France’s first FREMM frigates, the Aquitaine and Normandy, built by Italy’s Fincantieri.

[UPDATED with Sec. Stackley comments] WASHINGTON: The Navy is seriously considering derivatives of foreign designs and the Coast Guard’s National Security Cutter for its new frigate, after three years pursuing an upgraded version of its current Littoral Combat Ship. The shift has shaken up the industry, panicking some players, while others quietly reposition:

- Wisconsin’s Marinette Marine, which currently builds the 3,500-ton Freedom variant of the LCS, may instead offer an Americanized version of the FREMM, a 6,000 to 6,700-ton frigate built for the French and Italian navies by Marinette’s parent company, Fincantieri. If so, Marinette would probably part ways with its current prime contractor, Lockheed Martin, and contract directly with the Navy.

- Maine’s Bath Iron Works (owned by General Dynamics) will probably revive a previous partnership with Spanish shipbuilder Navantia, whose 5,900-ton F-100 family has the same Aegis radar and air defense system as American destroyers. That makes it the most sophisticated but also probably the most expensive contender, unless they deliberately downsize the radar to cut cost.

- Mississippi’s Ingalls — whose parent company, HII, also owns Virginia’s massive Newport News — is dusting off proposals to militarize its Legend-class Coast Guard National Security Cutter as a 4,675-ton Patrol Frigate, the smallest and likely the cheapest competitor. Offering the only alternative to LCS that’s invented in America, Ingalls has a definite edge.

- Alabama’s Austal, which builds the 3,100-ton Independence variant of LCS, specializes in building lightweight, high-speed aluminum ships, leaving them with little option but to offer an upgraded Independence. Austal says that hull is still large enough to accommodate high-end equipment like Vertical Launch Systems.

A Spanish F100-class frigate, Almirante Juan de Borbon, built by Navantia.

Other options got honorable mention from our sources. BAE System’s Type 26 Frigate for the Royal Navy looks promising, but isn’t built yet so it has no track record. Denmark’s Iver Huitfeldt frigates rely on plug-and-play StanFlex equipment modules, a concept that’s already proved problematic on LCS (which they inspired).

In general, many foreign frigates are over-built for the US Navy’s needs. Global navies often use frigates as the mainstay of their battle line, a role the US reserves for much larger destroyers, so they pack their frigates with expensive high-end systems, especially for wide-area air defense. The US Navy wants to keep the frigate affordable, with more air defense than LCS has today but less than its scores of Aegis destroyers already on hand.

“They are looking for something in the $700 million to $1 billion range,” said Bryan Clark, a retired but well-connected Navy strategist the Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments, which itself recommended a larger frigate in a recent congressionally-chartered study. That’s as compared to $550 million for the latest Littoral Combat Ships, whose price has come down dramatically since early overruns, and about $1.8 billion for an 8,200-9,700 ton Aegis destroyer. “If it could be half the price of a destroyer, that’s probably the ideal.”

[UPDATED] “It’s going to be a best-value type competition, so cost and capability will be factors,” acting Navy Secretary Sean Stackley told reporters this evening after the US Naval Institute’s annual meeting. “I expect there to be a range of designs,” both LCS derivatives and others.

Sean Stackley

“If you’re an existing builder (i.e. Austal and Marinette), you are in a competitive position because you have a hot production line (and) you’ve got mature costs,” he said. “Now their challenge is integrating new capabilities.”

At the same time, “definitely, the competition will be open to foreign designs,” Stackley said. “There are going to be some caveats”: All contenders must meet US requirements, especially for survivability; they must give the Navy technical data rights so it can “sustain and modernize” the ships; and they must be built in US shipyards.

Is there any preference for domestic vs. foreign, LCS derivatives vs. different designs? Stackley simply repeated the Navy’s promise that the competition would be “full and open.” [UPDATE ENDS]

No final decision has been made, but five knowledgeable sources from different backgrounds– Capitol Hill, the executive branch, industry, and academia — and with no evident connections to each other, all independently (and all anonymously except for Clark) told me that the Navy is seriously considering alternatives to an upgraded LCS. The service isn’t just doing due diligence or paying lip service with every intention of choosing the LCS frigate in the end. In 2020, when the Navy intends to award the frigate contract, it could well end up buying an up-gunned Coast Guard cutter or a foreign design — assuming Congress and a protectionist president permit.

