Chinese aircraft carrier Liaoning

It’s one of the fundamental questions about China and its future place in the world: does the great civilization still view the world through the traditional lens of the Middle Kingdom, or does the world face a new China, unbound by many of the structures under which it has operated for most of the last 2,000 years? The answer offered here is by Dickson Yeo, a Singaporean scholar steeped in Chinese history, culture and politics. Dickson is a Ph.D candidate at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. Read on! The Editor.

Even as as China marches towards economic dominance in Eurasia, the realities of global competition have created a briar patch for China’s central planners.

Historically, China’s Confucian planners have preferred to view the world through a Middle Kingdom paradigm, favoring self-sufficiency and a coordinated economy which sought to expand domestic production. But the struggle for natural resources and global chains of supply have forever shattered this structure, forcing Beijing to rethink its model.

China’s position as the world’s leading factory forces it to rely on markets across the Indo-Pacific for raw materials. At the same time, Beijing has utilized the West (especially US markets) to revitalize its economy since 1978. Further downstream, rapid takeoff economies like India and Vietnam are reliant on the Chinese giant. It’s with this globalized view that Beijing must find access to resources, tech and market-share throughout Eurasia. Given the historical experience of the West in securing raw materials, there are growing suspicions that Beijing will become another old-time colonial power in the developing world. This is far removed from the historically self-sufficient Middle Kingdom model that China prefers.

Chinese President Xi Jinping inspects PLA troops

While the Belt and Road initiative continues its steady rollout in Eurasia, there’s active push-back by many of the ASEAN states. This seems to ensures that the BRI and its financial arm, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, will not be dominated by Beijing. Instead, China will have to bargain and accept significant costs with regional states as it scrambles to guarantee resources and markets beyond its immediate neighborhood. As its reliance on foreign commodities increases, China will increasingly build a military capable of force projection that will be exacerbated by pushback by regional powers like India, Japan, Vietnam and Indonesia. To a suspicious West, this should be comforting.

China’s well-known Silk Road initiative is less than a decade old, and the US-educated Asian elite is not clear on how China’s opaque system allows for lobbying and resolving conflicts. Before the recent Huawei scandal and the US Justice Department’s legal actions against the Chinese tech giant, Germany and the Scandinavian economies had begun to limit Chinese participation in infrastructure and M&A activities, with the view that there is no distinction between Chinese corporate and Communist Party shenanigans.

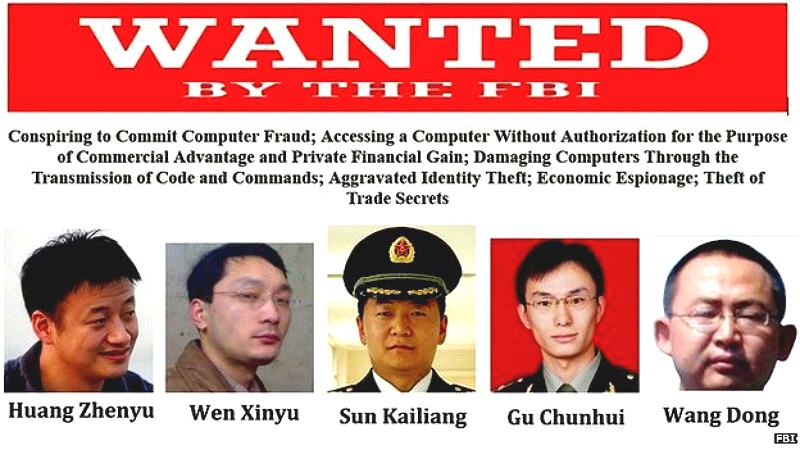

If baseline trust in data sovereignty and absence of cyber-espionage activity cannot be guaranteed, most of China’s new BRI partners are likely to seek safeguards from the West’s institutions and systems — the liberal international order — by working with neighboring economies like Japan or the UAE so they can preserve economic decision-making independence while they dance with the dragon.

The OECD operates in such a way that actively pushes the advantage of their flag-bearing firms overseas. The global corporate sector, has prime economic leadership in their respective home countries and act as economic vanguards abroad. The need to secure the Fortune 500’s market position in the Indo-Pacific, had led American institutions to proactively tailor policies to suit this form of market competition abroad.

The backlash against economic globalization as shown populist electoral victories and the British vote to leave the European Union has only hardened the resolve to protect these transnational champions in the West. The free-flowing nature of technological innovation and the difficulty in policing intellectual property transfer means that Beijing is ramping up its own domestic innovation in response and increasing its support for national champions like Huawei overseas.

The persistent model of the Middle Kingdom granting preferential access to foreign merchants in exchange for benefits cannot exist in this context where domestic flagbearers compete in an increasingly competitive global economic environment. Today appears to be more like the 18th century’s rise of transnational firms that carved out market space for smaller players at home and guaranteed access to virgin markets in Asia and Africa. The old days of state-sanctioned pirates may be over, but their modern equivalents of hacking, cyber-theft and espionage have risen to take their economic place.

The Huawei debacle is only act one of an unfurling global corporate contest where China’s flag-bearing corporate giants will battle the Fortune 500. The power of multinational corporates is beginning to surpass that of their respective nation-states. There is growing alignment between the management of national bureaucracies with mainstream corporate governance. The outsourcing of major governmental functions to transnational consultancies and service providers has elevated the MNC paradigm in at least the OECD.

Once again the similarity to the old mercantilist trading empires of Europe is uncanny. But China’s political elite insist there will be no rehash of the high-colonial invasion of Britain’s East India Company or the Dutch VOC; China will hold its own in this new Great Game.

Israel signs $583 million deal to sell Barak air defense to Slovakia

The agreement marks the latest air defense export by Israel to Europe, despite its ongoing war in Gaza.