomous weapons — the 2023 revision of DoD Directive 3000.09 turns the amorphous review process first laid out in 2012 into a clear procedure you can actually do.

“On one hand, it sounds like this is adding more layers of control and regulation, and that might sound daunting,” said Michael Klare, a senior visiting fellow at the Arms Control Association. “On the other hand, I think it’s meant to give a green light to commanders and project managers, [because] they can proceed with a clear understanding of what they’re going to have to go through and what criteria they’re going to have to satisfy.”

“Under the earlier directive, there was more ambiguity,” he said. “It makes it easier.”

So far, it’s unclear if the Pentagon has ever actually had an automated weapon system go through the review process.In 2019, a spokesperson told Breaking Defense that “to date, no weapon has been required to undergo the Senior Review in accordance with DOD Directive 3000.09.” That implies one of two things: Either no proposed program has had the combination of characteristics — chiefly, both a high degree of autonomy and the potential to kill — that triggers the review, or any such program has been granted a waiver from going the review process in the first place. The policy, in both new and old versions, explicitly says the Deputy Secretary of Defense can waive most aspects of the review “in cases of urgent military need.”

Decision-making flowchart for autonomous weapons program, from the 2023 revision of DoD Directive 3000.09. (DoD graphic)

Recent statements from the Pentagon have been more ambiguous, however. In a Jan. 30 briefing for groups affiliated with the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, the organization’s founding coordinator, Mary Wareham, said the Pentagon said told the group it couldn’t comment on specific weapons when asked about the historical use of the process. That’s a stark contrast to the clarity of the 2019 statement. The Pentagon has yet to respond to Breaking Defense’s renewed questions about the policy.

In any case, despite the bureaucratic hoops, the revised 3000.09 clarifies the process of getting approval to develop and deploy autonomous weapons in a way that makes it easier, not harder, the experts said. That’s great news if you’re worried first and foremost about the US military falling behind AI and robotics efforts in Russia and China. It’s less great if your primary concern is arms control.

RELATED: Regulate military use of emerging tech before ‘Armageddon,’ new report urges

“It’s not a policy of self-restraint,” said Wareham. “The directive facilitates US development of autonomous weapons systems, as long as it’s done in accordance with existing legal rules and ethical principles. The directive does nothing to curb proliferation.”

“The old directive basically [said], in order to get approval for certain systems, you had to go through this review process, but it didn’t explain how to do the process,” said Paul Scharre, director of studies at the Center for a New American Security and longtime advocate of military drones and AI. “It wasn’t necessarily clear what to do, who do I talk to, how do I instigate this process.”

The revised directive, he told Breaking Defense, “is putting in place the mechanics to actually execute these review processes.” (Scharre has posted a line-by-line analysis of the changes in the new version).

In a January briefing for reporters, the Pentagon’s director of “emerging capabilities policy,” Michael Horowitz, downplayed what he called “relatively minor clarifications and refinements” to the original 2012 version of DODD 3000.09.

“It had been 10 years since its publication and the department is obligated every 10 years to reissue, update or cancel directives,” Horowitz said. “The release here was driven by the timelines of DoD bureaucracy.”

Horowitz was also candid about what the policy does not cover. “The directive does not prohibit the development of any particular weapon system,” he said.

It also “to be clear, does not, does not, cover S&T,” he continued. That’s the Science & Technology phase of lab work, pre-prototypes, and field experiments, and even the most advanced autonomous weapons programs are still in the experimental stage, like the Air Force’s Collaborative Combat Aircraft or the Navy’s Sea Hunter and Overlord unmanned ships.

Before a weapons program can move out of S&T, however, the policy in both the original and revised forms “requires two levels of review,” Horowitz explained: “One review prior to the beginning of formal development” — what the Pentagon calls Milestone B — “and the other prior to fielding.” Again, although Horowitz didn’t mention it, the Deputy Secretary may waive either or both reviews “in cases of urgent military need.”

