Russian nesting dolls (via Wikimedia Commons)

WASHINGTON: New revelations from Amazon and analysis from experts explain why the online giant filed a puzzling protest with the Pentagon earlier this week. Like a set of Russian nesting dolls, the protest fits inside Amazon’s larger strategy in its ongoing lawsuit over the JEDI cloud computing contract.

Officially, the so-called “agency protest” is an appeal to the Pentagon, asking it to clarify its criteria for a do-over of what was – as DoD itself admits — a flawed portion of the evaluation that awarded JEDI to Microsoft over Amazon Web Services last year. An Amazon blog post this morning said that “We asked multiple times for clarification, to which the DoD was unresponsive…. This could have been easily avoided if they had chosen to be responsive in any of the multiple requests we’ve made in the last two weeks.”

Charles Tiefer

But wait a minute. If the Department of Defense didn’t respond to Amazon’s satisfaction on repeated prior occasions – actually going back to Amazon’s original request last year for a debriefing on why they lost the contract in the first place – DoD was hardly going to change course just because Amazon filed this protest, and Amazon’s lawyers had to know that, one would think.

In fact, agency protests have no legal force and rarely get the agency to do anything, said Baltimore University law professor and former congressional counsel Charles Tiefer. “Agency protests are generally not made on their own because they are such a long shot,” Tiefer told me. “Rather, they are a step in the process of going to court or to the GAO.”

In effect, an agency protest puts the protesting company on record that it objects to how the contracting agency handled the award. That way the company’s lawyers can tell Congress’s Government Accountability Office and/or a federal judge that they tried and failed to get the agency to fix the problem before they escalated the matter to the GAO or the court.

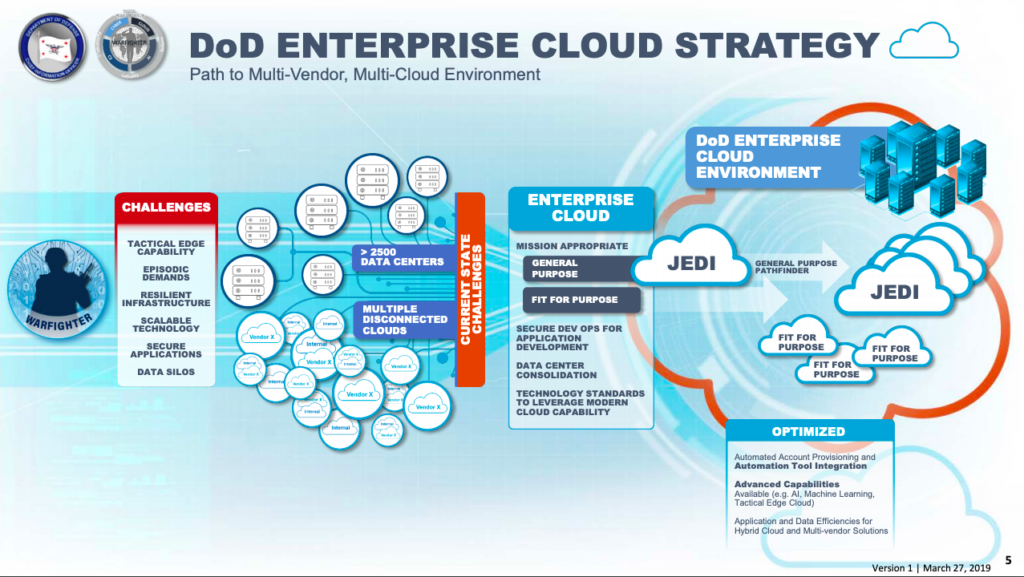

The Pentagon’s plan to consolidate many — but not all — of its 500-plus cloud contracts into a single Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI).

But last fall, when the Pentagon awarded the Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure contract – worth up to $10 billion over 10 years – to Microsoft in an upset victory, Amazon went immediately to court. That skipped what’s normally Step 1, an agency protest, and Step 2, a GAO protest. So why file a protest now?

In fact, once you escalate to GAO or the Court of Federal Claims, you normally can’t go back and file an agency protest. As an authoritative Congressional Research Service report put it in 2018: “Interested parties that disagree with GAO or procuring agency decisions generally can still bring claims before the COFC, whereas the reverse route is generally not permitted.” (Emphasis ours).

But in this particular case – and it’s a strange case indeed – Amazon did have a new opportunity to file a protest, because the Defense Department has taken a new action.

“Think of this as a subroutine within a large, complex software program,” said Andrew Hunter, a former Pentagon acquisition official now at thinktank CSIS. “AWS is exercising all of its rights within the ‘subroutine’ process even as it litigates at the Court of Federal Claims on the entire program.”

Specifically, having admitted that it messed up one narrow, highly technical portion of the award process known as Price Scenario Six, DoD won the judge’s permission for a do-over of that specific scenario. (Amazon had objected to the other scenarios as well). Part of that do-over involved Amazon and Microsoft both submitting revised bids for Price Scenario Six. But Amazon says DoD “didn’t clearly define… the new [data] storage requirement,” even when Amazon repeatedly asked them for clarification. Hence the protest.

Here’s all the Pentagon would say publicly on the matter: “DoD continues to execute the procedures outlined in the Motion for Voluntary Remand [i.e. the do-over] granted last month with the intent of delivering this critically-needed capability to our warfighters as quickly as possible.”

The studious blandness of that statement should be no surprise. Again, Amazon’s protest isn’t really about getting the Pentagon to change its mind, but about what Tiefer calls “due diligence” in getting its objections on the record for the judge to see.

Andrew Hunter

“Protesting the revised evaluation of Price Scenario Six officially registers that AWS believes that the evaluation process is still unfair,” Hunter told me “If they didn’t protest the evaluation criteria now, it could be presumptively deemed that they accept the new terms as fair.”

There’s one more weird wrinkle to this story, however. Microsoft promptly published its own blog post and was, in fact, the first to mention the protest in public. Since agency protests are confidential, it’s actually unclear if Amazon or DoD intended to make this public prior to Microsoft announcing it.

You see, unlike protests to GAO or the Court of Federal Claims, agency protests are not public record, they’re confidential. When Microsoft objected to Amazon’s protest being “out of view of the public,” well, that’s how agency protests are supposed to work. “There are no comprehensive publicly available data on protests before procuring agencies,” CRS wrote, “[and] agency protest decisions are not published.”

In fact, agency protests are often resolved completely in confidence between the protester and the agency, although in some cases competing bidders have to be notified. Microsoft’s blog post says “We received notice on Tuesday that Amazon has filed yet another protest.”

Now, Microsoft didn’t reveal the confidential content of Amazon’s protest – in fact the blog post says they haven’t seen it – just the fact that it exists. And, as far as I know, it is not illegal for Company A to publicly discuss Company B’s agency protest, even if Company B hasn’t said anything publicly itself. But it is definitely unusual.

For the Byzantine battle over JEDI, however, “unusual” has become the new usual.

‘The bad day’: DISA’s forthcoming strategy prepares for wartime coms

“It’s great to have internet day to day in peacetime,” said Lt. Gen. Robert Skinner, director of the Defense Information Systems Agency, “but it’s more imperative to have it when bullets are flying.”