Austal’s proposal for an LCS frigate with Vertical Launch System (VLS) tubes, one of which is shown firing.

UPDATED with Clark comment on shipyards WASHINGTON: The Navy needs to delay a year before awarding the roughly $9 billion contract for the upgraded frigate version of the Littoral Combat Ship, because it needs more time to thrash out cost estimates and detailed designs, says congressional watchdog GAO.

The Government Accountability Office has said this before, but a crucial piece of context has changed in a way that makes their case stronger — even though GAO doesn’t mention it in their new report. Specifically, one contractor’s frigate proposal opens the possibility of a much better-armed ship than the Navy had anticipated, and that’s worth slowing down to study.

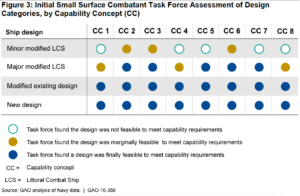

GAO’s comparison of the Navy’s eight concepts for upgraded LCS capabilities (CC1-CC8) and the four types of ships to install them on.

The last time GAO advised delay, it was not too hard to argue that the extra time wasn’t really necessary, because the frigate design wasn’t going to be that different from the current Littoral Combat Ship. In particular, that “minor modified LCS” would have new medium-weight anti-ship missile launchers mounted on deck, a Navy task force advised, but it would be too hard to build a heavy-duty, multi-purpose Vertical Launch system into the hull below deck.

Of the two competing contractors, aerospace giant Lockheed Martin toed the Navy line and didn’t add VLS, although they emphasize they could if asked. Upstart Austal, however, rolled out a frigate proposal with 16 VLS tubes. (For comparison, a much larger Aegis destroyer has 96 VLS). That would not only increase firepower but dramatically expand the range of missions the frigate could perform: VLS doesn’t just accommodate larger missiles, it can launch a wide range of different types at different targets, from enemy ships to incoming aircraft and missiles to Syrian airbases ashore.

Lockheed has proposed larger variants of the LCS, including ones with VLS, for foreign markets.

Is Austal’s proposal realistic? We need to know the trade-offs, said Bryan Clark, a former top aide to the Chief Of Naval Operations, who’d prefer a new, heavier frigate designed from the start to handle VLS. If you have to fit everything in the small hull of an LCS, Clark told me, adding VLS could require taking out too many other systems. Particularly at risk is kit for anti-submarine warfare, an increasingly important mission as the Chinese and Russian sub fleets grow in size and sophistication. Austal says their VLS-equipped frigate can still hunt subs just fine, but they do acknowledge it can carry fewer helicopters and drones than the original LCS, which could impact ASW and many other missions.

Bryan Clark

So adding VLS worth the cost, both in money and in other capabilities you have to leave off the ship to make room? That answer requires a complex mix of engineering and tactical analysis — analysis the Navy doesn’t plan to do before it commits to a design.

The Navy originally planned to award the frigate contract in 2019, after detailed design work was done on both competitors. Under pressure from the Pentagon to get a better-armed ship in the fleet as fast as possible, however, the service moved that date up a year to 2018 — before detailed design. Likewise, there won’t be a final cost estimate in time for a 2018 award. (There will be an Independent Cost Estimate from the Cost Assessment & Program Evaluation office, CAPE). The Pentagon also won’t have completed important tests of LCS systems that will carry over to the frigate: Survivability analysis won’t be complete until 2018; Initial Operational Test & Evaluation of the anti-ship systems won’t be complete until 2018, and IOT&E of anti-submarine systems not until 2019.

USS Jackson (LCS 6) rides out a nearby explosion during its full-ship shock trials.

Admittedly, lots of defense programs commit to contracts before they know exactly what they’re buying, in order to speed things along, but it’s always a risky decision. LCS is a poster child for why not to take shortcuts, because skipping the normal analytical process was the program’s original sin, which led to expensive design changes halfway through building the first ships, to undersized crews that couldn’t keep up with maintenance, and to limited lethality and survivability. Leading naval analyst Ron O’Rourke has written that the study leading to the frigate took similarly problematic shortcuts.

In this case, the Navy argues it doesn’t need detailed designs to go ahead, because the frigate will be “over 60 percent common” with the current LCS. Of course, that means the frigate will be up to 40 percent different, and that’s without adding a Vertical Launch System.

So why the hurry? One argument is the shipyards need the frigate contracts to keep working at a steady pace, without a hiatus in production that would force layoffs of skilled workers who might never return. But GAO calculates current LCS contracts will keep both competitors busy into 2021.

[UPDATE] Bryan Clark told me GAO’s oversimplifying the timeline. Yes, some work will continue on the already-contracted ships through 2021, but the kind of work and which workers are employed to do it will change in problematic ways. “The shipwrights and fabricators who build hulls and frame the modules do most of the work for about the first quarter of the construction time, then the electricians, welders, and pipefitters who assemble the modules take over, and finally during the last quarter of the construction time, the work is mostly being done by vendors who outfit the ship with mission and combat systems,” Clark said. “If the Navy doesn’t build any LCS after the ones bought in FY17, then by 2019 the shipwrights and fabricators will probably run out of work and need to be laid off. Then the electricians, welders, and pipefitters will finish most of their work by 2020 and start being laid off.”

The other argument against a delay is that the fleet needs the upgraded ship ASAP. But if the choice is between getting 12 modestly upgunned frigates starting in 2018 and 12 VLS-capable frigates starting in 2019, a year’s wait doesn’t look too long.

Coast Guard’s Fagan, first female service chief, removed by Trump administration

Rep. Joe Courtney, D-Conn., today called Fagan’s firing an “abuse of power” and praised her record as the service’s chief.