AUSA: Lasers versus drones: It’s the cool versus awesome, ninjas versus pirates matchup of future warfare. The Army’s already experimented with a 10-kilowatt laser on a heavy truck, Boeing’s High Energy Laser – Mobile Demonstrator (HEL-MD), which could shoot down mortar rounds in flight. Now, while Lockheed scales up the truck-mounted laser to a whopping 60 kW, Boeing has scaled its laser down to 2 kW: still powerful enough to shoot down small drones, compact enough to fit in the Army’s eight-wheel-drive Stryker armored vehicle. (This Stryker also mounts radio jammers to scramble drones’ control links).

Strykers are built by General Dynamics, which worked closely with Boeing to fit the laser and jammers aboard this prototype. (We interviewed reps from both companies). In today’s force, Strykers equip the Army’s medium-weight brigades, a highly mobile compromise between light infantry and heavy armor. Compared to the truck-mounted HEL-MD, Strykers are much better protected and more mobile off-road — though they’re still not tanks — which allows them to operate on or just behind the front line.

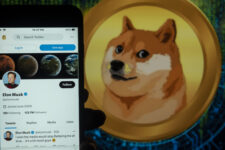

Kill count: A Boeing rep shows us how many drones the Stryker-mounted 2-kilowatt laser has shot down in testing.

In a way, the Army’s rebuilding the Short-Range Air Defense (SHORAD) capability it had during the Cold War. In the 1990s and 2000s, as the threat of Soviet fighter-bombers and attack helicopters gave way to roadside bombs and guerrilla fighters, the Army disbanded most of its anti-aircraft units and decided to depend on the Air Force to control the skies. But the rise of high-tech threats like Russia and China puts American air supremacy in doubt, and the Russians in particular have pioneered the use of small, low-flying drones to spot targets for artillery.

With cheap quadcopters now available online, there’s increasing anxiety that even low-end adversaries like terrorists may buy them for spying or strap on explosives to make “flying IEDs.” That’s why the Army is intensely interested in projects like this to put lasers on the front line.

Cutting losses? Assad, Syria, and Russia’s strategic flexibility

Russia’s failure to intervene as Bashar al-Assad’s regime fell may signal less about the Kremlin’s weakness than its cold strategic calculus.