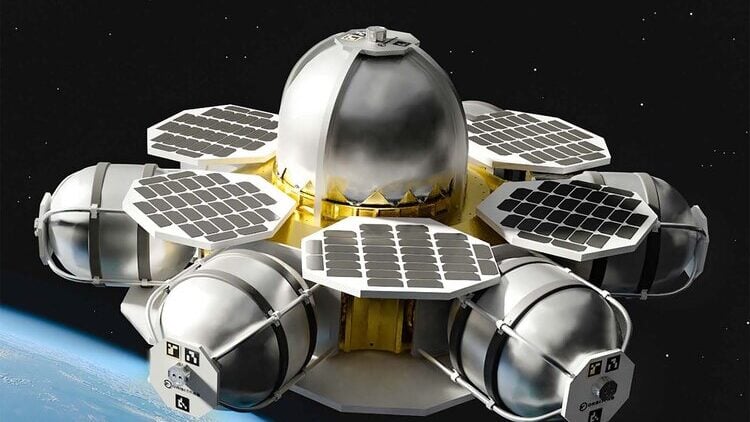

Commercial firm Orbit Fab in 2022 won a small Space Force contract to support its planned satellite refueling tanker to geosynchronous Earth orbit. (Graphic: Orbit Fab)

WASHINGTON — The White House’s draft bill to assign regulatory authority for new types of space activities — including missions such as on-orbit refueling that the Space Force is eyeing to underpin its push for space mobility — has set some industry nerves on edge and is being met with polite, and in some cases not so polite, skepticism on Capitol Hill.

“I don’t think any single company or industry group applauded the White House draft. So, you can tell a lot from that,” said one industry representative who works with a number of different companies and with Congress. “And really unfortunately, the White House proposal is sort of out of step with both where the House is, and where the Senate has been going.”

Currently, the Commerce Department (DoC), via the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, regulates commercial remote sensing systems; the Transportation Department (DoT), via the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), regulates commercial launch and reentry; and the semi-independent Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulates use of the electromagnetic spectrum, including by satellites.

But a plethora of companies are working to develop on-orbit capabilities and missions that fall outside of or across those individual lanes — many of which the Space Force and US Space Command see as supporting future “dynamic space operations.”

Filling the regulatory gaps is important because the Article VI of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty binds the US government to ensure “authorization and continuing supervision” of all non-government space activities.

The Biden administration’s legislative proposal in essence would split control for “novel” activities between the Departments of Commerce and Transportation.

But the draft, spearheaded by the National Space Council chaired by Vice President Kamala Harris, came as a bit of a shock to industry, as well as staffers on both sides of Capitol Hill who have been working on their own bills that divvy the power up differently. For one thing, the White House release came just an hour before the the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology was due to mark up draft legislation — to the frustration of many involved.

“That was a foul,” declared one lobbyist keeping an eye on commercial space policy-making.

The bill before the committee, cosponsored by Chair Rep. Frank Lucas, R.-Okla., and Rep. Brian Babin, R.-Texas, chair of the subcommittee on space and aeronautics, would set DoC up as the authoritative body, in what many in industry applaud as a more streamlined arrangement.

While admitting the timing wasn’t great, several government sources stressed that the National Space Council has been consulting with stakeholders over the 18 months since Harris announced the regulatory reform effort aimed at filling regulatory gaps, supporting US space innovation and, at the same time, ensuring the sustainability of the space environment for the future. There also have been several briefings specifically on the draft bill since it dropped Nov. 15.

Indeed, several industry representatives — including some otherwise critical as well as a few supporting the draft bill — praised the outreach efforts.

“I was encouraged by the willingness of the USG reps to continue to engage with industry as part of this initiative — not simply try to jam through the legislation,” one supportive industry rep said.

While in general US commercial space firms have been pushing for more certainty about how to get new types of space missions approved, the devil has been in the details — as the industrial base is far from monolithic, and companies often have competing priorities.

For example, there are many startups with roots in Silicon Valley whose founders have what one expert called a “space cowboy” ethos, seeing any regulations as obstacles to be hurdled rather than necessary guardrails. So, criticism from this faction was to be expected.

On the other hand, there also are a number of new companies with skin in the space sustainability game — working on missions such as removing dangerous space debris and repairing satellites on orbit — that have been much more welcoming of the administration proposal.

Nonetheless, there seems to be a coalescence of concern around two key pieces of the proposed White House legislation.

Harris’s office did not respond to a request for comment Wednesday for this report.

