WASHINGTON: Are we giving Beijing mixed messages? On the one hand, the US Navy is getting ready — maybe — to challenge Chinese claims around their artificial islets in the South China Sea. On the other hand, the Navy’s also preparing to welcome three Chinese warships at Naval Station Mayport in Florida two weeks from now, reportedly the first such port visit on the East Coast. Chinese officers will go into Jacksonville to visit City Hall and maybe even meet the mayor.

The Navy considers all this normal activity, part of the complex balancing act of being a global superpower. Just this week, dozens of our officers visited the Chinese carrier Liaoning, as part of a week-long trip that, itself, was in reciprocity for an earlier Chinese delegation’s tour of the US. Whatever disagreements we may have, it’s vital to keep military-to-military relations (“mil to mil”) close and vibrant between us and a rising power, admiral after admiral has said.

Conservative Republicans aren’t so sure. We’re being a lot more open and welcoming with the Chinese, they say, than the Chinese are being with us — at a time when we should be pressing them on their bad behavior.

“Military to military exchanges with China, like the one planned at Naval Station Mayport, hold promise for broader understanding between our nations,” said the Jacksonville congressman — and defense appropriator — Rep. Ander Crenshaw in a statement to Breaking Defense. “Over the long run, however, a display of goodwill must indicate transparency of mission around the globe and, in particular, a de-escalation of unwelcome movements in the South China Sea.”

The chairman of the House seapower subcommittee, frequent Obama critic Randy Forbes, was much less restrained in his critique than Crenshaw.

“It just puzzles me that the Chinese continue to ratchet up their aggressive behavior [–] the artificial structures that they trying to put out in the South China Sea [and] the reckless intercept of some of our planes [–] and yet the way we tend to respond to that is by rolling out the red carpet to them and giving them the key to the city,” Forbes told me this afternoon.

That sends Beijing a signal, he argued, that they can keep adding insult to injury and we’ll never push back. The signal’s even stronger because — despite a lot of talk — we haven’t yet taken action in the South China Sea to challenge the 12 nautical mile radius Beijing claims around its artificial islets. Said Forbes, “I hear one day they’re going to do it, one day they’re going to study it, another day they’re going to do it again.”

“If it were up to me, I would have a direct correlation between Chinese behavior and the invites we give them on things that matter to them,” Forbes said. Given China’s bad behavior of late, he said, “I would not reward them by giving them mil to mil contacts.”

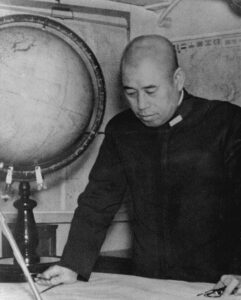

Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto

The Yamamoto Effect

Hold on, said the (conservative) Heritage Foundation’s Dean Cheng, a leading China scholar and no peacenik himself. “I think it’s a bad idea to view mil to mil as some kind of ‘reward,'” Cheng told me. “It’s a reward only if the other side is really interested in having it.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, the Chinese probably did want mil to mil with the US more than we wanted it with them, Cheng said. Nowadays? Not so much. In fact, when the Chinese agree to military-to-military contacts of late, he said, they often give the impression of a superior graciously granting a boon to supplicant subordinate — namely us.

The Chinese do intensely want a few mil-to-mil favors, such as the right to join — and spy on — the massive RIMPAC exercises, “where they get to see how we and our allies operate,” Cheng said. “But port visits?…. I don’t think that there is any reason to over-react to a port visit.” Trying to send diplomatic signals by granting or withholding such mundane mil-to-mil contacts, he said, is a lost cause.

“Insofar as both sides are interested in keeping military-to-military links open, we should be open to the idea,” Cheng said. They give each side a basic understanding of how the other operates, easing day-to-day interactions and potentially reducing dangerous miscalculations. Mil to mil is essentially a lubricant in the machine of geopolitics. That said, he warned, “what we should not be expecting is somehow, if we have mil to mil contacts, that it will transform US-China relations or even necessarily make a difference in in the event of a crisis.”

There Cheng and Forbes emphatically agree. “In almost every situation where there’s a crisis, it never works,” Forbes told me. “It doesn’t change their behavior. They don’t even take the telephone calls when you have an established telephone line.”

No amount of mil-to-mil will change Chinese nationalists’ minds on the South China Sea — they think it’s theirs — or on America’s rights to conduct reconnaissance flights off Chinese territory — they don’t think we have any. “Having just gotten back from China, they raised this point, saying, ‘no, you should not be here doing that,” Cheng said. “They have a fundamentally different view of freedom of navigation and freedom of the seas.”

Americans can have a naïve faith that if foreigners just got to know us, they would like us, they would want to be like us. That doesn’t always work. Even when it does, it doesn’t overcome a patriot’s pursuit of his own nation’s interest, even when they conflict with America’s. It doesn’t overcome a military officer’s obedience to orders.

In 1919-1921, a young Japanese student named Isoroku Yamamoto studied at Harvard. He thoroughly immersed himself in American life, mastered poker, toured the country during summer vacations, and later came back to the US as a naval attaché. When hawks in his own military pressed for war with the United States, now-Admiral Yamamoto argued the Americans were too strong. But when he got the order, he saluted and planned the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Despite being the most Americanized admiral in the Japanese fleet, Yamamoto was such a threat to the US that a special mission — Operation Vengeance — was dispatched to kill him. It succeeded when all the goodwill in the world had failed.

Shipbuilder Austal USA names Michelle Kruger as new president

Kruger had been serving as interim president since former chief Rusty Murdaugh resigned last spring.