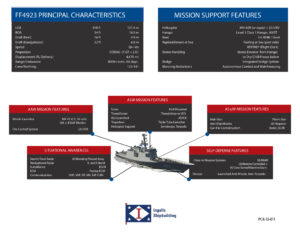

Huntington Ingalls concept for their Patrol Frigate, a militarized version of their Coast Guard National Security Cutter.

“We’re not going to buy foreign…. even to buy their design (and build it here),” said Norman Polmar, a noted naval historian and LCS critic (but not one of our five sources on the Navy’s shift). “US shipyards have too much influence with Congress….The couple of times it’s been raised, (Congress) has just jumped and said no.”

While Senate Armed Services chairman John McCain has publicly pushed the Navy to consider alternatives to LCS, some legislators are already antsy. Last week, the ranking Democrat on the House seapower subcommittee, Connecticut’s Joe Courtney, asked Navy witnesses about reports by Defense News and the US Naval Institute that the service was looking at foreign designs and the National Security Cutter. The Navy’s own analytic team concluded back in 2014 that these vessels would require expensive upgrades to meet the same survivability standards as the current LCS, Courtney noted pointedly: “What has changed and why’s the Navy again questioning the exhaustive process of the Small Surface Combatant Task Force?”

The two Littoral Combat Ship variants, LCS-1 Freedom (far) and LCS-2 Independence (near).

The Reason Why

The answer to Rep. Courtney’s question — to boil down Rear Admiral Ronald Boxall’s carefully circuitous reply — is that the task force process, compressed as it was into seven months under intense pressure from the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), wasn’t actually all that “exhaustive.” In fact, both the Government Accountability Office and one of Washington’s leading naval experts, the Congressional Research Service’s Ronald O’Rourke, has said the task force short-circuited the normal analysis, much as the original launch of the LCS program had done.

What’s more, the world has changed. The 2014 decision was made at a time when OSD was increasingly focused on high-intensity warfare against great powers — Russia and China — but the Navy still gave equal priority to global patrolling and presence in low-threat zones, hence the conflict over LCS. Since then, especially with Russian offensives in Ukraine and Syria, and especially under new Chief of Naval Operations John Richardson, the Navy has refocused on high-end threats.

Adversaries with jet aircraft and anti-ship missiles put a premium on air and missile defense, for which the current LCS largely depends on escorting Aegis destroyers. Adversaries with well-armed surface warships put a premium on long-range anti-ship weapons, which the current LCS lacks. Adversaries with attack submarines also put a premium on anti-submarine warfare, which is a primary mission of the current LCS, although the ASW “mission module” is still in testing. The Navy, Austal, and the Marinette-Lockheed team have all worked hard to cram more of these capabilities into the current LCS hull designs, but there are limits.

Austal’s proposal for an LCS frigate with Vertical Launch System (VLS) tubes.

The most obvious issue is sheer size: Littoral Combat Ships displace 3,100 to 3,500 tons, depending on the variant, while many foreign frigates exceed 6,000 tons, nearly twice as large. Compounding the problem is that both LCS variants are optimized for speed, not carrying capacity: Marinette’s Freedom skims across the water like a speedboat, Austal’s Independence is an all-aluminum trimaran, and both devote much of their hull space to outsized (and unreliable) engines. That made some sense for the original operating concept, which called on LCS to chase and evade high-speed fast attack boats in coastal waters, for example off Iran, at a blistering 40-plus knots. In a major war, by contrast, the future frigate would escort aircraft carriers — which max out at 30-plus knots — and support vessels — about 20 knots — while relying on long-range missiles, not its own speed, to catch distant targets. The upgraded LCS designs do sacrifice some speed to add weaponry, but if they can’t get rid of their streamlined hull shapes or their disproportionate power plants.

Now, small ships can pack quite a punch — Norman Polmar wryly suggested the US just buy Russian designs, like the corvettes and frigate that fired cruise missiles over 900 miles from the Caspian Sea into Syria. Both Austal and Marinette-Lockheed have drafted designs for upgraded LCS that include heavy-duty equipment such as Vertical Launch Systems, the Navy’s multi-purpose missile tube used for both offensive and defensive weapons. But small ships with big weapons often lack endurance, because they skimp on ammunition reloads, fuel reserves, and crew size — all classic problems with Russian ships.

