An F-18C tests the JPALS assisted-landing system aboard the USS Theodore Roosevelt

AFA: Why on earth is Raytheon pitching an assisted-landing system developed for aircraft carriers to pilots that land on, well, land here at the Air Force Association conference? Why will Raytheon be at the Association of the US Army conference next month, pitching the same Navy-funded technology to a service that flies helicopters almost exclusively?

Because the defense contractor is convinced that the same Joint Precision Approach & Landing Systems (JPALS) that helps Navy and Marine pilots find a pitching carrier deck in all sorts of weather can also help Air Force jets and Army helicopters find airfields on land through darkness, dust storms, and enemy jamming.

F-35C

The F-35 Joint Program Office, at least, is receptive. JPALS software is currently being installed on all three models of the Joint Strike Fighter as they come off the production line. That said, only the Marine F-35Bs and Navy F-35Cs have JPALS turned on, while the Air Force F-35As don’t. That’s part of what Raytheon wants to change.

LT Brooks Cleveland flying the F/A-18 at the Hillsboro Airshow from Cory Lovell on Vimeo.

Cmdr. Brooks Cleveland, a Navy Reserve pilot who works on JPALS for Raytheon, has a personal stake in the system. As a landing officer aboard the USS Vinson, he had to guide seven aircraft to a landing through a dust storm that cut visibility to only an eighth of a mile (660 feet), giving pilots about a second between first glimpsing the carrier and touching down on it. On a separate occasion, Cleveland’s twin brother, also a naval aviator, had to ditch his F-18 fighter in the ocean because he was running out of fuel, couldn’t reach his carrier, and the first divert field he was sent to had to shut down for bad weather. (He’d tried to refuel in mid-air from a tanker aircraft, only for an accident to snap off the probe and send it into an engine intake, crippling his plane).

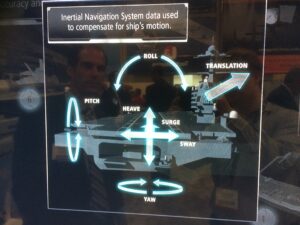

JPALS would have solved both problems, Cleveland told me at the Raytheon booth here. The carrier-specific part of the system tracks the gut-churning “pitch, roll, surge, sway, heave, yaw, and translation” of the carrier deck. But the precision navigation portion is relevant to any kind of landing at sea or ashore by any kind of aircraft, jet, propeller, or helicopter.

The different factors JPALS must track for a carrier landing. (Raytheon’s Brooks Cleveland is visible in the reflection, on left; the author on the right).

JPALS starts communicating with incoming aircraft at 200 nautical miles (230 statute miles) out. Since it uses modern datalinks rather than simply broadcasting in all directions, it’s much harder for enemies to detect – potentially saving the airfield from bombardment – and much harder for them to jam – potentially providing a navigation lifeline when other systems get shut down. The land-based version can be fit into a single Humvee-plus-trailer combo and it can even be parachuted in.

The precision part of JPALS comes from a set of differential GPS receivers – three installed at various points on a carrier or four around a terrestrial airfield – that cross-check each other to eliminate the usual margin of error in the GPS signal. Cleveland said they provide the incoming pilot with not just the location of the airstrip or carrier deck but a 20 centimeter (7.8 inch) box to touch down on. JPALS shows the pilot how to fly to that 20cm target even when a moonless night or heavy weather reduce visibility to zero.

An Army UH-60 Black Hawk tries to navigate through the dust cloud created by its own rotors.

What’s more, Raytheon is finishing development of a capability for JPALS to take over the flight controls and bring the aircraft in for an automated landing with no input from the pilot – or potentially with no pilot on board at all. That is why the Navy has contracted with Raytheon to put JPALS on its future MQ-25 carrier-based drone.

There are things JPALS can’t do, Cleveland acknowledged. A pilot conducting a carrier landing would do well to have both JPALS and the Navy-developed MAGIC CARPET installed, JPALS to pinpoint the carrier deck precisely and MAGIC CARPET to touch down on it smoothly. A helicopter pilot trying to land in a dust storm or other degraded visual environment (DVE) would do well to have both JPALS, to find the landing zone, and some kind of collision avoidance sensor, to warn of tree branches, power lines, and other obstacles that might not be in JPALS’ map database.

Despite these limits, Raytheon believes JPALS will be a crucial part of any military aircraft’s kit. It doesn’t solve every problem, but the problem it does solve – landing safely while blinded by the weather – is one that could save lives for every service.

Lockheed wins competition to build next-gen interceptor

The Missile Defense Agency recently accelerated plans to pick a winning vendor, a decision previously planned for next year.