A soldier from the Army’s offensive cyber brigade during an exercise at Fort Lewis, Washington.

What if the next war starts, not with a gunshot, but with a tweet? As tensions rise, US troops discover their families’ names, faces, and home addresses have been posted on social media as they prepare to deploy, along with exhortations to kill the fascists/imperialists/infidels (pick one). Trolls call them late at night with death threats, a mentally ill lone wolf runs over a soldier’s children, fake news claims the military is covering up more deaths, and official social media accounts are hacked to post falsehoods. The whole force is distracted and demoralized.

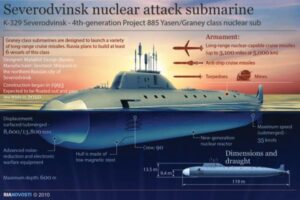

Russia’s most advanced attack submarine, the Severodvinsk class. (Navy graphic)

Meanwhile, defense contractors discover the networks they use to deliver supplies to the military have been penetrated. Vital spare parts go missing without ever leaving the warehouse because the serial number saying which crate they’re in has been scrambled in the database. As railways and seaports prepare to transport heavy equipment, they discover key railroad switches, loading cranes, and other equipment – civilian-owned but vital to the military operation – now malfunction unpredictably, forcing prolonged safety inspections.

US forces finally cut through this cyber thicket and begin to deploy abroad by air and sea – but now the shooting starts. A thousand miles from enemy territory, submarines sink transport ships with torpedoes, cruise missiles and covertly laid mines. A few hundred miles out, long-range anti-aircraft missiles blunt the US air offensive. While stealth fighters can penetrate the defenses, the lumbering fuel tankers that let them cover long distances cannot. Transport planes must unload the troops at airfields well outside the danger zone, while transport ships must unload at distant ports.

A US Army M1 tank about to be shipped out for the Trident Juncture wargames.

US forces face a long road march just to reach the ally they’re supposed to be defending. The whole way, they must fight through attacks by everything from surface-to-surface missiles to local malcontents stirred up by social media. By the time the Americans arrive, their ally’s territory is not only occupied but thoroughly defended by dug-in enemies.

Rather than risk reenacting the Battle of the Somme with smart bombs, US leaders decide to negotiate. Surely the independence of one little ally isn’t worth so many American lives? Surely countries can’t expect America to honor its treaties with them when they don’t pay their fair share for the common defense?

This war hasn’t happened yet, of course. Hopefully, it never will. But to paraphrase a former Army Chief of Staff, hope is not a strategy. This nightmare scenario is what the Army’s nascent Multi-Domain Battle initiative is intended to prevent.

No Safe Havens

“Our traditional view of the battlefield is pretty narrow,” Brig. Gen. Mark Odom told me in a recent interview. He’s the director of concept development for the Army Capabilities Integration Center (ARCIC), part of Training & Doctrine Command (TRADOC).

“Geographically, our notion of the battlefield has been limited to the rates of vehicle movement (and) range of conventional weapon systems,” Odom said. Temporally, “we principally focus on…armed combat,” which military doctrine clearly distinguishes from peacetime operations.

Brig. Gen. Mark Odom

But modern warfare radically expands the battlefield in both space and time, said Odom. The danger will start before the enemy’s first shot and reach far beyond the range of his guns. It will violate places we consider sanctuaries, such as the United States, and times we think of as peace.

Conflicts can start much earlier, but the American way of war is to assume we are at peace or not. There’s little planning fluidity to cope with disruptions that aren’t directly tied to fighting. As the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Joseph Dunford, said last year, “Our traditional approach where we are either at peace or at war is insufficient to deal with that dynamic (of) an adversarial competition with a military dimension short of armed conflict.”

Unconventional forces may strike in grey zone operations long before conventional troops officially go to war, if they ever do. The first blow may be struck by proxies like the Russian-backed Ukrainian rebels, deniable forces like the Little Green Men in Crimea or Chinese state-owned fishing vessels in the South China Sea, non-military government agencies like the Chinese Coast Guard, or “lone wolves” inspired to act by social media but with no connection to the enemy. It may come from cyber attacks, whose origin is notoriously hard to figure out, and which may involve months or years of careful preparation but then take effect in seconds.

Gen. Joseph Dunford

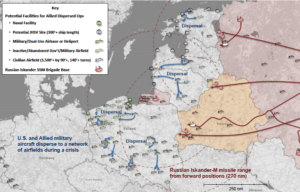

Meanwhile, distance shrinks. “Space, information, cyber are limitless, they’re not tied to geography,” Odom said. “That now all of a sudden means there’s no such thing as a safe haven. There’s no such thing as a unit’s that out of contact. You can be put in contact….anywhere in the world.” That reality breaks down the current crisp demarcations between war zones and the rest of the world, between one geographic theater command and another, which is part of why Chairman Dunford has called for a new joint staff to deal with “transregional” threats.

