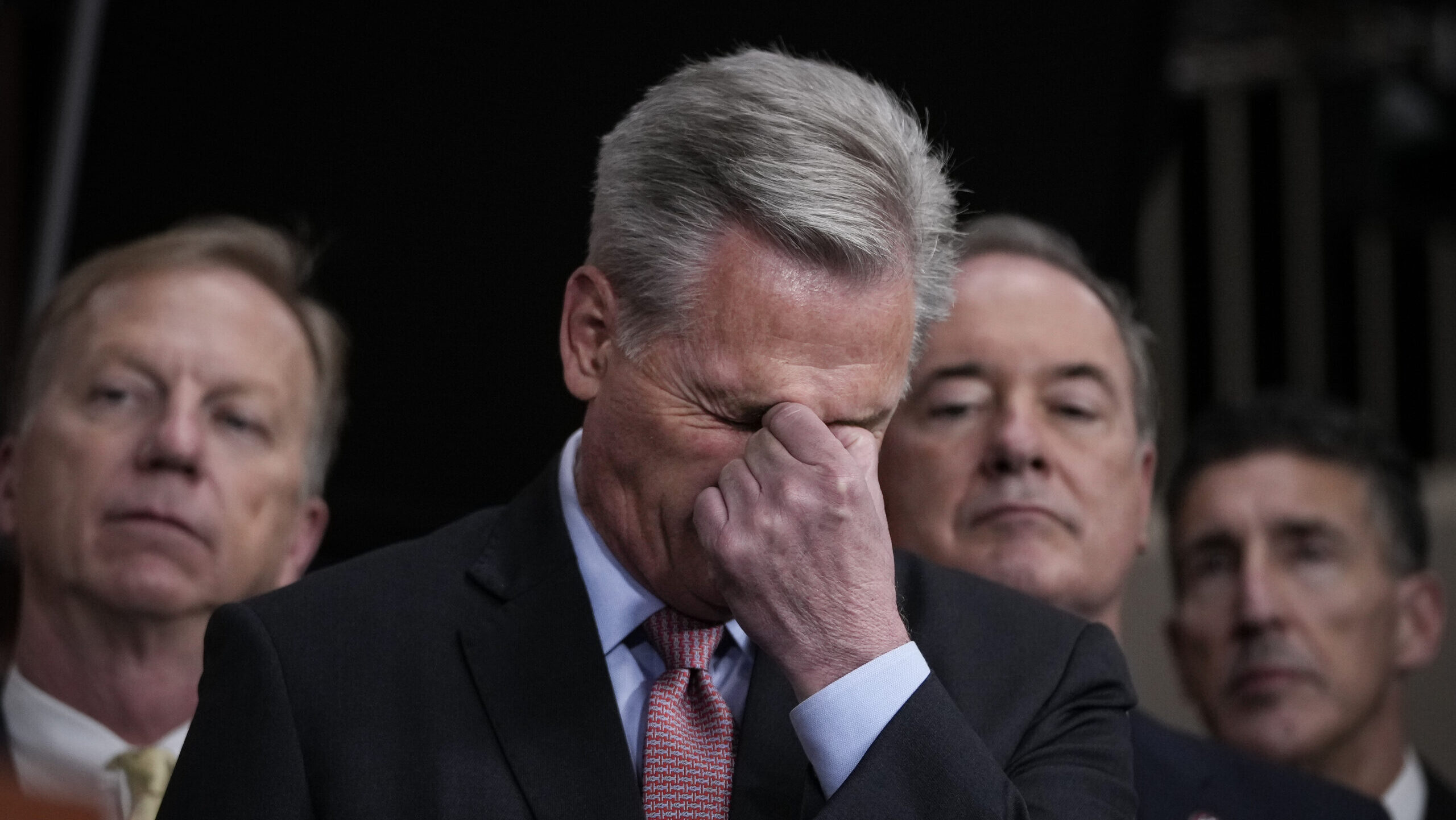

House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) attends at a news conference with fellow House Republicans at the US Capitol on January 20, 2022, in Washington, DC. McCarthy is fighting against his own caucus in order to try and avoid a government shutdown. (Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Editor’s note: As of Friday at 3 pm Washington time, a government shutdown appears all but guaranteed. As a result, Breaking Defense is re-upping our preview of what a shutdown means for the US defense community. The original story, published the morning of Sept. 27, appears below.

WASHINGTON — With four days left in the fiscal year, the mood around Washington has grimly settled into a consensus that a government shutdown is imminent.

The Senate on Tuesday passed legislation paving the way for a continuing resolution (CR) through Nov. 17 — a funding mechanism that keeps the government open at the previous fiscal year’s budget. But getting it in place would require assistance from the House, which remains effectively stalled due to a handful of Republican holdouts, whom Speaker Kevin McCarthy last week described as just wanting “to burn the whole place down.” (Those holdouts, in turn, may seek to remove McCarthy from his position.)

