WASHINGTON: Denmark really wants you to know they have a solution for the US Navy’s frigate problem. Pentagon officials are on the record that they’ll consider foreign designs in their quest for a more powerful small warship than the $450–$550 million, 3,400-ton Littoral Combat Ship. The Danish answer: their $340 million, 6,600-ton Iver Huitfeldt “Stanflex” frigate.

That’s a lot of ship for the price. But a leading US expert, Bryan Clark, tells us that the Danes may be undercounting their costs by about $50 million, since some of the frigates’ weaponry was recycled from older ships going out of service — an economy made possible by the Danish navy’s Stanflex system of interchangeable equipment modules. That would put the frigate at under $400 million, which is still pretty good compared to LCS or international competitors. The thing is, Clark argued, the costs to the US would be much higher once the design was upgraded to US Navy standards, fitted with US weapons and electronics, and built in less efficient US yards.

With a new radar and other upgrades, “the ship would likely cost around $700-900 million, which would be similar to the (Franco-Italian) FREMM, an upgraded LCS, and the (Spanish) F-105,” said Bryan Clark, a former top aide to the Chief of Naval Operations. “It would probably be a little higher than (an upgrade of the Coast Guard) National Security Cutter.”

The two US and two European designs Clark listed are the ones I wrote up in May as the four top contenders for the frigate contract. I barely mentioned the Iver Huitfeldt in that story because no one could name a US shipyard interested in working with the Danes on the design, while the FREMM and F-100/F-105 series had clear potential partners. After that story appeared, however, the Danish embassy reached out to me to argue they are very much in the running.

Odense Maritime Technology (OMT) owns the design, said Rear Adm. Niels Olsen, the Danish defense attache here, and “they have already been in contact with Ingalls and Bath” — the two US shipyards that build destroyers.

“And they have been in dialogue with Lockheed,” added Olsen’s assistant attache, Lt. Col. Per Lyse Rasmussen. Lockheed builds the Freedom-class Littoral Combat Ship with Wisconsin shipyard Marinette Marine, which is owned by Italian defense firm Fincantieri — which incidentally builds one of competing frigates, the FREMM. Rasmussen said, “Lockheed Martin seems interested, Fincantieri maybe not so much.”

The Danish Navy also took the opportunity to show off the ship when the second frigate in the class, Peter Willemoes, visited the US in November. The chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, Rep. Mac Thornberry, toured the ship, as did the Chief of Naval Operations, Adm. John Richardson. Olsen noted proudly that both men were “very impressed.” There were also visiting representatives from the Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA), which oversees all naval shipbuilding, who “took many, many notes.” Overall, Olsen said, “we had several US admirals on board, and many of them have since followed up with questions.”

“We don’t expect you to buy ships and build them in Denmark or anything, but you should at least look at the design and see smart, smart stuff” that’s worth copying for future US ships, Olsen said. “You’re also welcome to buy the design,” he added with a chuckle.

What’s in a Frigate?

The Iver Huitfeldt frigates are built for “hard warfighting,” Rear Adm. Olsen said. Equipped to combat hostile ships, aircraft, and submarines, he said, “they’re able to fight in all three dimensions simultaneously.” With numerous watertight compartments, kevlar linings, and shock-proof mountings for all key equipment, he went on, “they can take a hit and they can keep on fighting.” In fact, one of the frigates recently passed the Royal Navy’s Flag Officers’ Sea Training (FOST) program with distinction, which includes a notoriously tough six-week wargame with intensive damage-control exercises.

Olsen was too polite to say so, but survivability and damage control have been consistent concerns about the Littoral Combat Ship. LCS is automatically disadvantaged as a small ship with less metal to take a hit and fewer sailors to do damage control. What’s more, LCS is made at least partially of aluminum, which has a nasty tendency to catch fire if hit by missiles: The Lockheed/Marinette Freedom class has an aluminum superstructure, while the Austal Independence variant has an all-aluminum hull. The Iver Huitfeldt frigates are all steel.

Offensively, the Danish frigates hit much harder than LCS as well. The Iver Huitfeldt mounts a pair of 3″ (76 mm) deck guns — considerably heavier than the single 57-mm gun on LCS — with space and structural support to upgrade one weapon to a standard US Navy 5-incher. They have 16 Harpoon anti-ship missiles, similar to the Over The Horizon (OTH) missile that will be added to the LCS. And, unlike LCS, they have full-size Vertical Launch System (VLS) silos that can launch a variety of anti-aircraft and missile defense weapons — or, if the Danish government were to buy them, offensive missiles such as the Tomahawk.

It’s how much the Danish government pays for this firepower that generates debate. A 2015 article on the CIMSEC naval affairs blog called the Iver Huitfeldt class a “Danish strawman” that had been delivered without key equipment, but Olsen told me that was done merely to get sea trials started ASAP, and the ship is now fully armed and operational.

