The US Army just did something bold: It announced a cut of 6,500 active-duty aviation billets over the next two years, about one-fifth of its entire aviation branch. This isn’t trimming fat around the edges. It’s a deliberate move away from manned helicopters and toward unmanned systems, with talent panels now deciding which pilots and crew will remain in cockpits, and which will transition into new roles.

The easy reaction is to mourn the change. After all, generations of aviators have carried the Army on their shoulders in Iraq and Afghanistan. But the harder, truer assessment is this: The Army is adapting to the new reality. Inexpensive unmanned systems and air defenses in Ukraine and Colombia have swatted multi-million dollar helicopters out of the sky. To keep buying and manning yesterday’s aviation fleet is to prepare for the wrong war. By cutting 6,500 billets, the Army has forced itself to invest in the future and forced the rest of the Joint Force to confront its own reluctance to do the same.

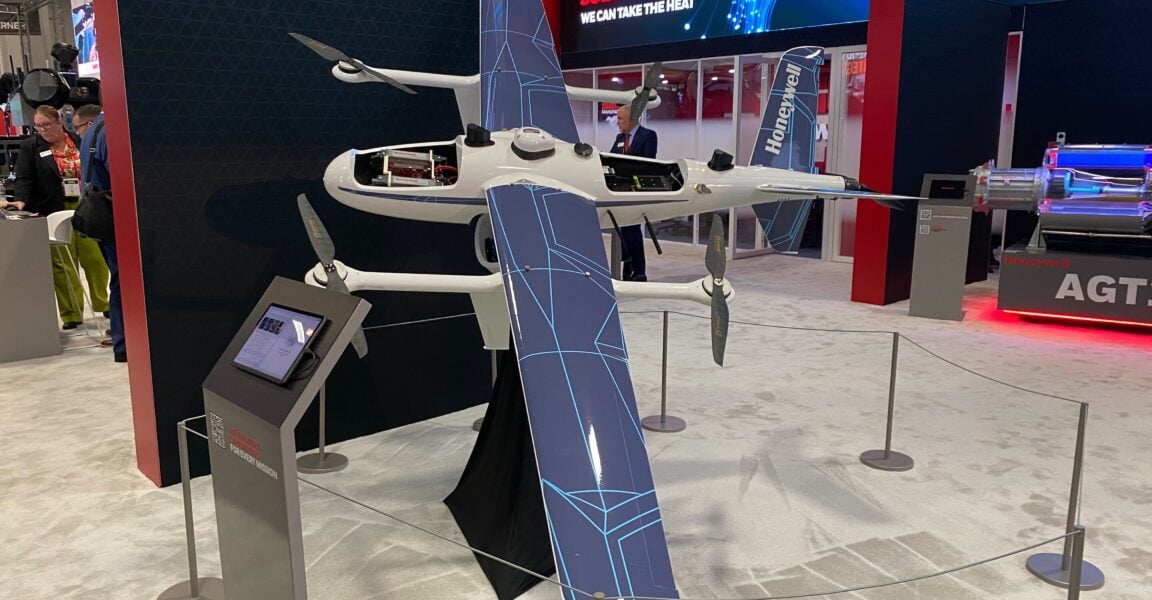

By moving quickly, the Army is signaling that they know that war has changed. Drones, autonomy, loitering munitions, and swarms will define the future battlefield, and the Army is getting ready to dominate it.

This is a tectonic shift. Army Secretary Daniel Driscoll is proving that he is both bold in thought and action, and should gain credit internally with Secretary Pete Hegseth for actually following his directions to the service. But the Army’s decision should also serve as a challenge to the other military branches to let go of the past and embrace the future.

There are several reasons the Army is right to make a large shift towards unmanned systems.

Start with survivability: Ukraine has shown that rotary-wing aircraft are fat targets for modern air defenses and more importantly, drones can kill helicopters cheaply. Then add in scale, realizing that for every Apache, the Army can field dozens of small or medium unmanned aircraft.

Cost and human capital is another factor: Helicopter pilots take years and millions of dollars to train. As Ukraine and others are showing, drone pilots can be grown virtually overnight, at a time when the sustainment bill for manned aviation is crushing.

If The Army Can, Why Not Everyone Else?

These are not problems unique to the Army. In fact, these same challenges are spread across the other three branches to operate manned aviation.

Look at the Air Force. It is sitting on a pilot shortage of roughly 2,000 aviators that it cannot close, even as it clings to legacy aircraft and insists on keeping manned fighters at the center of its force design. At the same time, the Air Force is trying to stand up Collaborative Combat Aircraft, an unmanned loyal wingman that is not intended to displace manned aviation.

Instead of admitting it cannot generate enough pilots, the Air Force is treating the shortage like a passing flu. The Army’s decision to cut 6,500 billets shows the opposite mindset: Own the problem, adapt the force, and move on. If the Air Force redirected its resources into unmanned aviation, it could close capability gaps far faster than it can ever fix its pilot shortfall.

The Marine Corps loves to present itself as lean and agile. But in truth, its budget is dominated by aviation. Depending on the year, 25 to 30 percent of Marine Corps readiness funding goes towards keeping aircraft flying. The CH-53K helicopter costs over $100 million per unit. The MV-22 Osprey, which has suffered repeated safety issues, is projected by GAO to cost between $7.5 to $9 million per year each for sustainment ($1.5 billion per year for 200 of them). For a service that prides itself on infantry-first warfighting, the Marines have allowed aviation to become their heaviest millstone.

If the Army can cut one-fifth of its aviation branch, surely the Marines can take a scalpel to a budget where aviation already outweighs infantry modernization. Imagine redirecting $10B of the CH-53K into unmanned drones, cheap reconnaissance systems, and loitering strike platforms that could actually survive in the next war.

The Navy has it worst of all. Its identity is tied to the carrier air wing, with squadrons of manned fighters projected from multi-billion-dollar floating airfields. Yet as I have argued before, naval aviation in its current form is a dead man walking. Chinese hypersonic missiles and long-range precision strike have turned aircraft carriers into sitting ducks. Betting the fleet’s future on short-legged manned fighters is folly.

And still, the Navy has not made the kind of trade the Army just made. Unmanned carrier aviation exists — look at the MQ-25 Stingray tanker or prototypes of carrier-launched drones — but progress is glacial. Budgets for unmanned sea vessels are crumbs compared to the billions poured into the F-35C. The Army’s decision should embarrass Navy leadership: If the ground force can cut 6,500 aviation billets, surely the Navy can cut squadrons of aviators and redirect those funds to unmanned ships and its sailing force.

Risks Worth Managing

None of this is easy. The Army risks losing generations of flight expertise. Soldiers who joined to fly may feel betrayed. And drones are not a magic bullet, vulnerable as they are to jamming, cyberattack, and attrition.

But the Army is not eliminating manned aviation entirely. Instead, it is beginning to strip away the illusion that manned platforms will remain the backbone of military aviation in perpetuity.

The Army has thrown down the gauntlet. It has shown that painful cuts are possible, that legacy communities can be trimmed, and that human capital can be reassigned. The question now is whether the other services will follow.

The Army’s decision to cut 6,500 aviation billets, over 20 percent of its branch, is one of the most significant adaptations any service has made since Ukraine exposed the vulnerability of legacy airpower. Driscoll and Chief of Staff Gen. Randy George deserve praise for courage. Now it is up to the other service secretaries to prove they too can face reality.

Ret. Maj. Gen. John G. Ferrari is a senior nonresident fellow at AEI. He previously served as a director of program analysis and evaluation for the service.