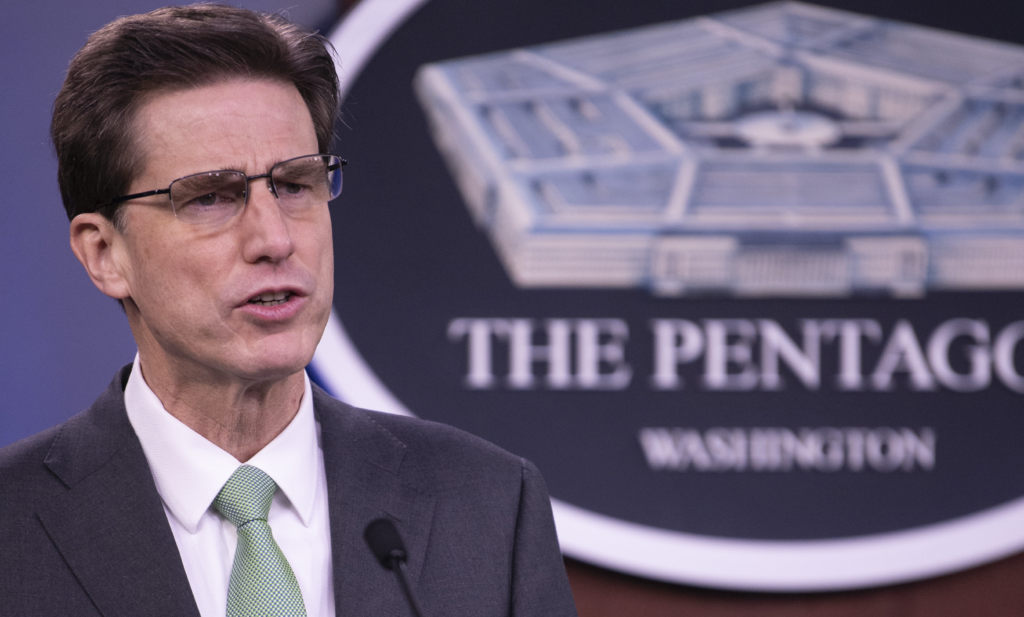

ALBUQUERQUE: Military information is too important to store in a single cloud. Although the $10 billion JEDI contract dominates public conversation about military cloud services, the Pentagon’s Chief Information Officer Dana Deasy says the department is creating its own repository of shareable code for managing the constellations of clouds within the Pentagon.

Deasy’s call took place on the Commercial Virtual Remote Environment (CVR), itself a platform Deasy said last Thursday is “supporting nearly one million active DoD users with voice, video, and chat capabilities today.”

CVR, which requires users to download a desktop client, is a cloud-based environment for communication, and its adoption by the military in part comes as a needed response to the COVID-19 pandemic. As demonstrated, CVR ably handled audio for at least fifteen call participants, with more on the line.

CVR remains capable of handling unclassified information, but to truly enable the Pentagon to work remotely and seamlessly through the environment, work still needs to be done. CVR functions at an Information Impact Level of 2, for low confidentiality information suitable for public release.

“Now, the trick in doing that is you don’t want to lose the goodness of how we’ve been able to allow people to work off-net, so to speak, from their home, from their own types of devices,” said Deasy. “But how do you now transition to an [Impact Level 5] world which locks down things in a lot more restrictive way, and obviously, for very good reasons?”

An Impact Level 5, as outlined by DoD guidelines, allows Controlled Unclassified Information (like For Official Use Only) and National Security Systems. The plan, said Deasy, is to figure out how to pivot CVR from only handling information with a low confidentiality level to a greater degree of confidentiality by the end of the year.

Maintaining the cloud behind CVR, and the clouds behind other applications, means constant work updating and securing the cloud, work that only becomes more important the more sensitive information is available on the cloud’s servers. One approach for managing this is to build libraries of useful code to plug-and-play into existing systems to patch familiar problems.

“Obviously, when you think about sources like GitHub, it’s all about what we call, you know, the DoD version of it in terms of highly-secured,” said Deasy. “We’re really focused on, how do you take things like APIs (Application Programming Interfaces), micro-services, which are kind of the building blocks of reuse, where we’re trying to get coders out of the world of thinking that every time they need to make a call to something — you know, a simple thing like someone’s developing a repository to track troop movements and show the dots on a map.”

A shared repository of useful code means that, as the Pentagon works to sustain and use several clouds, the answer to a new problem could already be waiting and shared for a programmer to slot into place. If a certain string of code fixed the problem in an Air Force cloud, say, it is likely that same could could, if shared through this library, let an Army programmer fix a similar problem in an Army cloud. In this way, the code library saves the Pentagon from, first, reinventing the wheel, and second, from having to send dedicated specialists to a problem, instead of just sharing the work they already did remotely.

A library of useful code only works if everyone who might need it regularly uses that library. Deasy emphasized the role in training DevSecOps personnel within the Pentagon to use the repositories, tag and label code, and then most importantly, make the code shareable within the Department.

New ways to communicate from ground to space and across domains

Software-defined radios that fuse comms, electronic warfare, and SIGINT allow for rapid fielding and improvement of the kill chain.