PENTAGON: After decades of wasting billions on a long list of cancelled programs, the Army is finally building momentum on modernization. But if Congress can’t pass policy and funding bills for the fiscal year that began Oct. 1st, the new Army Secretary warned, “it could potentially stall us out.”

PENTAGON: After decades of wasting billions on a long list of cancelled programs, the Army is finally building momentum on modernization. But if Congress can’t pass policy and funding bills for the fiscal year that began Oct. 1st, the new Army Secretary warned, “it could potentially stall us out.”

“We have to get this budget deal,” Ryan McCarthy told me during an interview in his E-ring office here.

Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy

For McCarthy — an Army Ranger who went on to serve as a Congressional staffer and a senior aide to acclaimed Defense Secretary Robert Gates under both Bush and Obama – this is a Jerry McGuire moment. With a few significant exceptions, such as undoing the cancellation of the CH-47F helicopter and cutting Army VR simulations, Congress has been highly supportive of Army modernization. Now McCarthy’s asking legislators, show me the money.

Just before our interview, he’d spent the morning on Capitol Hill with the Senate Army Caucus, bringing a whole delegation of Army leaders to help make his case, and he plans to head back to the Hill next week.

The situation is sufficiently dire that the Republican chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, Jim Inhofe, announced this morning that he would introduce a “skinny bill” to “ensure that Congress is able to extend necessary authorities, take care of our troops and their families, authorize military construction projects, and conduct oversight over military acquisition programs,” while he and his House counterparts thrash out the full National Defense Authorization Act. [UPDATE: The Democratic chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, Rep. Adam Smith, almost immediately rejected the idea of a skinned bill.]

But the NDAA is the defense policy bill, which simply authorizes the Pentagon to do things. The actual money to pay for doing things comes from the annual defense appropriations bill. That vital piece of legislation doesn’t even have a floor vote scheduled in the Senate, although Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has pledged to send it to the floor after four domestic appropriations bills scheduled for votes this week.

Currently, the Pentagon is on autopilot, along with most civilian agencies, under what’s called a Continuing Resolution. A CR sets spending at last year’s levels – so, without hard-to-get exemptions called “anomalies,” it’s illegal to start a new program, cancel an old one, ramp up production, or stop buying so much of something the military doesn’t need.

In the Army’s case, McCarthy’s staff told me, even a further short-term CR would prohibit starting six new procurement programs, including the S-MET robotic transport and new navigation equipment, and 11 new research efforts, including for future ground vehicles, missiles, artillery, and soldier kit. It would also forbid planned production increases for 13 programs, from new UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters to upgraded Stryker armored vehicles. A longer-term CR – including the full-year CR some in Congress are contemplating – would stall 29 procurement programs, including much-needed air and missile defense capabilities, 31 research efforts from hypersonics to cyber warfare, and 37 production increases, including many precision-guided weapons in short supply. Training exercises would suffer as well, reducing readiness for any near-term conflict.

Extended, edited excerpts from our interview with Sec. McCarthy are below.

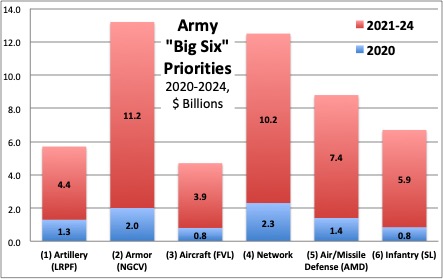

LRPF: Long-Range Precision Fires. NGCV: Next-Generation Combat Vehicle. FVL: Future Vertical Lift. AMD: Air & Missile Defense. SL: Soldier Lethality. SOURCE: US Army. (Click to expand)

Sydney Freedberg, Breaking Defense: You are moving into crunch time for Army modernization programs, because a lot of this stuff is now moving from PowerPoint to actual demonstrations, to prototypes, to production.