A cyber attacker anywhere on Earth can hit targets anywhere on Earth, as long as they’re both online – and sometimes even that’s not necessary: Consider how Stuxnet slipped into the closed-circuit Iranian nuclear program network over a thumb drive. Long-range smart weapons can hold US bases, aircraft, and ships at risk in what were previously considered safe transit zones. Long range, precision guidance, and sharing target data over networks also allow widely scattered forces to coordinate their attacks and converge on a single target.

Defense of the Baltic States and Poland against a notional Russian missile barrage. (CSBA graphic)

“The battlefield … it’s expanding, it’s converging, and it’s compressing,” all at once, Odom said. The battlefield’s expanded in terms of space and time, in terms of the number of actors both conventional and unconventional, and in terms of environments – to the traditional domains of air, land, and sea, add space and cyberspace. It’s converged and compressed because “now you can bring effects from virtually anywhere in the world to virtually any location in the world,” he said. The grunt on the ground used to worry mostly about the enemy grunts in front of him, plus the occasional artillery barrage and – before 1953 – perhaps an airstrike. Now he has to worry about long-range missiles coming from hundreds of miles away and cyber attacks coming from anywhere, capabilities tactical units can’t counter by themselves.

“The enemy has the ability to engage us virtually from the continental United States… into that tactical box (of traditional close-in combat),” Odom said. “They can engage us simultaneously and in depth throughout the entire battlefield.”

The Army’s new six-zone “battlefield framework” extends far beyond the warzone envisioned in the classic AirLand Battle doctrine.

Fighting Back

So how can the US compete? We have to start by realizing we’re always in competition, Odom said. In fact, the new concept envisions no such thing as “peacetime.” “The concept is saying, ‘look, you’re either in competition or in armed conflict,'” he said. “Victory is never final.”

US Army cybersecurity personnel

Constant competition requires constant vigilance. US forces must always be on their guard against cyber attack, disinformation, and terrorism, not only on deployment but also at home bases. They must realize the adversary may be watching at any time – online, over radio waves, using drones, or physically on the ground with binoculars – and stand ready to defeat that reconnaissance with everything from electronic jamming to hidden missile launchers. They must be swift to counter enemy propaganda with the American message to win hearts and minds both in the US and abroad.

US forces must also realize that both sides’ conventional forces are maneuvering for advantage, even in “peacetime,” moving into better positions from which to attack or defend. For our adversaries, Odom said, “the distinction… between peace and war is non-existent, and they’re really one snap exercise away from armed conflict.” For us, he said “this competition period (is) actually when we have the greatest freedom of maneuver in all domains.

Chinese weapons ranges (CSBA graphic)

That means US forces shouldn’t wait to deploy until the shooting starts, at which point they will have to fight their way through the enemy’s defenses. Instead, they should deploy to the danger zone in what passes for peacetime, getting dug in before the enemy’s missile launchers go live. “We want to be inside the anti-access area denial bubble, not fighting into it,” Odom said. This way, rather than let the enemy set up their no-go zone unchallenged and then try to attack it from the outside in, US forces will be on the ground inside it from the start to “deny the denial.” At worst, these advanced forces will be cut off and overwhelmed. At best, they’ll deter aggression altogether. In scenarios in between, they will act as a foot in the door for follow-on forces.

Those follow-on forces will need to move from home base to front line without stopping to regroup along the way. They’ll also need to do it while under attack or threat of attack the entire way.

“They’re going to have to maneuver, without secure flanks, without continuous communication, from the continental United States or another theater to where the armed conflict is,” Odom said, “and we want to be able to do that straight into combat, (because) our adversaries are not going to give us 120-150 days to build up forces.”

A Joint Tactical Air Controller (JTAC), trained to call in airstrikes.

Finally, US forces must be multi-domain from the start. That goes far beyond current concepts of jointness – Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marines all supporting one another – to a more seamless integration. Multi-domain forces must maneuver and attack simultaneously in air, sea, land, space, and cyberspace, exploiting whatever domain the enemy is weakest at that fleeting moment to try to roll them back in the others.

That might mean Army artillery sinking enemy ships so the Navy can safely land Marines. It might mean cyber units shutting down enemy radars so Air Force fighters can support a ground attack. The possible combinations are dizzying, and executing them in practice will require a new sophistication in training, planning, and networking. It’s the need to coordinate such fast-moving complexity that is driving the US military towards the use of artificial intelligence, with the holy grail being a kind of War Algorithm that helps calculate the path to victory.

In the future, “we don’t want single-domain formations” — just land, just air, just sea, and so on — Odom said. “We want all formations, regardless of whether they’re maneuver (or) logistics, (i.e. combat or support), to be multi-domain formations or have access to multi-domain capabilities.”

China’s new H-20 stealth bomber ‘not really’ a concern for Pentagon, says intel official

“The thing with the H-20 is when you actually look at the system design, it’s probably nowhere near as good as US LO [low observable] platforms, particularly more advanced ones that we have coming down,” said a DoD intelligence official.