Lockheed Martin In-space Upgrade Satellite System (LINUSS) is a pair of CubeSats testing algorithms to enable highly precise maneuvering. (Lockheed Martin)

AMOS 2023 — As Pentagon and commercial interest grows in satellites and spacecraft that can maneuver more rapidly and more often, a new industry study shows that such moves are very difficult to accurately track — leading to erroneous assessments of spacecraft whereabouts and thus increasing risks of on-orbit crashes.

“Maneuvers are the biggest cause of accuracy degradation in SSA [space situational awareness] and space domain awareness, the biggest, number one cause,” Dan Oltrogge, chief scientist at COMSPOC Corp., told Breaking Defense in an interview at the annual Advanced Maui Optical and Space Surveillance Conference in Hawaii.

For the non-cognescenti, SSA refers to being able to detect and track objects on orbit, whereas space domain awareness is the term used by the Defense Department, and increasingly other militaries, to refer to the ability to not just track, but also characterize the functions of, and determine the possible threat from, space objects.

The study, released today, examined tracking data provided by private companies as well as the US military and was conducted jointly by COMSPOC, the Center for Space Standards and Innovation, LSAS Tec, the Space Data Association, Intelsat and SES.

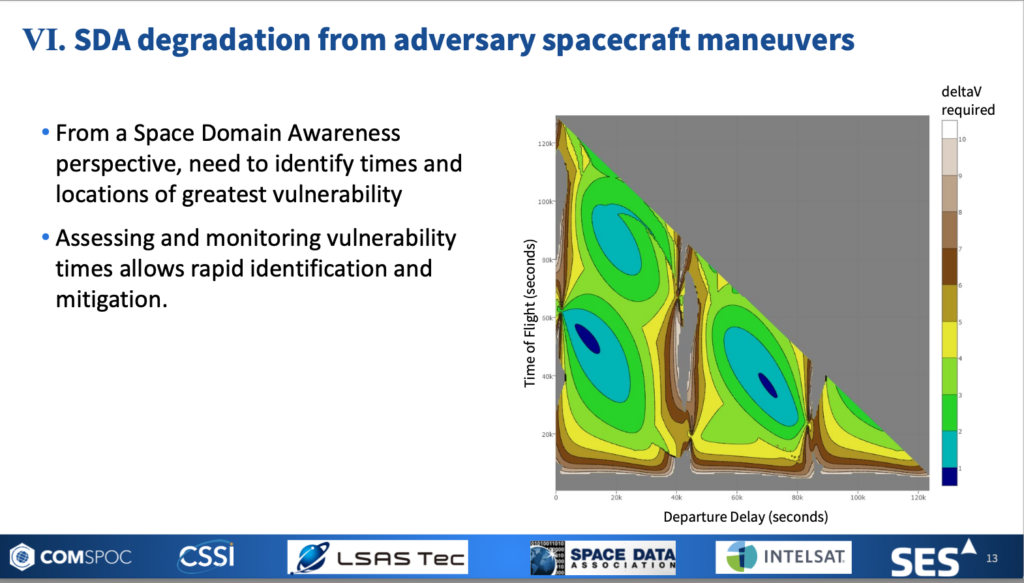

It looked at six categories of degradation in the accuracy of orbital tracking caused by maneuvers, including the risks from unannounced rendezvous and proximity operations — such as those being routinely performed by the Russian “inspector” satellite Luch/Olymp that have raised hackles at the Defense Department.

The study also looked at vulnerabilities to Space Force and US Space Command satellites caused by mis-plotting movements of adversary satellites. Being able predict where an adversary satellite is moving to in a timely manner means being able to assess whether it is on a path that threatens a US bird, and gives US operators the chance to do their own maneuvers to get out of the way, Oltrogge explained.

Oltrogge said that Luch in particular “has flown next to and snuggled up close enough to detect a signal” from a number of US satellites — in one case getting so close to an Intelsat bird that even a small change in the velocity of either of the satellites could have resulted in a crash. Further, he added, the Russians do not notify the operators of the satellites being orbited by Luch about its planned moves.

Slides presented here by the study team explained that the errors introduced by the inability to both properly track spacecraft moves and, more importantly, model the resulting change in a satellite’s future trajectory have resulted in the space tracking data produced by the Space Force’s 18th Space Defense Squadron sometimes purportedly being off by vast distances. In one instance, COMPSOC said the mismatch between where the satellite actually was after it moved to where the military trackers said it should be differed by more than 5,000 kilometers (3,000 miles). (A spokesperson for Space Force declined to comment ahead of the report’s public release, but senior officials have previously acknowledged their tracking systems are “lagging.”)

“Sometimes people assert that maneuvering objects are a very small portion of the [Space Force’s space object] catalog and maneuvers therefore are a tiny part of the problem,” Oltrogge said. “While somewhat true, note that an adversary’s dream scenario is when you assume that one of their objects is debris and therefore can’t maneuver, and … you lose track of it.”

The study identified six ways to help resolve the maneuvering problem for satellite trackers:

- Sharing of ephemerides [position at any one time], maneuver plans, astrometric observations, and spacecraft characteristics by spacecraft operators.

- Incorporation of commercial SSA and government observational data.

- Curation and fusion of such data by commercial SSA.

- Orbit determination algorithms that recover quickly from maneuvers.

- Orbit propagation tools that can predict through planned maneuvers.

- Data sharing standards development and widespread adoption.

“The bottom line of this is: You can throw as much data as you want at this problem, but people who are working on space traffic management, also need to have better inputs into modeling and better modeling,” Oltrogge said.

But even more importantly, he stressed, that the problems related to keeping tabs on maneuvering spacecraft cannot be fixed without much closer, more frequent collaboration between operators and trackers — a sentiment echoed by other space scientists and operators.

In a blog post on Monday, the Space Data Association — a consortium of 30 spacecraft operators that includes NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration that already share the whereabouts of their satellites and information about potential collision threats — said “closer collaboration between all interested parties” is necessary to improving space traffic management.

In particular, Oltrogge said, spacecraft operators need to share their planned maneuvers with each other as well as governments doing space tracking in order to assure the safety of all.

Matt Hedjuk, who works for The Aerospace Corporation and also is the chief engineer for the Satellite Conjunction Analysis and Risk Assessment (CARA) project for NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, agreed.

Sharing maneuver plans would result in “a huge improvement” to the accuracy of current space tracking, he told Breaking Defense on Monday, and is “probably the single simplest thing … that would move the needle the most.”