HARTFORD, CT: Aircraft engine maker Pratt & Whitney proudly predicts it will double its revenues this decade from $12 billion in 2010 to $24 billion in 2020 — but the company admits it will have to get through some lean years first. On both the commercial and military sides, key Pratt & Whitney programs are going away, and new engines using new technology for new aircraft are coming online, but there’s a gap before they pick up, a gap that slow economic growth and downsizing defense budgets threaten to lengthen. The single most critical factor: whether the troubled F-35 Joint Strike Fighter materializes more or less on time.

“We are in a little bit of a transition period…going from legacy engines to new engines,” Pratt & Whitney President David Hess told reporters at the company’s annual media day. “We just have to navigate through a couple of transitional years here.”

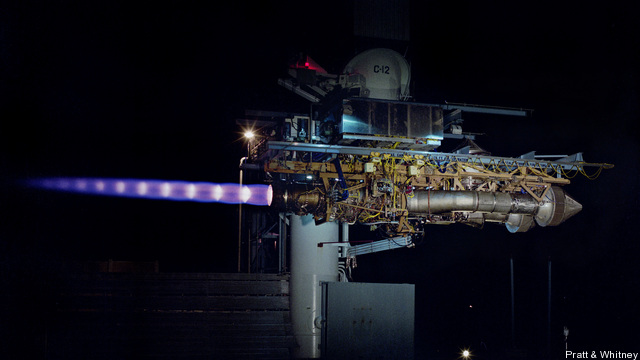

Consider fighter engines. This year, Pratt & Whitney will deliver its last F119 engine, for the F-22 Raptor stealth fighter, whose production run has already ended (that last engine will be a spare). Sales of its stalwart F100, used on both the F-15 and F-16 fighters, are beginning to decline. The company’s counting on the next fighter engine coming along, the F135, used on all three variants of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. Pratt & Whitney will deliver about 50 this year, ramping up to 250 around 2018; but the Pentagon has already slowed down the rate it buys the airplane — and thus of course the engine — both to save money in the short term and to give more time to work out development problems.

Similar gaps threaten for both commercial airliner engines and commercial derivative engines for military support planes. Production of the V2500 jet engine for commercial airliners will wrap up circa 2018, and the company’s bet heavily that its new, more fuel efficient “geared turbofan” technology will take the airline market by storm. On the military side, the last F117 engine for the C-17 cargo jet is currently scheduled to be built circa 2015, and a new commercial-derivative engine, for the Air Force’s KC-46 tanker, won’t ramp up until two years later.

Besides, “there’s four engines on a C-17 and only two on the tanker, so even if [the numbers of airplanes were] the same, it would still be half the value for Pratt & Whitney,” said Military Engines president Bennett Croswell in an interview with Breaking Defense. That said, Croswell went on, “we’ve been thinking the C-17 was going out of production for a long time and people keep buying it because it’s such a capable airplane; last year India announced their intent to buy ten.” The 2015 end-date reflects only current orders, he said, and “there’s other opportunities we continue to seek.”

Croswell’s division will also go after Army helicopters; the service is seeking new engines for its mainstay Apaches and Black Hawks, whose currently powerplant was designed in the 1970s, a project that might potentially extend to replacing thousands of engines already in service. At the moment, though, the Army is still in the technology demonstration phase, with Pratt & Whitney, its partner Honeywell, and arch-rival General Electric waiting for an actual competition to start.

No matter what happens on military tankers, transports, and helicopters, the crucial question remains the Joint Strike Fighter. Pratt & Whitney’s big win on that program this past year was the (apparently) final defeat of Congressional efforts to make the Pentagon pay GE to develop an alternative engine, on the model of the competing Pratt & Whitney and GE engines available for the F-16. The Defense Department argued strenuously and successfully against spending government money to develop such a backup for the F-35.

“The taxpayer finally prevailed and the DOD customer finally got what they wanted with the elimination of the extra engine for the Joint Strike Fighter program,” crowed Hess. “The military engine business looks great for us because we’re on the right program [and] we’ve got the sole source position on the Joint Strike Fighter,” which he expects to be “a big growth engine for Pratt & Whitney… regardless of where the [Congress] ends up on sequestration and the budget cuts.”

The prospect of sequestration nevertheless hangs ominously over Pratt & Whitney, just like every company with government contracts.”Because our customer’s not planning for it, I don’t really know how they would react to that [sequestration],” Croswell said frankly. “If you look at the new defense guidance that says the way the country is primarily going to project power in the future is via sea and air forces, you would think that future budget cuts would potentially do less damage to those kinds of systems” — i.e. protecting aircraft budgets at the expense of, say, ground forces — “but the sequestration [approach,] it’s a meat cleaver to the whole DoD budget,” Croswell said. “Hopefully, saner heads will prevail.”

Sullivan: Defense industry ‘still underestimating’ global need for munitions

National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said that there are “no plans” for another Ukraine supplemental at this point.