Prototype Stryker anti-aircraft variant, IM-SHORAD (Interim Maneuver Short-Range Air Defense)

ARLINGTON: One of the savviest — and snarkiest — veterans of the Army acquisition system is warning her former colleagues that not all 31 of the service’s priority programs will survive.

“You’ve got to prioritize your top 31 choices, because you can’t have them all,” said former assistant secretary Heidi Shyu. “It’s like going through the buffet table and you have 31 courses.”

Heidi Shyu

As the Army’s top buyer from 2011 through 2015 — when the cash-strapped service repeatedly scrapped new weapons programs to fund upgrades to old ones — Heidi Shyu compared the acquisition bureaucracy to a bus where every passenger has his own steering wheel and a brake. Speaking here last week to the Association of the US Army, she added an update: You don’t want to give everyone their own gas pedal, either.

The Army has reallocated $33 billion over five years to kick-start 31 high-priority programs (grouped in six categories), many of which are now rushing into rapid prototyping. That step is absolutely necessary, but hardly sufficient.

“There’s a huge gap between a prototype and a program of record that’s production-ready, ready to transition into production, and I would warn you that I don’t hear about that aspect,” Shyu said. “My biggest concern is that when the budget goes down — that’s only a matter of time — that, one, we’re left with a bunch of prototypes but nothing in inventory, and a bunch of legacy systems without upgrades; and two, when the prototypes finally turn into production-ready weapons systems, how can the Army afford so many big-ticket procurement bills simultaneously?”

A successful prototype proves that the weapon works. It does not prove it can be affordably and reliably manufactured, maintained and sustained for years. When you prioritize a new technology, warned retired Lt. Gen. Thomas Spoehr, you need to put a similarly high priority on the maintenance and logistics to keep it operational.

There’s a lot to get right, across a lot of programs. “It would defy the odds that every one of those 31 programs was appropriately conceptualized, the requirements were right, the funding was right, the employment concepts were right,” he told the AUSA conference. “It’s almost certain one will fail, or one will be terminated maybe even soon.”

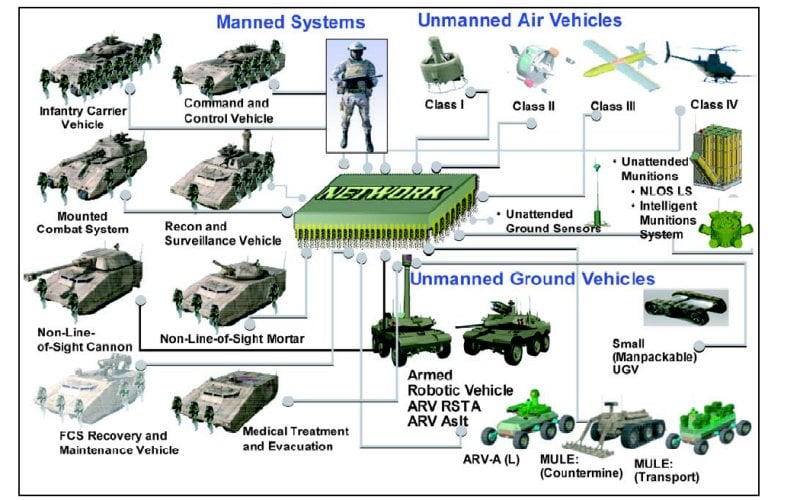

The Army’s salute-and-shut-up culture often causes officers and officials to insist that something working, or can be made to work, rather than warning that it’s off the rails, Spoehr said, as on cancelled Future Combat System and Ground Combat Vehicle. Now the four-star chief of the year-old Army Futures Command, Gen. John “Mike” Murray, is waging an uphill battle to change that culture.

Army slide showing the elements of the (later canceled) Future Combat System

“Gen, Murray talked about this in an article that Sydney wrote in Breaking Defense. [He] said that ‘failure is an option,’” Spoehr said. “How we react to that failure will be defining. Do we do like we have sometimes done in the past, try to put patches on the program, try to modify the PowerPoint charts to make it look like it’s not failing, or do we cut bait… getting as much of our money out as we can … before OSD takes that money?”

The Army Replies

The Army’s high-speed prototyping programs aren’t short-circuiting essential steps, service officials replied.

“All these things are happening simultaneously. We’re not skipping steps,” said Brig. Gen. John Rafferty, modernization director for long-range weapons. “We know we’re going to have to transition things to traditional programs.

“To Ms. Shyu’s point earlier about, have we thought through things? The answer is yes— but that doesn’t mean we have the plan yet,” he said.

Then-Col. John Rafferty teaches field artillery operations in Tajikistan.

“We are balancing exactly what Ms. Shyu talked about earlier today,” said Darryl Colvin, the deputy Program Executive Office for Missiles & Space. “How do you ensure that you’ve addressed the ‘ilities’” – like affordability, manufacturability, reliablity – “to get to a production-representative design?”

Consider the Army’s urgent effort to field new frontline anti-aircraft/counter-drone vehicles, what’s called Interim Maneuver Short-Range Air Defense. It took 19 months, instead of the usual five-plus years, to go from a first draft of the official requirement to getting multiple prototypes in testing.

“We have five prototypes that have been delivered, today,” Colvin said. “In testing … for both hardware and software… we make the changes on the spot, update the design and we move on.”

“Yes, there’s some risk associated with that, we realize that,” he acknowledged, but it’s necessary to fill a major gap in the Army’s defenses.

Rafferty’s team also sees prototypes as a way to work out the bugs before production. “We’re very close to delivering the first Extended Range Cannon Artillery system prototype” – an upgraded Paladin howitzer – “to Yuma Proving Grounds,” he said. But even before the first prototype is delivered, he said, veteran NCOs from the Army’s artillery school at Fort Sill will check it out and recommend fixes to implement on the next prototype: “We’re going to have cannoneers crawling all over it, so Prototype 2 will be better than Prototype 1.”

Instead of taking one step at a time, Rafferty said, the Army will test multiple components of the ERCA cannon – the vehicle, the projectiles, the fuses – in parallel. Likewise, he told me in a later interview, his team jumped immediately from ground tests of the new Precision Strike Missile to a flight test of a prototype, complete with live warhead, rather than staging one test to prove it could launch, another to prove it to fly, and another to finally strike a target. Meanwhile, he said, for both ERCA and PrSM, the Army has avoided locking down the final, formal requirements, so it keep adjusting them based on input from testers and soldiers.

Is all this enough to address Shyu and Spoehr’s concerns? Maybe. It’s definitely valuable to get lots of early input from contractors, testers, and users on what works and what doesn’t. It can prevent a host of potential problems. But there are other problems that might not show up without systematic, exhaustive and step-by-step testing and analysis — and that takes time.

Army 30-Plus Priorities – R… by BreakingDefense on Scribd

Taking aim: Army leaders ponder mix of precision munitions vs conventional

Three four-star US Army generals this week weighed in with their opinions about finding the right balance between conventional and high-tech munitions – but the answers aren’t easy.