In-Space Transportation

The first is the draft’s proposed expansion of DoT’s role to cover in-space transportation missions, such as shuttling fuel to future on-orbit fuel depots or delivering cargo though space. There are worries both among companies and in Congress that the move will add to, not reduce, regulatory burdens — or at a minimum make the process more complicated by expanding the number of agencies involved.

“The proposal dramatically expands regulatory authority for both DOC and DOT with the potential for duplicative and conflicting requirements instead of focusing the agencies’ respective activities on criteria that reflect their specific areas of technical expertise,” the Commercial Spaceflight Federation argued in a Nov. 27 letter to lawmakers obtained by Breaking Defense.

According to participants, administration officials argued in industry briefings last week that the DoT’s FAA already has expertise in ensuring the safety of transportation to and from space, so it makes sense to give that department similar authorities in space as well.

But the debate about whether DoC or DoT should have primary responsibility for space traffic has been raging, especially in Congress, since the Obama administration. The fault lines are complex, driven partly by partisan politics, partly by jurisdictional jealousies between the agencies and their respective congressional overseers, and partly by differing attitudes within government and industry about the need for regulation.

Further, DoT, which focuses on safety, generally is seen as likely to be less flexible; whereas DoC, with its dual-hat as both a regulator and an advocate for US industry on the global market, is seen as more laissez-faire. The Obama administration wanted DoT as the regulatory hub for novel activities; the Trump administration flipped to backing Commerce.

The Biden proposal for a split thus dashed the hopes of many in industry who had been hoping “there was going to be a truly one-stop-shop at the Department of Commerce,” said another industry official. “I think that was probably the one big area of surprise.”

‘Black Box’ Fears

The other big bug-a-boo for industry is language in the White House draft bill that would allow government authorities, including the Defense Department, to put conditions on licenses to ensure “national security,” “national interest” and/or space “sustainability.” A number of sources complained that these terms are undefined, and thus give individual decision-makers virtually unlimited power to reject applications. (The House proposal, meanwhile, has no such language.)

“They are left up to their own discretion on determining what is meant by ‘national interest,’ so that’s a huge expansion of the existing process,” said one congressional critic.

Another industry official said there is a widespread fear companies could end up stuck “in a 12 to 24 month ‘black box,’ with no answers on why your system has not been approved.”

But government sources insist that this is by no means the case.

For one, the administration’s effort doesn’t include just the draft bill, but also an interagency implementation plan that a handful of government sources told Breaking Defense would drill down into the nitty gritty of how future rules would work. That plan, expected to be signed out before the end of the year, will include measures such as time limits for officials to make approval decisions to ensure a speedy process for applicants.

“This bill provides DoT and DoC with the authority to regulate commercial space activities, but doesn’t dictate the content of those regulations,” Richard DalBello, the head DoC’s Office of Space Commerce told Breaking Defense. “The details of any regulations would be worked through a normal notice and comment process. But it’s critical to provide these authorities to the [US government] now so that as industry engages in activities it’s never done before, the USG is in a position to say ‘yes’ to those activities rather than having to say ‘no’ simply because we don’t have the authority to approve them.”

The supportive industry representative agreed, saying, “I’m in favor of legislation that grants authorities and reduces uncertainty for industry and reduces interagency churn ‘behind the scenes.’ That’s the main thrust behind the administration’s proposal. Without authorizations there can be no accountability and limited leadership”.

But some company officials remain unconvinced.

“Telling me: ‘I’m creating a monster, but putting it in your closet,’ still means I have a monster in my closet. And I’d really rather not have a monster in my closet,” the industry representative said.

Congressional Roadblocks

The Republican-led House committee approved the Babin-Lucas bill today, although sources pointed out there is room for changes to be made in the language as it wends it way through the House.

The Democrat-led Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation isn’t as far along on its own bill, and thus several sources said it is likely to try to incorporate some of the White House draft’s provisions — in particular on sustainability. However, they noted that the Senate draft, like that of the House, has been focused on consolidating rule-making power with DoC.

Another issue, the congressional staffer said, is the potential costs of the administration’s draft. While no specific amount is requested, it is clear that the proposed reforms would require more people and resources for both DoC and DoT.

“They basically want a blank check,” the staffer said, making it clear that neither the congressional authorizers nor the appropriators are likely to concede to that.

Given the increasing dysfunction on Capitol Hill as next year’s presidential election looms closer, it is hard to predict what the upshot might be for any regulatory reform plan. But if one were a betting person, putting a mark on ‘yet more fruitless debate’ might be a solid choice.