On July 10, the U.S. Navy released a request for proposals for the first all-new electronic jammer in over 40 years.

On July 10, the U.S. Navy released a request for proposals for the first all-new electronic jammer in over 40 years.

It’s about time since the existing ALQ-99 jammer carried on electronic-warfare planes is gradually losing the ability to keep up with joint requirements — not to mention threats.

When the ALQ-99 debuted in 1971, digital datalinks, cell phones, no frequency-hopping radios, monopulse radars and improvised explosive devices did not exist. Today, those innovations dominate the threat environment, and explain why the Navy no longer thinks it can get by with additional upgrades to a system designed in the age of vacuum tubes.

Among other things, the existing jammer cannot cover all the frequencies that need to be addressed, cannot radiate sufficient power to jam remote emitters, cannot negate a sufficient number of simultaneous threats even in the bands where it is effective, and cannot operate with the spectral precision required to avoid degrading friendly communications.

The new Navy program is important to the entire joint force because the other services have dropped the ball on electronic warfare. The Air Force thought it could assure aircraft survivability with low-observable (“stealth”) technology, so it retired Cold War planes used to jam enemy radars. The Army became distracted by the battle in Southwest Asia and ended up killing the airborne-sensor program that would have modernized its ability to identify hostile emitters. The Marine Corps understood the value of electronic warfare, but wasn’t willing to pay for modified F/A-18 Super Hornets that could host a new jammer.

So the Navy has become the main repository of electronic-warfare expertise in the U.S. military. It has developed a replacement for its decrepit EA-6B Prowlers, designated the EA-18G Growler, and modernized some features of the electronic attack mission in the process, but the new plane is carrying aged ALQ-99 jamming pods into a future where they will be woefully inadequate.

Add to that the cost of maintaining antique technology in an age when many of the original suppliers have disappeared, and it’s easy to see why the ALQ-99 has to go. The question is what kind of system should replace it. In the near term, the Navy needs a more capable jammer that can be hung on the Growler and aging Prowlers operated by the Marine Corps. Later on, it will need to adapt that jammer to the F-35 fighter that will be operated by the sea services in the future, and, later perhaps, to unmanned aircraft.

So the design of the new jammer will have to be flexible because it will eventually need to fit into a variety of dissimilar airframes. Flexibility is also dictated by the pace at which threats, missions and relevant technologies are evolving. The Next Generation Jammer is supposed to remain in the joint force for 40 years once it becomes operational at the end of this decade, which in technological terms will probably mean for six or seven generations. So the system needs to be designed for continuous modification and upgrades — a modular, open-architecture design that can accommodate whatever joint requirements arise.

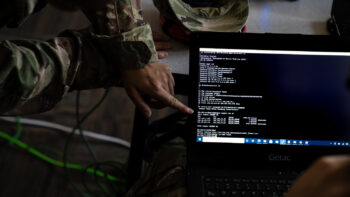

Some of the likely features of the new architecture are obvious. For instance, the mechanically steered antennas that currently aim jamming signals will need to be replaced with electronically steered antennas that have fewer moving parts. Power sources will need to be much more robust, and techniques for venting excess heat will need to be improved. But there are literally hundreds of technological options to consider, such as substituting reconfigurable software for hardware as a way of saving weight.

The Navy has given several hundred million dollars to four industry teams to work on technologies that might be useful in the new jammer. Its July 10 solicitation signals that the service is now ready to move on to the technology-development phase of the program in which the best teams and ideas go forward while the losers must face a prospect of little future in the electronic-warfare business. The outcome of the “down-select” expected in fiscal 2013 might well begin a process of consolidation in the overcrowded military-electronics sector, where too many companies are chasing too little future demand.

All of the companies leading teams — BAE Systems, ITT Exelis, Northrop Grumman and Raytheon — are highly qualified. BAE, heir to the legendary Sanders Associates EW franchise, and Northrop Grumman, successor to the old Westinghouse Electronics, are generally deemed to be the strongest contenders. But so much has changed in the military-electronics business since the ALQ-99 first flew that any of the companies could win. A standard government strategy in such down-selects is often to pick one contender that is certain to deliver, and another that offers something new and exciting. If the Navy goes that route, it could confound the conventional wisdom on who the winners will be.

Whoever wins, it is essential that the Next Generation Jammer stay on track come sequestration or whatever, because the survivability of the joint force hinges on acquiring a more versatile jammer. There are too many hostile emitters appearing, from agile radars to 4G smart phones, to continue relying on a jamming system designed when Richard Nixon was in the White House. The joint fleet is full of combat aircraft that can’t survive without standoff or escort jammers, and nobody knows for sure when stealth aircraft currently in development will replace them. The Next Generation Jammer thus plays a pivotal role in determining whether America can maintain global air dominance through midcentury.

The Navy’s never-ending quest for 355 ships: 5 Navy stories from 2024

Ship counts were clearly on the mind of US Navy officials this year as they made numerous plays to bolster the fleet in novel ways.