The political circus, of course, has consequences far beyond the halls of Congress, including inside the defense establishment. That national defense advocates are left hoping for a CR, usually described as a negative outcome, is a sign of the political reality now facing both the military and defense industry. And when it comes to the impact, Bill LaPlante, the undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment, on Tuesday summed up the situation thusly: “They’re both bad, [but] one is real bad, one’s just-so bad.”

Here’s what could come next, from disruptions to space programs to foreign weapon sales to the lives of hundreds of thousands of servicemembers and contractors:

Foreign Defense Aid, Military Pay, Civilian Jobs And Weapons Impact

Pentagon spokeswoman Sabrina Singh was direct on Monday: “The shutdown is the worst thing that could happen. We’re hoping that Congress can find a way to avert that, but, you know, [we’re] planning for the worst.”

If the government shuts down, LaPlante said, “Testing will stop. Acceptance by the government of equipment, when it is finished or ready to be accepted, can stop.” He recalled being the Air Force acquisition head in 2013 during another shutdown, and having to send all the officials home from the Defense Contracting Management Agency, who qualify new production items for intake to the military, which essentially shut down the F-35 and munition line production.

Without going into details, LaPlante also said he has “some testing we want to do next week on an item for Ukraine” that would be shut down. However, broad support for Ukraine, like training, is expected to continue, with Sing confirming it is specifically exempted under a government shutdown. As for America’s support for Taiwan against a potential Chinese invasion, US State Department officials told lawmakers last week that a shutdown would halt all licensing to Taiwan of US defense articles and would pause the process through which Taiwan can buy American arms.

For military members, the Pentagon still expects everyone to come to work — with or without pay, although in past shutdowns legislation has been passed to keep money coming in for uniformed personnel.

Sen. Roger Wicker, R-Miss., the ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, on Tuesday put forth legislation along with a number of Republican co-sponsors that would “appropriate funds to pay members of the armed forces, including reservists, if a temporary or full-year federal funding bill is not passed and signed by October 1.” Rep. Jen Kiggans, R-VA., a retired Navy pilot, introduced similar language in the House last week, but it is unclear when or if Congress can reconcile the two efforts.

Wicker’s proposal “would also fund the pay of civilian Department of Defense (DOD) and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) personnel and contractors whom each department’s respective secretary determines are ‘providing support to members of the Armed Forces.’”

According to analyst Jim McAleese, under current guidance from DoD, around 45 percent of the civilian workforce — around 365,500 people — are believed to be exempt from furloughs due to either being deemed vital workers or not being funded by annual appropriations.

US Army soldiers from the1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division conduct training at Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti, Jan. 10, 2017. (US Air Force/ Staff Sgt. Kenneth Norman)

Still, the workforce impacts, LaPlante added, are longstanding. “We’re sending people who are engineers, our acquisition professionals, our sustainers, our contracting officers, we’re just sending them home and saying, ‘you’re not essential.’ It’s just, it’s just horrible. There’s really nothing good you can say about it.”

Those workforce concerns were echoed by Doug Bush, the Army acquisition head, in a roundtable with reporters last week.

“I think my main concern, other than just the impact on the workforce in terms of disrupting people’s lives and potentially their income, would be the contracting workforce,” Bush said. “The contracting workforce isn’t that big, and it’s kind of like a factory. And a lot of those people, if we didn’t have them able to come into work as much as they can now, that could just kind of affect overall throughput on contracting, which would affect everything in some way.”

Eric Fanning, who was deputy secretary of the Air Force during the same shutdown LaPlante talked about, is now the head of the Aerospace Industries Association. In a Tuesday letter, he also warned that a shutdown would “exacerbate the cash crunch facing American businesses,” while also raising concerns about workforce impact.

“If we are unable to hire and keep our most talented workforce, we will lose our ability to out-innovate and out-perform our adversaries,” Fanning wrote. “While federal employees will return to work and likely receive pay for lost wages following the reopening of the government, contractors are not afforded the same. Instead, we are forced to turn internally and cut costs through hiring freezes, increasing the cost of products, layoffs and furloughs, or a combination to avoid significant economic impact.”

People aside, Byron Callan, an analyst with Capital Alpha Partners, said he thinks that near-term industry bottom lines should be fine — though he cautions against “assuming that the 2013 shutdown is a good template for how defense could fare,” given the political environment.

“We reiterate that a federal shutdown lasting until mid-October is not apt to materially change public company defense financials, though it might stress smaller private contractors,” Callan wrote in a note to investors Tuesday. “If there is a shutdown that starts Oct. 1, there should be enough time over the balance of the quarter to make up work that was delayed.”

Acquisition Projects Facing Risks From Shutdown

According to McAleese, multi-year deals approved from fiscal 2023 money — including from enacted $140 billion FY23 research and development funds, $164 billion FY23 DoD procurement and $19.1 billion FY23 military construction — can still be used towards new contracts. And any existing contracts that are already funded through FY23 operation and maintenance accounts can continue.

But awarding new contracts for advancing programs could become tricky, and the longer the shutdown goes on, the longer a backlog of work becomes.

Space Force: Given its focus on restructuring its development portfolio to speed fielding of new capabilities, the Space Force may well be the service most broadly affected by the shutdown.

