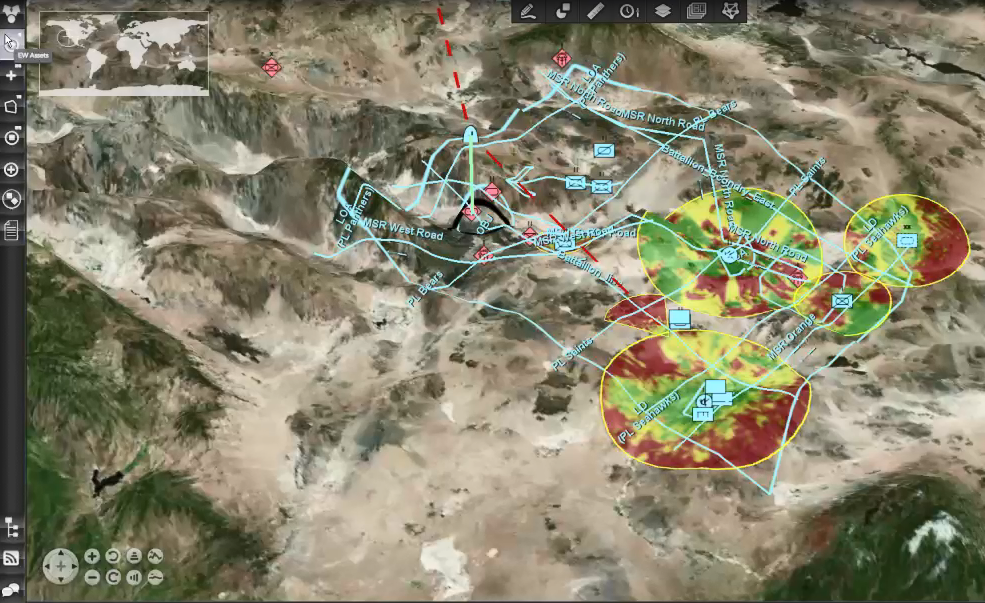

Screenshot from an early version of Raytheon’s Electronic Warfare Planning & Management Tool

ARLINGTON: After five years of development — and urgent fielding of partial versions to troops in Europe and elsewhere — Raytheon just got the contract to complete the command-and-control software for the Army’s rapidly expanding electronic warfare corps, EWPMT.

The Electronic Warfare Planning & Management Tool is designed to get emissions, analyze them and make attack recommendations. How? It scrapes data from sensors across the battlefield, synthesizes it all into an intelligible map of where signals are getting through and where they’re being jammed, and simulates the effects of potential countermeasures so commanders can make an informed decision on how to counter the enemy. Over the next two years, Raytheon will receive an unspecified “multi-million dollar” sum to develop and field what’s called Capability Drop 4, upgrading the EWPMT software to its official Fully Operational Capability (FOC) by October 2021.

Soldiers using the Electronic Warfare Planning & Management Tool (EWPMT) in the field

Capability Drop 1 was the initial basic version for Army electronic warfare officers, Raytheon exec Niraj Srivastava told reporters this morning at a company briefing ahead of the annual AUSA mega-conference. CD 2 added spectrum-management functions to help deconflict friendly transmissions and keep US forces from accidentally jamming each other (which happens a lot). CD 3, now fielded with select units in Europe and other locations the Army won’t disclose, adds the capability to take in data from sensors in real-time, plus much more automation and analytics. (An early, slimmed-down version of CD was deployed under the codename Raven Claw).

What’s next? “With the fourth capability drop, we are bringing a lot more automation and machine learning/AI” to translate raw system data into a real-time picture of signal strength and interference across the battlefield, Srivastava said.

They’re also upgrading the software to work with a wider range of third-party sensors. “We just finished an exercise last month where we had about a dozen different industry partner sensors, from UAVs to terrestrial vehicles to man-mounted systems,” he said. Those sensors can either be plugged directly into the computer running the EWPMT software — which means that data is displayed, for all practical purposes, instantly — or connect over a wireless network — which allows the user to access many more sensors over a much wider area at the potential price of lag and interference.

EWMPT is an obscure piece of Army modernization compared to robot tanks and high-powered rifles. (You really know an Army program has been overlooked by the top brass when its acronym doesn’t spell out anything cool or pronounceable). But it’s a critical element of modern conflict. Russia in particular has used its mastery of electronic warfare to great effect against Ukraine, leading GPS astray with false signals, targeting Ukrainian troops for artillery barrages by tracking their radios and cellphones, and baffling US sensors in Syria.

Electronic warfare may be invisible to the human eye but the Army has sensors that can detect these transmissions. Doing something with that information has historically been a laborious process involving Excel spreadsheets, PowerPoint slides, and lots of yellow sticky notes. That leaves precious little time to actually think about what to do and make a plan.

EWPMT is intended to automate the process, giving electronic warfare troops a clear picture of what’s happening and what they can do about it. The heart of the software is a physics model that uses data from multiple sources to calculate how radio waves are interacting, or could interact, both with each other and the terrain. (Hills and buildings often block transmissions).

Army Tactical Electronic Warfare System (TEWS) at the National Training Center on Fort Irwin, California.

That model doesn’t care where its inputs come from or where its outputs go, Srivastava explained. So, using what’s called open architecture, it’s relatively straightforward to add a new software module to take in data from a new sensor, he said, or to alter how the data is displayed on the screen for different missions and users, or to transfer that data to other military systems.

For example, once EWPMT has figured out where jamming is coming from, it can share that location with the Army’s artillery fire control software, AFATDS, allowing the nearest howitzer battery to blow the enemy transmitter up. So the US Army will be able to do what Russia has been doing against Ukraine.

EWPMT will also be able to pass data to the Army’s own long-range offensive jammers, so they can disrupt hostile transmissions that can’t or shouldn’t be physically destroyed. The problem is most units won’t actually get those jammers for years to come.

The Army has a handful of prototype and experimental systems for offensive electronic warfare, many mounted on Humvees, MRAP trucks, or 8×8 Stryker armored vehicles. But the official Programs Of Record, the equipment that will actually be mass-produced and issued across the Army, won’t begin fielding until 2022-2023. Those would be the land-based Terrestrial Layer System (TLS) — formerly Terrestrial Layer Intelligence System because it includes SIGINT capabilities — and the drone-mounted Multi-Function Electronic Warfare – Air (MFEW-Air).

EWPMT Capability Drop 4 will have the capability to connect with both these systems, Srivastava said, but they won’t be in service until some time after it enters service in 2020-2021.

Move over FARA: General Atomics pitching new Gray Eagle version for armed scout mission

General Atomics will also showcase its Mojave demonstrator for the first time during the Army Aviation Association of America conference in Denver, a company spokesman said.