WASHINGTON: The Defense Department will release a draft Request For Proposals next month, asking the private sector for ideas on how to apply 5G network technology to military purposes — including fixing glaring security problems with the new technology. After getting feedback from industry, the Pentagon will revise the RFP and issue a final version in December – that is, officials caveat, if Congress passes the currently-gridlocked 2020 funding bills in time.

While the Pentagon has many uses in mind, one constant across all of them must be cybersceurity, said the Deputy Under Secretary for Research & Engineering, Lisa Porter.

Lisa Porter

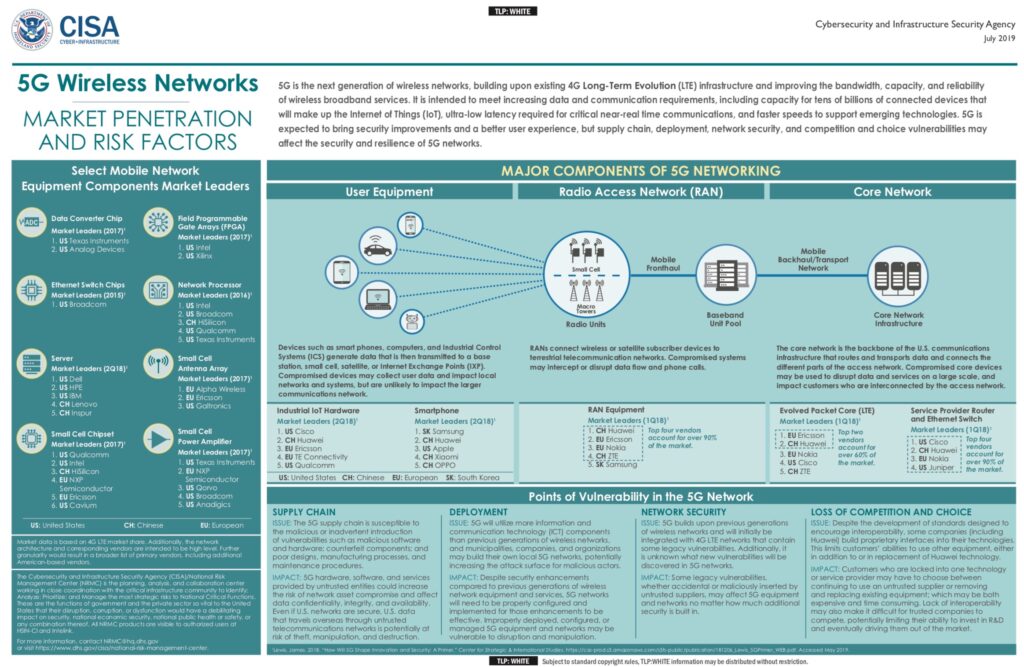

“A big part of what we want to make sure we do is piece together with industry how we address the vulnerabilities that are going to emerge in 5G,” she told reporters in a conference call. “5G is really ultimately about ubiquitous connectivity, right, it’s not just cellphones and cat videos, it’s really everything getting connected to everything else.” This internet of things has huge potential for both civilian and military applications, she said, but “there’s going to be a lot of complexity. With complexity comes much greater attack surfaces.”

Porter announced the proposal this morning at Mobile World Congress ‘19 in Los Angeles. It’ll be a step by step approach, she emphasized, starting with experimental pilot projects at four Defense Department installations on US territory. (Which ones, she wouldn’t disclose). Those first four sites would conduct experiments in one or more of three “use cases”:

- Virtual and augmented reality for training and mission planning. The Army in particular is exploring large-scale “synthetic” training exercises, with numerous users interacting with each other and simulated enemies, both in purely virtual environments and while moving around in the real world. (Think Pokémon Go, only with enemy soldiers superimposed on your field of vision instead of cartoon monsters). That requires a network with unprecedented bandwidth, something 5G technology is meant to deliver.

- “Smart warehouses” that use 5G networks to track supplies. Ever since mislabeled shipping containers went missing in the massive iron mountains built up in supply dumps for the first Gulf War, the military’s been interested in radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags to track shipments. But manually scanning the RFID tags and recording what each says is a labor-intensive process, making an automated, networked system more attractive.

- “Dynamic spectrum sharing” between different military functions – for example, Porter said, between wireless communications networks and radar, which both use mid-band radio frequency transmissions – and even between the military and the commercial sector. Historically, the US has allocated specific blocks of frequencies in specific geographical areas to one and only one user, be that a public agency or a private entity: If the designated user isn’t transmitting at a particular time, no one else is allowed to use the idle frequencies. That inefficiency is becoming untenable as more and more wireless devices demand more and more spectrum to transmit and receive, pushing both industry and the military to explore constantly re-allocating frequencies to whoever needs them most at the moment, much like an air traffic controller sends different airplanes to different altitudes to avoid collisions.

Subsequent “tranches” of the project will bring in more Defense Department sites, potentially including some overseas while exploring additional use cases Porter told reporters. “We’re going to be rolling this out in tranches [and] learn as we go,” she said.

So far, Porter said, it’s the spectrum-sharing initiative in particular that has “gotten a lot of attention.” Industry is especially excited at the idea of potentially time-sharing some of the precious mid-band frequencies currently reserved for military use.

Mid-band lies at a sweet spot on the spectrum, with frequencies high enough to transmit lots of information fairly quickly – bandwidth – and wavelengths long enough to penetrate most obstacles. (The higher a transmissions’ frequency, the shorter its wavelength, and vice versa). By contrast, low-band transmissions have longer wavelengths that penetrate obstacles even better, making them highly reliable connections, but their frequency is so low they transmit information at a very low rate. Meanwhile, 5G is now opening up the possibility for high-band millimeter wave frequencies that can transmit vast amounts of information per second, but their wavelengths are so short they’re easily stopped by obstacles, like “the roof of your car or a rain cloud,” as HowToGeek.com puts it.

The Defense Department has already sought input from a host of companies, Porter and Pentagon 5G tech director Joe Evans said, representing the whole “ecosystem” from makers of microelectronics to major service providers. It’s even created a special outreach office to work with the private sector on 5G. And in an earlier Request For Information (RFI) that went out through the National Spectrum Consortium, Evans said, “we received over 260 responses laying out ideas.”

That’s the scale and enthusiasm the Pentagon is hoping to tap into for this new 5G project, so the US can catch up to global leaders in the field – like China.

Advancing military training with VR and simulators

Our latest eBook offers a glimpse into cutting-edge VR, simulators & military training tech showcased at I/ITSEC 2024 in Orlando.