Ryan McCarthy, Secretary of the Army: You framed it quite well. In ’18 and ’19 we were trying to prime the pump and organize the effort against six priorities, eight different [Cross Functional Team] portfolios, and beneath that 31 signature systems.

You have to get the team focused on the right objectives and you have to lay in the financing over time, so as you get to various stages of maturity in that development process, you’ll have the money available. It started with the S&T [Science & Technology] portfolio, then, with the acquisition [funding]. We moved about 80 percent of S&T [funding]; we’re getting towards 60 percent of procurement.

But now prototypes are landing across the portfolios. We’re taking a PrSM [Precision Strike Missile] shot in November, an Extended Range Cannon Artillery shot in January. You’ll have LTAMDS [Lower-Tier Air & Missile Defense Sensor]. You have two demonstrators flying for Future Vertical Lift. Next Gen Squad Weapons — we’ll have that fielded by no later than ’22.

Explosion from the “arena” test of Lockheed’s Precision Strike Missile (PrSM) warhead.

So multiple systems are arriving. This will require us to get the ’20 to ’21 budget deal closed.

We’re working very hard. I was up on the Hill this morning [Tuesday] with all of the Army senior leadership at the Senate Army Caucus breakfast. We’re going to be back on the Hill again, early next week. We’re working with Congress to help them on all of their requests for information, to do everything we can to help get this budget deal closed.

It takes about a FYDP [i.e. a five-year Future Years Defense Plan] to get something done in development work; we are two years into that effort. The ’20 to ’21 deal is essential for us to realize our modernization strategy. Without it, it could potentially stall us out.

We have to get this budget deal.

Breaking Defense: And if there’s a year-long Continuing Resolution….

McCarthy: A year-long CR reduces the buying power of the Army by billions of dollars. It puts us in a very difficult position from a readiness standpoint. We reduce training: that’s rounds on the range, that’s hours of helicopter flight time, it’s miles of driving our vehicles. We will have soldiers less prepared than they can be, under continued resolution conditions.

From a modernization standpoint, no new starts [are allowed under a CR]: About 79 programs would be affected. An additional 37 programs that need production rate increases would not get them. [That’s at least 116 programs, a hair under the 118 program figure Gen. McConville cited this spring – the editors]

So we’re working very hard to get that bill.

A CH-47 lifts a Humvee

Breaking Defense: Congress is reinstating the CH-47F [helicopter, which the Army cut] and proposing major cuts to the Synthetic Training Environment.

McCarthy: Well, we had 186 major decision points in the ’20 [budget]: 93 truncated buys and 93 terminations. [Congress has supported] 185 of 186, so we feel pretty good about that. With respect to some cuts on certain portfolios, the program managers and CFT [modernization Cross Functional Team] directors were on the Hill last week and did a very thorough review with committees of jurisdiction, and we believe many of those have been restored.

A lot of this is just the effort required to communicate programmatic details to the committees of jurisdiction, and many cases they’re very supportive. There will be a couple that may not come in as proposed, but we’ll work our way through that.

Breaking Defense: But there are people on the Hill that are going, “the Army shuffled money around so fast, wait a minute, we want to do our proper oversight of this, and there are too many moving parts.”

McCarthy: I think they have every right to do that. It just requires a lot more energy for us to cross the river and communicate the changes. And when you do that, we find very receptive members and staff who work with us to get those outcomes.

Breaking Defense: How about the industrial base? You can have some cases where you have very enthusiastic response, like the five competitors for Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft designs. Other places like the Optionally Manned Combat Vehicle, which has just one bidder, there’s a less enthusiastic response.

Textron execs pose with their Ripsaw Robotic Combat Vehicle-Medium proposal at AUSA 2019. Left to right: CEO Lisa Atherton, Geoff Howe & Mike Howe of Textron’s Howe & Howe robotics subsidiary, and David Ray of FLIR.