For example, the Space Development Agency — by design, scheduled to deliver new technology improvements every two years — has been planning to announce awards next month for what the agency calls the “Alpha variant” of the Transport Layer’s Tranche 2. The Tranche 2 constellation, expected to begin launching in September 2026, would allow SDA’s mesh network of communications satellites in low Earth orbit to be accessed anywhere on the globe.

It also is expected in October to enter into source selection for Tranche 2 of its Tracking Layer of ballistic and hypersonic missile warning constellations, given that industry has been asked to submit proposals by Oct. 6.

In response to questions from Breaking Defense, SDA referred to remarks by Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall in his Sept. 11 keynote to the annual Air Force Association conference, asking Congress to avoid a readiness-damaging shutdown. Likewise, a Space Force spokesperson said the service could not comment on a prospective government shutdown and referred inquiries to the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

Air Force: Lt. Gen. Richard Moore, Air Force deputy chief of staff for plans and programs, told Breaking Defense recently that “essential services certainly keep going” under a shut down “but where we face the greatest risk” is “our ability to start and sustain modernization programs.” Moore then added, “We ought not cede any time to our adversary. We ought to make use of every single day that we have to modernize. And a government shutdown is exactly the opposite of that.”

Some of the Air Force’s key modernization initiatives could be at risk under a shutdown, including the service’s pivot to the Indo-Pacific through its Agile Combat Employment (ACE) initiative. Through ACE, operations are planned to be more dispersed using a hub-and-spoke model to prevent a crippled base from kneecapping regional operations, but the idea requires funding — funding that would be delayed by a CR or a shutdown.

The Air Force is requesting about $1.2 billion in FY24 for its ACE initiatives, which Pacific Air Forces Commander Gen. Kenneth Wilsbach recently said includes critical money for construction and pre-positioning of equipment. The FY24 budget also funds important munitions, Wilsbach said.

In a recent interview with Breaking Defense, the Air Force’s acquisition chief said space programs would likely be top priorities in need of new funding in FY24, though the service’s plans for its next-gen tanker would also suffer under budget delays. While those comments were more specific to a continuing resolution, they would be doubly true under a shutdown.

Optical links will connect SDA’s Transport Layer to weapons platforms. (SDA)

Navy: A spokesman for the Navy’s senior acquisition executive did not respond to a question by press time about the programmatic impacts of a government shutdown.

But the Navy’s No. 1 acquisition priority, the Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine, would surely be at the top of mind for service leadership. Any time there is a risk of a lapse in funding, the Navy regularly implores Congress to grant it special permissions, also called “anomalies,” to continue funding the program as normal to avoid eroding any of its infamously thin schedule margin.

By extension, the fast attack Virginia-class submarine program would also likely be at risk during a government shutdown because its supply chain is heavily interwoven with that of Columbia. If one program falters, the other usually feels an effect.

Army: Among the impact identified by the Army are a pause in some training and education activities, as well as a failure to execute on new contracts.

Asked for formal comment, an Army spokesperson said, “Like continuing resolutions, a lapse in appropriations would be highly disruptive, causing inefficiencies, units to forego training because of funding uncertainty, and much additional work. The longer the lapse, the greater the severity and impact would be on the Army’s ability to make necessary funding alignments and adjustments, avoid surge spending and respond to emerging operational requirements.”

In terms of impact on procurement, Bush, the Army acquisition chief, was a little more sanguine, saying, “I hate to say this, but it does depend on the length of a potential, I believe the formal term is, lapse of appropriations. But in terms of actual programmatics, we often don’t plan for first quarter awards — major awards — because of the potential of a CR or in this case, a shutdown.”

What Comes Next With Appropriations

Even if Congress is able to put together a last-minute CR and avoid a shutdown, the potential chaos will only be kicked down the road, not dealt with entirely.

The state of defense appropriations is extremely unclear, as the Republican holdouts in the House twice managed to scuttle a basic approval to start debate on the defense appropriations language. While that rule did finally pass on Tuesday, that still leaves major debate in the House over the appropriations language. And anything that comes out of the House will then have to reconcile with the Senate, where Democrats are unlikely to agree with conservative riders or, potentially, efforts to drop spending levels below the debt ceiling caps.

“What matters is whether Congress can pass all appropriations bills before Jan. 1 and then Apr. 30 when the Fiscal Responsibility Act stipulates that appropriations will be 99% of FY23 base budget levels,” Callan wrote to investors. “We expect if Congress has not passed all appropriations bills by Jan. 1, DoD and other federal departments and agencies will operate under the assumption that appropriations will be at the lower level (99% of FY23). That’s the prudent thing to do given what’s been on display so far in 2023 on FY24 appropriations.”

In other words, the shutdown is a major potential disruptor — but in some ways, only the first step in getting FY24 money sorted.

As LaPlante dryly noted, China doesn’t go through this kind of budget chaos. “We can teach them how to do that. That would be helpful,” he said.

Reporting by Breaking Defense’s Theresa Hitchens, Justin Katz, Aaron Mehta, Michael Marrow, and Ashley Roque.