By contrast, Huntington-Ingalls’ National Security Cutter is designed for long Coast Guard cruises in bad weather, including Arctic patrols. The NSC’s range is 12,000 nautical miles, compared to the LCS’s 3,500 — or for that matter the foreign frigates’ 5,000 to 6,000 miles. Indeed, the militarized NSC design, the Patrol Frigate, would trade off some of that fuel supply, going down to a still-remarkable 8,000 nm, for additional weapons such as a 16-tube VLS.

By contrast, Huntington-Ingalls’ National Security Cutter is designed for long Coast Guard cruises in bad weather, including Arctic patrols. The NSC’s range is 12,000 nautical miles, compared to the LCS’s 3,500 — or for that matter the foreign frigates’ 5,000 to 6,000 miles. Indeed, the militarized NSC design, the Patrol Frigate, would trade off some of that fuel supply, going down to a still-remarkable 8,000 nm, for additional weapons such as a 16-tube VLS.

The much larger foreign frigates can carry much more firepower: 24 to 48 VLS cells on the Navantia F-100 family, depending on the model. The Fincantieri FREMM has just 16 cells, same as the Patrol Frigate. They also have sophisticated military-grade radars, sonars, and other sensors that the National Security Cutter currently lacks, although Congress might require reequipping the FREMM or Navantia with made-in-America kit.

The harder question is whether the European ships are up to US Navy standards of survivability. It’s complex mix of the ability to avoid a hit — by shooting down an incoming missile, for example — and the ability to take a hit — thanks to a reinforced hull, say, or large damage-control teams. LCS’s own survivability has long been a matter of bitter debate, and the Navy’s decision to toughen up the first two ships halfway through their construction led to massive cost overruns. European warships, however, are often built to commercial standards that make LCS look like a dreadnaught — although that’s not necessarily true of these particular frigates.

Lockheed has proposed larger variants of the LCS, including ones with VLS, for foreign markets.

“The task force had said that the foreign designs don’t even meet LCS survivability requirements, so to bring them up to even just the minimal amount of survivability the LCS has, much less an increased survivability, the Navy would have to do major modifications, and that’d start to have major impacts to cost,” said one Hill staffer. “So I never thought the Navy was seriously looking at that, (and) I still think it is not very serious.”

Bryan Clark disagrees. Unlike the Hill staffer, Clark is one of our five principal sources saying the Navy is serious, and the only one willing to speak on the record without conditions. “I saw them going this direction a few weeks ago…They do realize the need for a more robust air defense capability and also (offensive) distributed lethality,” he said. “Those drive you to a larger ship than a LCS… A modified LCS might be in the mix, but a significantly modified LCS might be just as expensive as a FREMM or a NCS or a Navantia frigate.”

The new focus is going beyond just talk, Clark made clear: “They’ve got a program manager for the frigate program who’s separate from the LCS program manager, (and he) has been operating more independently of the LCS.” (That said, both entities remain under the same Program Executive Office).

The Navy’s even given out public signals. It told US Naval Institute News it would “explore other existing hull forms.” A document obtained by Defense News mentioned “designs beyond the two current LCS variants.” And in his prepared statement to the seapower subcommittee, Rear Adm. Boxall repeated the mention of “other hull forms,” telling Courtney in the hearing that the Navy wanted to “include anyone who could provide full and open competition to get us the best capability at the best price.” But they’ve not publicly said what our sources tell us, that both the National Security Cutter and foreign designs will probably be considered on equal footing with an upgraded LCS.

That’s understandably unnerving for the current incumbents, Austal and (to a lesser extent) Marinette, and for the congressional delegations from the Gulf Coast and the Great Lakes. “Now you’re talking about potentially putting two shipyards out of business,” said the Hill staffer. Before the Navy changes course, the staffer said, “we need to make sure that risk is understood.”

Sullivan: Defense industry ‘still underestimating’ global need for munitions

National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said that there are “no plans” for another Ukraine supplemental at this point.