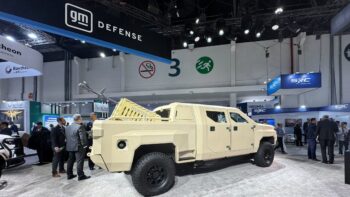

McCarthy: This is my third AUSA serving in this hallway [i.e. as Under Secretary, Acting Secretary, or Secretary of the Army.] And what I noticed, and what Gen. McConville noticed, and Mr. McPherson, and Gen. Murray and all the Army senior leaders — what we saw was a vast increase in prototypes and demonstration model capabilities from the defense industry, in alignment with the Army investment portfolios.

On Long-Range Precision Fires, we’re very encouraged by what we see.

On the [OMFV] combat vehicle, there’s been a lot of back and forth, we are evaluating opportunities, so I don’t want to elaborate too much there. We need a few more weeks before they look at good samples to see where we’re at.

On Future Vertical Lift, industry’s investing four dollars to one [from the government], so clearly, there’s appetite and desire to pursue that.

The network is incredibly complex portfolio, a lot of different capabilities were put forward.

Missile defense, we’re tracking well with the IM-SHORAD and LTAMDS.

And then on Soldier Lethality, we have three capabilities [ENVG-B, IVAS, and NGSW] that will probably arrive in the formation the soonest of all of these capabilities here.

Overall, I will tell you Army senior leadership was encouraged because the vendors understand the investments. They’re stepping forward, opening their own checkbooks, they’ve increased [Independent Research And Development] dollars well above inflation – if you went over two years ago, it was below inflation.

Stryker anti-aircraft variant, IM-SHORAD (Interim Maneuver Short-Range Air Defense)

We’re very encouraged, but again, we need to deliver this ’20 to ’21 deal, or all of that good will and energy will stall out.

Breaking Defense: We’ve talked about Congress and the budget, we’ve talked about industry, but the feet the Army has historically tripped over since 1999 have been its own.

McCarthy: I think where we are different is the really considerable amount of funding over and above historic norms on prototypes and in experimentation. We expended enormous amount of energy to get that through OSD and then over to Congress.

We want to test these capabilities and really wring out the requirements, see what’s available, so that we don’t go down the path of the catastrophic failures of past weapons systems where you lose billions of dollars and you harvest next to nothing in capabilities. The very robust prototyping and experimentation program is to reduce that risk and see a tangible practical outcome right there in front of your face.

Breaking Defense: But some of this is not going to work. There is the whole “fail early” idea, which sounds great in theory until you have to come back to Congress and say, “this thing we did didn’t work.” How do you make the case that this failure is not a failure of the program, it is a learning experience to get to the ultimate success of the program?

Under Secretary Ryan McCarthy gets briefed on new sensors for the 8×8 Stryker vehicle

McCarthy: I’ve taken particular interest in getting down to units and see that unit testing the system. [We tell soldiers], ‘write down everything you see, capture as much of the information as you can from these tests, because we’re going to learn from the test.’

[Even if the test fails], it might be able to harvest something and then turn that into an adjusted prototype on the next evolution. The key is learning from the experiences. But if you don’t do well on the test, and it’s a catastrophic failure, you have to have the courage to walk away.

Breaking Defense: So, if this works, how do we launch into the next phase of the 16-year plan. How the heck can you predict 16 years out in the future?

McCarthy: To quote my old boss Robert Gates, “America has a perfect record of predicting incorrectly.” You don’t want to try to predict what the next war is.

But if you have capabilities that perform in the prototype, and you’re positioned to scale them up quickly, then the Army senior leaders will have to make choices, because there’s just so many units, you’re going to have only so much money. We’ll have to be very stern in our prioritization and make some difficult choices.

Denmark to pass 3 percent GDP on defense over fear of Russian rearmament

European powers are still struggling to come to terms with the reality of urgently having to do more to protect the continent without relying on the US for renewed support.