The revised Directive 3000.09 incorporates the text of the AI ethics principles the Pentagon adopted in 2020 nd requires adherence to the Responsible AI Strategy & Implementation Policy issued last June. The ethics principles require all AI programs to be “responsible,” “equitable,” “traceable,” “reliable” and “governable” — in brief, that they’re not black boxes that produce the biased or outright false results that machine-learning algorithms like ChatGPT have become infamous for. The strategy then tries to turn those principles into evaluation criteria, research priorities and even reusable, reliable code. (It’s worth noting that “AI” and “autonomy” aren’t synonymous: Not all, or even most, autonomy is full-fledged AI).

The revised directive also updates the responsibilities of various officials, since the Undersecretariat of Acquisition, Technology, & Logistics was split in two in 2018. Perhaps most significant, from the bureaucratic point of view, is the creation of a permanent working group to advise the top officials on how to actually conduct the reviews.

That kind of staffing is essential to a smoothly functioning bureaucratic process, said Zachary Kallenborn, a policy fellow at George Mason University. “It depends a lot on who ends up sitting on the working group and how it’s used, but it seems useful, [because] the policy issues involved are quite complex, they’re highly technical, and often very context dependent,” he told Breaking Defense. “How does the risk and defensive value differ between an undersea, submarine-hunting drone, DARPA’s massive swarm-of-swarms, and Spot, the cannon-toting robo-dog?”

It’s actually now easier to develop Spot the lethal robot, Kallenborn said, because of some subtle additions in the revised Directive 3000.09. The 2023 version says that self-defense systems protecting unmanned vehicles are exempted from review, as long as they’re targeting equipment and not personnel: “Weapon systems that do not require the senior review [include] Operator-supervised autonomous weapon systems used to select and engage materiel targets for defending operationally deployed remotely piloted or autonomous vehicles and/or vessels,” it says.

A biological security dog poses next to a robotic one at Tyndall Air Force Base in 2021. (U.S. Air Force photo by Airman 1st Class Anabel Del Valle)

“That’s interesting and definitely makes autonomous weapon use much easier in general,” he said. “The word ‘defending’ is doing a ton of work. If a drone is operating in enemy territory, almost any weapon could be construed as ‘defending’ the platform. A robo-dog carrying supplies could be attacked, so giving Spot an autonomous cannon to defend himself would not require senior approvals. If Spot happens to wander near an enemy tank formation, Spot could fight — so long as Spot doesn’t target humans.”

Of course, enemy tanks tend to have human beings inside. “There’s a lot of vagueness there,” Kallenborn said.

The revised directive also eases development of other kinds of autonomous weapons, Paul Scharre said. For example, anti-aircraft/anti-missile systems like the Army’s Patriot and the Navy’s Aegis often have a fully automated mode for use against massive salvos of fast-moving threats. In essence, the overwhelmed human operator tells the computer to pick its own targets and fire at will, faster than a human can manage. In both the 2012 and 2023 versions of Directive 3000.09, such autonomous defenses against “time-critical or saturation attacks” are exempt from review. But the 2023 update extends this exemption to “networked defense where the autonomous weapon system is not co-located.”

In other words, the human supervisor and the autonomous defense system no longer have to be in the same place. That’s in line with the Pentagon’s push to decentralize its defenses and run widely dispersed weapons over a network. Under the new rule, if the network goes down, the remote operator can’t see what’s going on or give orders, and no human supervisor is on site, the weapon is still allowed to fire. That could save lives if the enemy jams or hacks American networks before a missile attack — or cost lives if there’s a technical glitch and the system goes off in error, as Patriot launchers did in 2003.

From an arms control perspective, Wareham said of the revised policy, “it’s not an adequate response.”

Lockheed wins competition to build next-gen interceptor

The Missile Defense Agency recently accelerated plans to pick a winning vendor, a decision previously planned for next year.