Fully equipped, an Iver Huitfeldt frigate costs the equivalent of $340 million, Rear Adm. Olsen said. Most of that, about $207 million, goes to weapons, sensors, and other electronics, which drive the cost of modern warships worldwide. The hull, engines, and other mechanical systems (HME) only cost about $133 million — although Olsen acknowledges it would probably cost more in a US shipyard than it did in Maersk’s Odense shipyard, which has since been closed in any case.

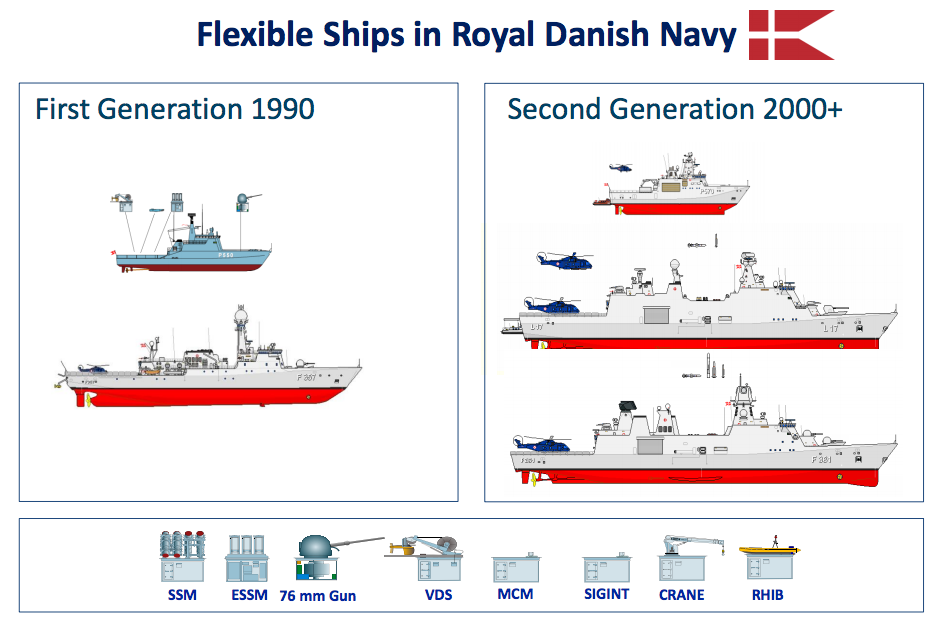

Central to the cost-efficiency is the Stanflex system of modular weapons and sensor packages. Pioneered on Danish patrol craft in the 1990s, Stanflex ironically inspired the “mission modules” on the US Littoral Combat Ships. While the LCS modules are now behind schedule and as controversial as anything else in the program, the US Navy is still intrigued by how modularity can ease both initial construction — the Iver Huitfeldt frigates were built in Maersk’s low-overhead commercial shipyard, their weapons added later — and subsequent upgrades — which can be as simple as swapping in more modern modules.

“We separated the platform and the payload,” Rear Adm. Olsen said. He likened the Stanflex ships’ ability to swap modules with a smartphone’s ability to download new apps: In both cases, you don’t need to anticipate all your needs and hardwire them into the platform, you just need a standard interface into which a wide variety of options can plug. That eases maintenance, mission changes, and updates with new technology.

The frigate is built to military standards for damage control, Olsen emphasized, but it uses civilian systems to save cost wherever their performance is acceptable. “In fact, a lot of civilian stuff is pretty good,” he said. “They can in some cases withstand a lot more punishment than some military stuff.”

Bryan Clark was unconvinced. “The Iver Huitfeldt uses mostly commercial components that may not be rated for the run time” — the sheer wear and tear of long deployments — “and potential effects of (battle) damage that US ships are expected to experience,” he told me. “US Navy ships have a much higher OPTEMPO (operational tempo) than foreign ships, are expected to operate in a higher threat environment, and are expected to return to service after a casualty (accident or battle damage) and repairs.”

“A ship built to U.S. military standards will have more hull stiffeners, more compartments, redundant wiring and cabling, etc. – all of which add man-hours to ship construction times,” Clark said. All told, he said, “I’m confident that a ship built to some version of US military standards will be more expensive.”

Even if the original design is good, said naval historian Norman Polmar, the US Navy and Congress will want to replace contless foreign components with ones made in the USA. “Steel for hulls is the cheapest part of the ship; it’s the electronics, the weapons, and the machinery that cost,” he said, and that’s what the Navy would change.

Polmar likes the Iver Huitfeldt class — “It’s an excellent design” — but he says the US Navy hasn’t bought a foreign warship design since World War II. With the protectionist Donald Trump in office, he added, we’re not going to start now.

That’s a challenge that the Danes — and the French, Italians, and Spaniards — aim to overcome.